Türkiye’s strategic relevance has grown substantially. Its trajectory reflects many of the central dynamics identified in the Institute for Economics & Peace’s report The Great Fragmentation: The Rise of Middle Powers in a Fractured International Order – a world in which power is dispersing away from superpowers and toward a widening group of influential middle states.

The report finds that global influence is no longer concentrated among a small number of dominant actors. While the United States and China remain the world’s most powerful nations, their ability to shape outcomes unilaterally has plateaued. In contrast, middle powers have expanded their collective economic capacity, diplomatic reach and regional influence. These countries are not replacing great powers, but they are increasingly determining how geopolitical competition, cooperation and conflict unfold.

Türkiye stands among the most prominent of this group. Its influence extends well beyond its economic size, driven by a combination of geography, military capability, diplomatic activism and strategic autonomy. Unlike traditional allies embedded firmly within one geopolitical camp, Türkiye has pursued a more flexible and transactional approach to foreign policy, one that has become increasingly characteristic of middle powers operating in a fragmented international system.

Economically, Türkiye ranks among the world’s largest emerging economies, with deep trade links to Europe, Asia and the Middle East. Its customs union with the European Union, extensive manufacturing base, and role as a regional energy transit hub provide it with enduring structural importance. At the same time, Türkiye’s geographic position gives it leverage over critical infrastructure and trade routes, from energy pipelines connecting the Caspian region to Europe, to maritime access through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits.

In a fragmenting global economy, such chokepoints matter. As The Great Fragmentation highlights, influence today increasingly flows through connectivity via trade corridors, logistics routes, energy systems and supply chains, rather than purely through economic scale. Türkiye’s location allows it to shape flows between regions at a time when global integration is becoming more politicised and less predictable.

