With many countries around the world relying on large, shared rivers, there is increasing risk that poor management of these shared resources could lead to conflict.

Water risk is one of the most significant ecological threats the world is currently facing. Two billion people globally live in areas that lack access to safe drinking water while 3.6 billion lack access to safe sanitation. Water stress impedes economic development and food production, which further compromises the health and well-being of the population. It can also lead to social tension, conflict and displacement.

The 2023 Ecological Threat Report produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace identifies some water hot spots, along with a cost-effective water capture solution.

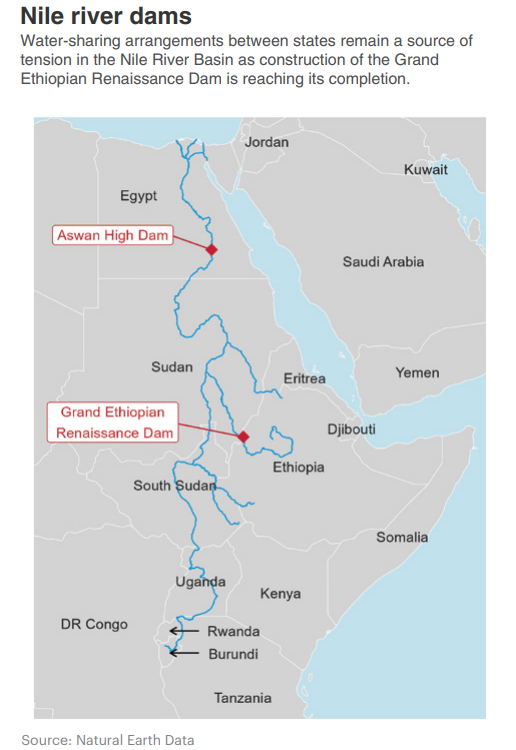

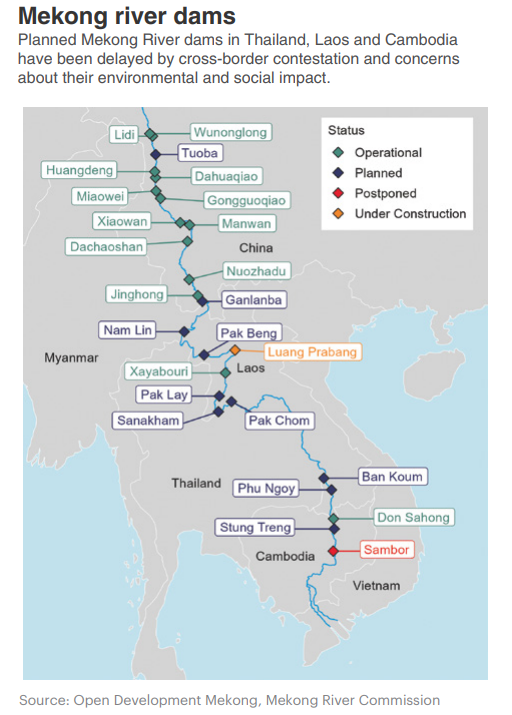

The Nile delta and Mekong River systems pose significant challenges and contain nearly half a billion people between them.

Egypt is highly reliant on its historical 85 per cent allocation of Nile water to support its growing population of over 100 million. So is Ethiopia, which has almost completed the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) to fuel its economic growth.

The risk of violent conflict involving Egypt and Ethiopia has been considered high in recent years.

The GERD was completed in September but broader water sharing arrangements are yet to be resolved. Sudan, previously an opponent of the dam, is now in favour of the project as it hopes the GERD will aid management of Nile flooding.

While the likelihood of armed attacks from Egypt is low, as destruction of the dam would result in catastrophic levels of ecological damage, it remains a key source of tension between countries in the region.

Another example is the construction of dams on the Mekong. Six countries share the Mekong River in Southeast Asia, which begins in China. Over 360 million people depend on the Mekong River, including for energy generated by hydroelectric dams.

Building dams has required moving communities, and there are major concerns about their environmental and social effects. Cambodia had paused some dam projects because of these concerns but restarted one in 2022. Dam plans near the Thai-Laos border face opposition from neighbouring countries, locals, and NGOs.

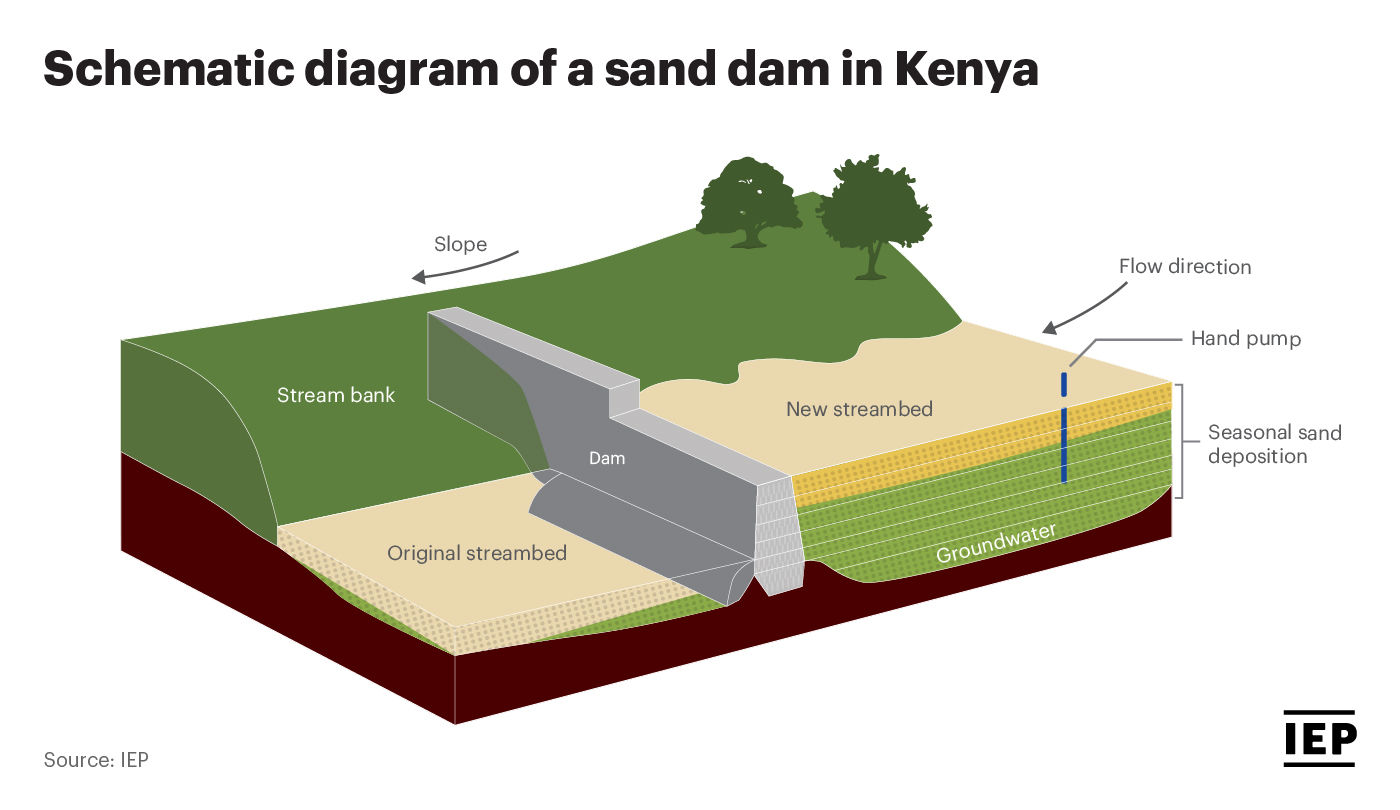

One cost effective method of water capture is sand dams.

Abstraction of water from sandy seasonal riverbeds is an ancient practise where natural dikes capture the water stored in the sand.

Subsurface dams and sand dams are artificial enhancements to natural dikes, which if constructed carefully last for an exceptionally long period of 50 to 100 years.

A sand dam is a dam built in a seasonal dry riverbed onto bedrock or an impermeable layer. It is constructed across the river channel to block the subsurface flow of water through the sand.

The upstream reservoir of such a dam can be composed of 40 per cent water when made up of coarse sand. The water can then be retrieved for multiple uses including domestic purposes, livestock and irrigation.

The captured water also seeps into the banks of the river increasing the vegetation and biodiversity. The cost to build one of these dams is approximately $50,000.

A very large sand dam can hold 71,000 cubic metres of water (71 million litres) which when amortised over 10 years will yield water for 29 cents per thousand litres. Large dams can yield 400 tonnes of produce.

Based on World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates, this is enough for 2,790 people’s fruit and vegetable requirements.

A study done on sand dams in Kenya estimates the value of 400 tons of produce to be around 20 million shillings ($180,000). The return on investment will vary depending on the crops and price of staples at the time.

The Charitable Foundation has conducted a detailed feasibility study which showed that in many locations, little or no agriculture was being undertaken before the installation of the sand dam. Subsequent agricultural activity has been central to uplifting the regions.

TCF has built 30 sand dams in Kenya and is exploring ways of scaling the benefits through establishing the business case for investing in the construction of sand dams.

Other water projects include:

Dispensers for safe water in Zomba, Malawi. This project was developed by Evidence Action to install chlorination dispensers at water collection points, making the water safe enough to reduce the need to boil. This was then recognised as a carbon emission reduction program, obtaining carbon credits, and monetised to help finance the maintenance of dispensers and refilling them with chlorine.

Sustainable water sourcing through engineered Wetlands. A community-based initiative in the Chinese villages of Xiadong and Lixi in the Dongjiang River Basin developed a project with Conservation International funding to make their water system more sustainable. The communities constructed a water treatment system that mimics wetlands.

Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration is a low-cost land restoration technique developed by Tony Rinaudo from World Vision. FMNR promotes water harvesting techniques as the planting includes a micro-catchment which traps surface run-off, makes the soil and water settle down, and feeds the plant at a microsite.

Countries facing resource scarcity have lower coping capacities to manage resource scarcity shocks. These countries also tend to have unsustainable population growth, low or volatile economic growth, high rates of poverty, lack of societal resilience and greater prevalence of food insecurity. With this in mind, there is a clear need for building more resilient and sustainable food and water systems in communities vulnerable to resource scarcity.