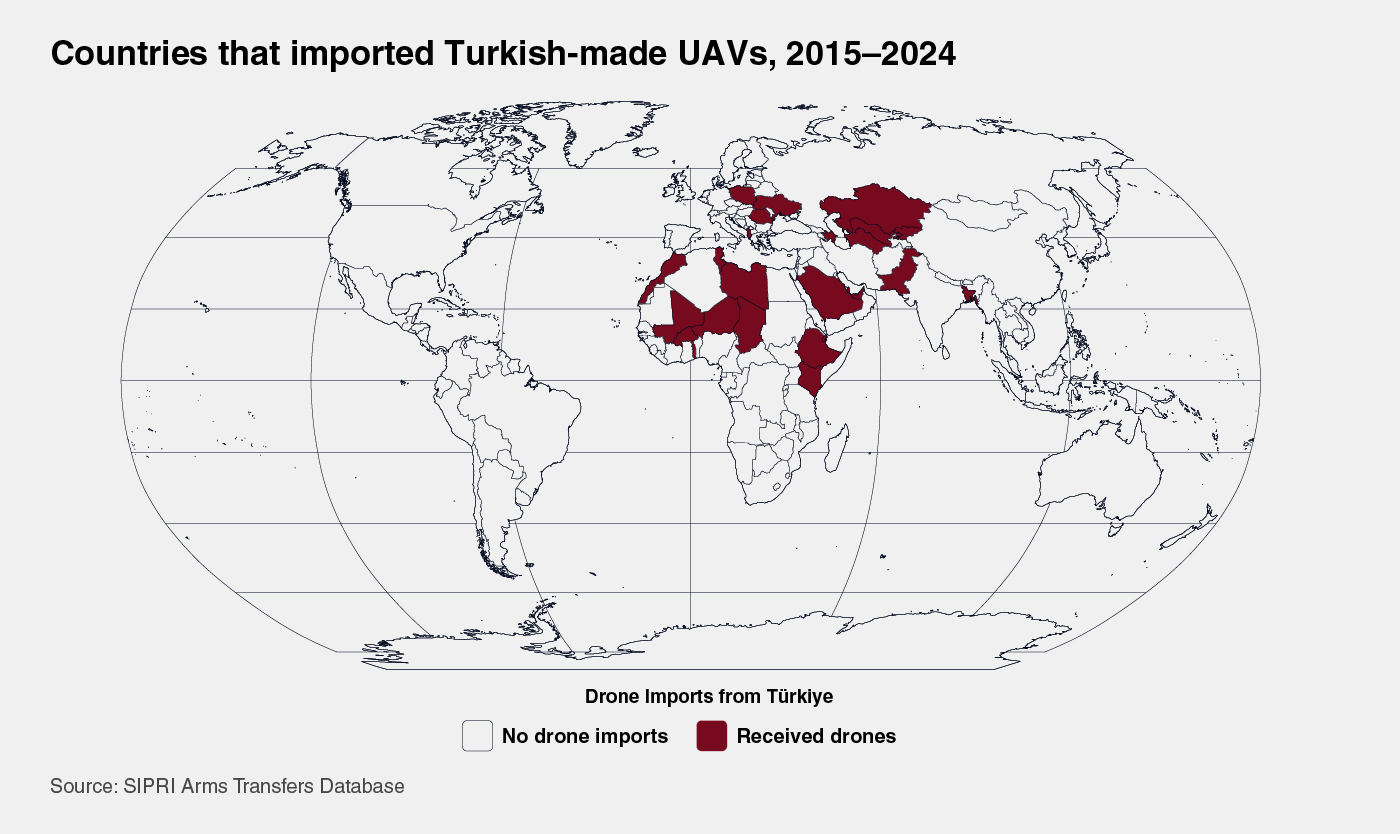

This strategic positioning has been reinforced by Türkiye’s expanding military capacity. Over the past decade, it has invested heavily in domestic defence production, particularly in drones, armoured vehicles and naval capabilities. These investments have not only strengthened national defence but also enabled Türkiye to project influence abroad through security partnerships and arms exports.

The use of Turkish-made drones in conflicts from Ukraine to the South Caucasus has elevated Türkiye’s profile as a defence actor, demonstrating how middle powers can convert technological capability into geopolitical relevance. As the report observes, middle powers are increasingly building independent material capacity rather than relying solely on traditional security guarantees from great powers.

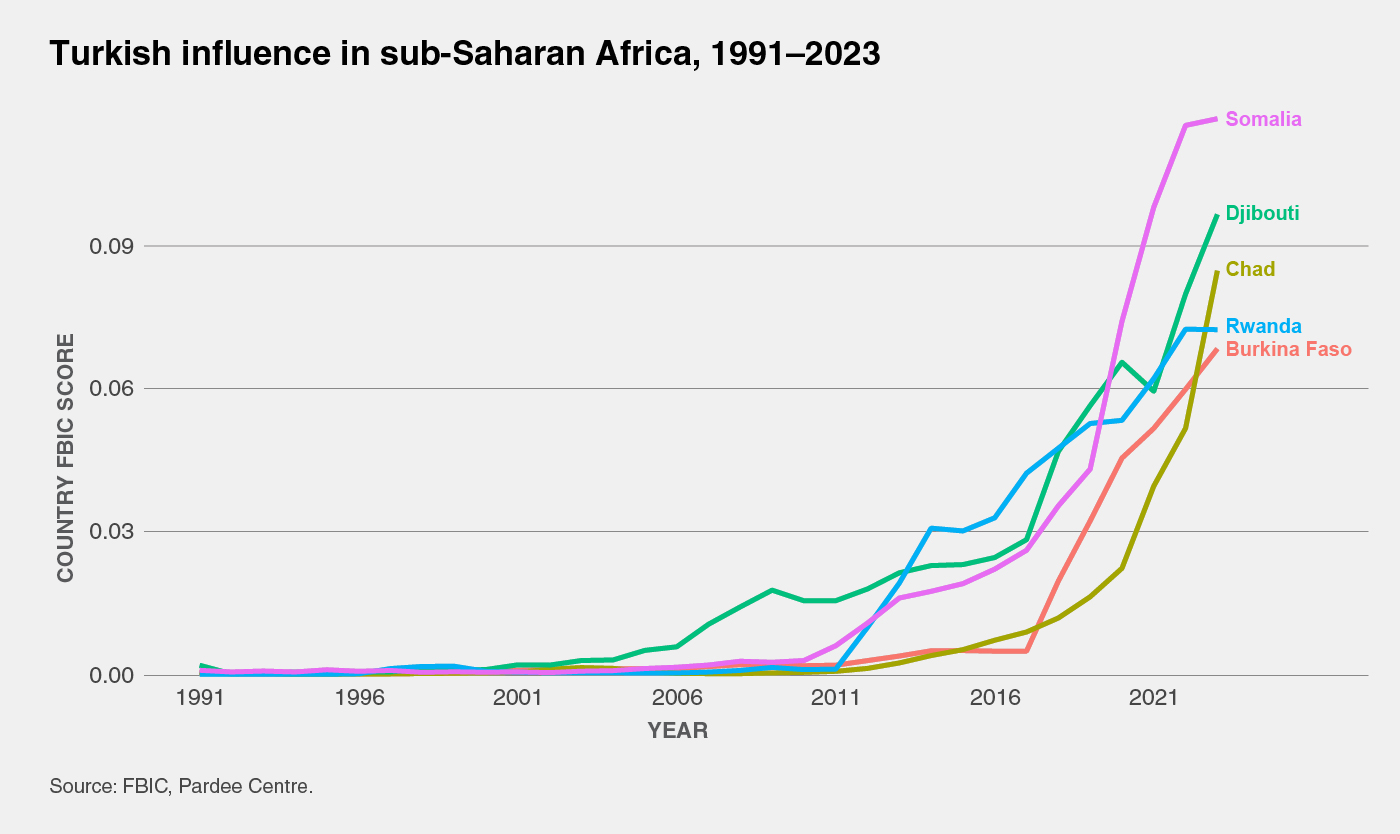

Türkiye’s foreign policy reflects a deliberate pursuit of strategic autonomy. While it remains a member of NATO, its relationships extend far beyond the alliance. Ankara has maintained engagement with Russia, deepened ties with Gulf states, expanded its footprint in Africa, and pursued active diplomacy across Central Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean. This multidirectional approach often places Türkiye at odds with traditional partners, yet it also exemplifies the hedging behaviour increasingly common among middle powers.

Rather than committing fully to one geopolitical bloc, Türkiye seeks flexibility, maximising room for manoeuvre in a system where rigid alignment can constrain national interests. This approach aligns closely with one of the report’s central findings: in a fragmented order, influence accrues to states able to operate across multiple diplomatic networks simultaneously.

Türkiye’s role in the war in Ukraine illustrates this dynamic. Ankara has provided military support to Ukraine while maintaining diplomatic channels with Russia, including facilitating grain export agreements through the Black Sea. This dual engagement has drawn criticism from some partners, yet it has also enabled Türkiye to act as an intermediary at moments when few others could. In a polarised international environment, such brokerage roles are becoming increasingly valuable.

This capacity to mediate reflects a broader shift in global diplomacy. As trust between major powers erodes, neutral or semi-aligned states are often better positioned to facilitate dialogue. The Great Fragmentation identifies this as one of the emerging functions of middle powers: not as arbiters of global order, but as pragmatic problem-solvers within specific regions or issues.

Türkiye’s regional security footprint has expanded significantly over the past decade. It maintains military bases or installations in Northern Cyprus, Qatar and Somalia, operates across northern Syria and Iraq, and plays an active role in the South Caucasus. These engagements reflect a more assertive posture than in previous decades, driven by security concerns, regional ambitions and a desire to shape outcomes near its borders.

At the same time, this activism carries risks. Operating across multiple conflict zones exposes Türkiye to entanglement, economic strain and diplomatic friction. The Global Peace Index has consistently shown that higher external conflict involvement is associated with declining peacefulness. For middle powers, expanding influence often brings increased exposure to instability.

Domestic dynamics further shape Türkiye’s position in the fragmented order. Political polarisation, economic volatility and inflationary pressures have created internal challenges that interact with external ambitions. The IEP framework emphasises that sustainable influence depends not only on external projection but also on internal resilience – social cohesion, institutional strength and economic stability.

Domestic unrest can quickly translate into geopolitical vulnerability, which reinforces the importance of maintaining the internal foundations of peace. Middle powers with strong material capacity but fragile internal conditions may find their influence difficult to sustain over time.

Despite these challenges, Türkiye’s role in the international system continues to expand. Its engagement across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia reflects a confidence in operating independently of traditional power centres. This reflects a wider trend identified in The Great Fragmentation: as global governance becomes less centralised, states with the capacity to act autonomously gain disproportionate influence.

The weakening of multilateral institutions has further elevated Türkiye’s importance. As global forums struggle to deliver consensus, regional and minilateral arrangements have become more prominent. Türkiye has increasingly operated through these flexible formats, whether in energy diplomacy, security cooperation or regional development initiatives.

This shift does not imply the disappearance of global institutions, but rather a diversification of governance. In such an environment, middle powers serve as connective tissue, linking regions, mediating disputes and sustaining functional cooperation where formal mechanisms fall short.

Türkiye faces a complex strategic landscape. Its geographic advantages and diplomatic reach provide significant opportunity, yet intensifying great-power competition and regional instability also constrain its choices. Managing relations with both Western partners and non-Western powers will require continued balancing, adaptability and restraint.

Climate risks, energy transitions and economic fragmentation will further shape Türkiye’s trajectory. As supply chains regionalise and energy security becomes more politicised, Türkiye’s position as a transit hub and manufacturing centre could strengthen, provided domestic economic stability is maintained.

Türkiye’s experience exemplifies the world described in The Great Fragmentation. Power is no longer defined solely by size or alignment, but by the ability to navigate complexity. Middle powers are not shaping global order through dominance, but through economic, diplomatic and strategic presence across multiple arenas. In this emerging system, Türkiye is neither fully aligned nor isolated. It is an active participant in a fractured landscape, pursuing autonomy while managing interdependence. Its choices, like those of other rising middle powers, increasingly influence regional stability and global outcomes.

Further reading: