At the upcoming annual international climate summit, COP28, convened by the UN in Dubai in early December, countries, climate advocates and industry stakeholders will resume efforts to achieve consensus on how the world should be responding and adapting to climate changes, including heatwaves, storms and rising sea levels.

The key finding from the 2023 Ecological Threat Report (ETR), produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace, is that without concerted international action, current levels of ecological degradation will substantially worsen, intensifying a range of social issues, such as malnutrition and forced migration. Current conflicts will escalate and multiply as a result, creating further global insecurity.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres cautioned in July that the era of global boiling had commenced. He highlighted that rising temperatures had already caused significant damage and urged leaders to take action to prevent further increases in the number of catastrophic disasters.

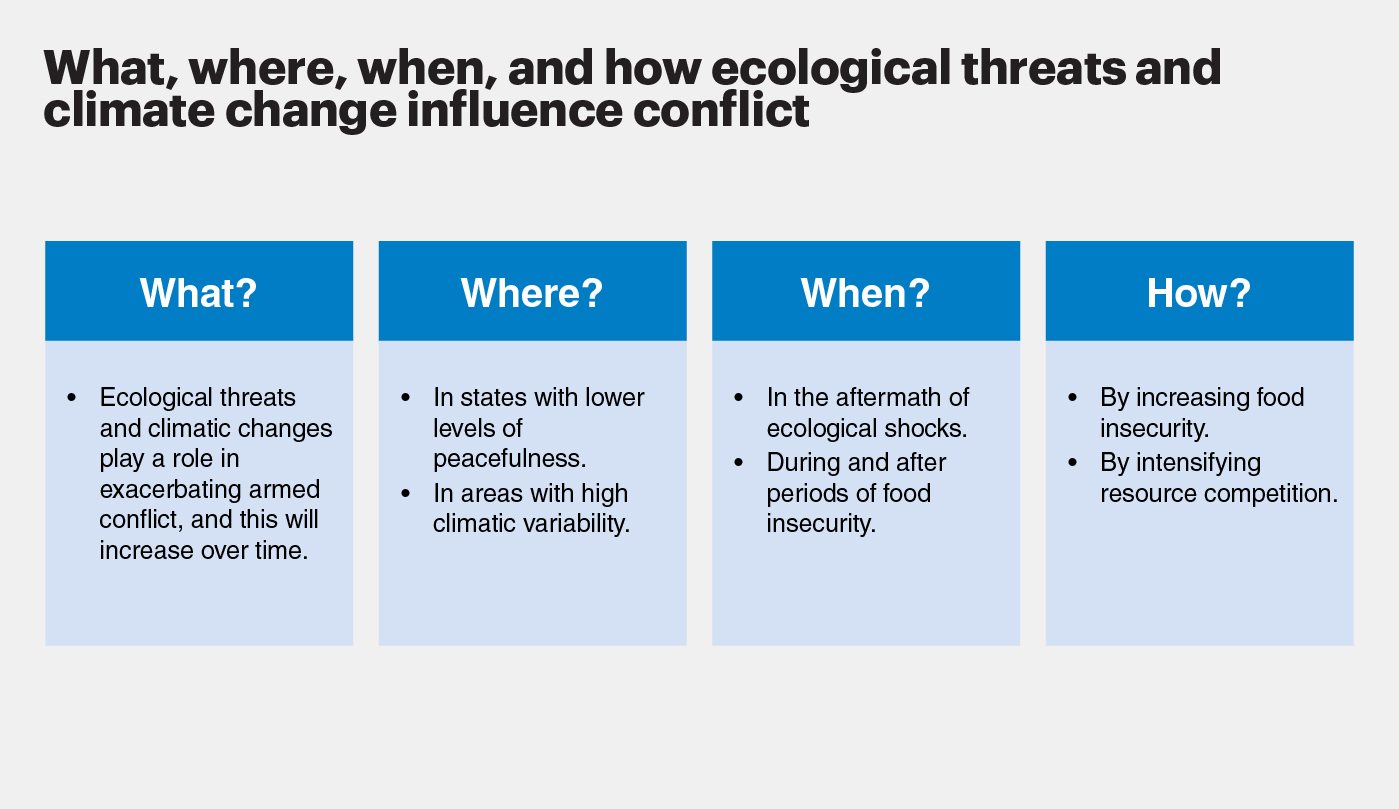

Climatic changes, whether naturally occurring or human induced, have been linked to changes in conflict dynamics in almost all forms of human discord.

A relationship between climate and conflict can be found in data covering the past 10,000 years. For example, severe droughts are associated with the collapses of the Mayan and Angkor empires and dynastic changes in China, while severe cold is associated with instability in Europe during the 17th century.

It can be reliably linked to conflicts or violence in every region, as well as in global trends.

The research measuring the direct impact of human induced climate change on armed conflict is still in its infancy. While there is uncertainty on the effect to date, there is agreement that it is likely to accelerate in coming decades.

The ETR quantifies that for an average increase of one degree in temperature there is a 13 per cent associated increase in intergroup conflict.

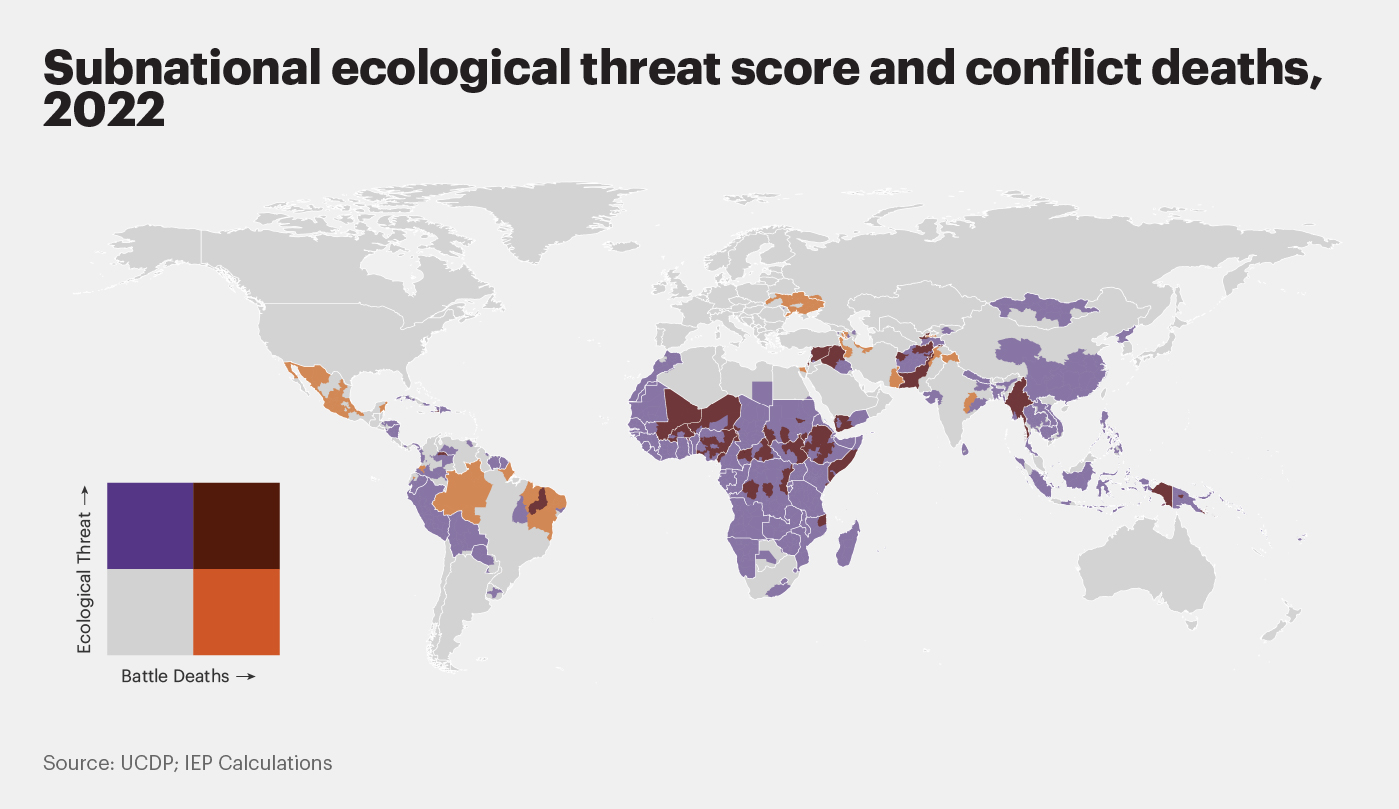

Past conflict is usually the best indicator of future conflict. Areas already prone to conflict are most at risk, and ongoing conflicts may worsen due to climate change.

Regions that are more dependent on agriculture are also more likely to be affected, in particular areas with high levels of subsistence farming. Transition zones, like the Sahel, are particularly prone to conflict.

Permanently harsh climatic zones are less likely to experience conflict compared to these transitional zones which experience more variability and are more prone to precipitation shocks affecting important agricultural zones.

Vulnerability to conflict from ecological shocks is not uniform across different countries and regions. Countries with large populations, low societal resilience and lower levels of development experience higher conflict risk from climate related disasters.

Within countries, areas with a history of resource-competition-based conflict like Karamoja in Northeastern Uganda are becoming more prone to climate-linked conflicts. These risks are present even with sustained efforts to create peace between different groups.

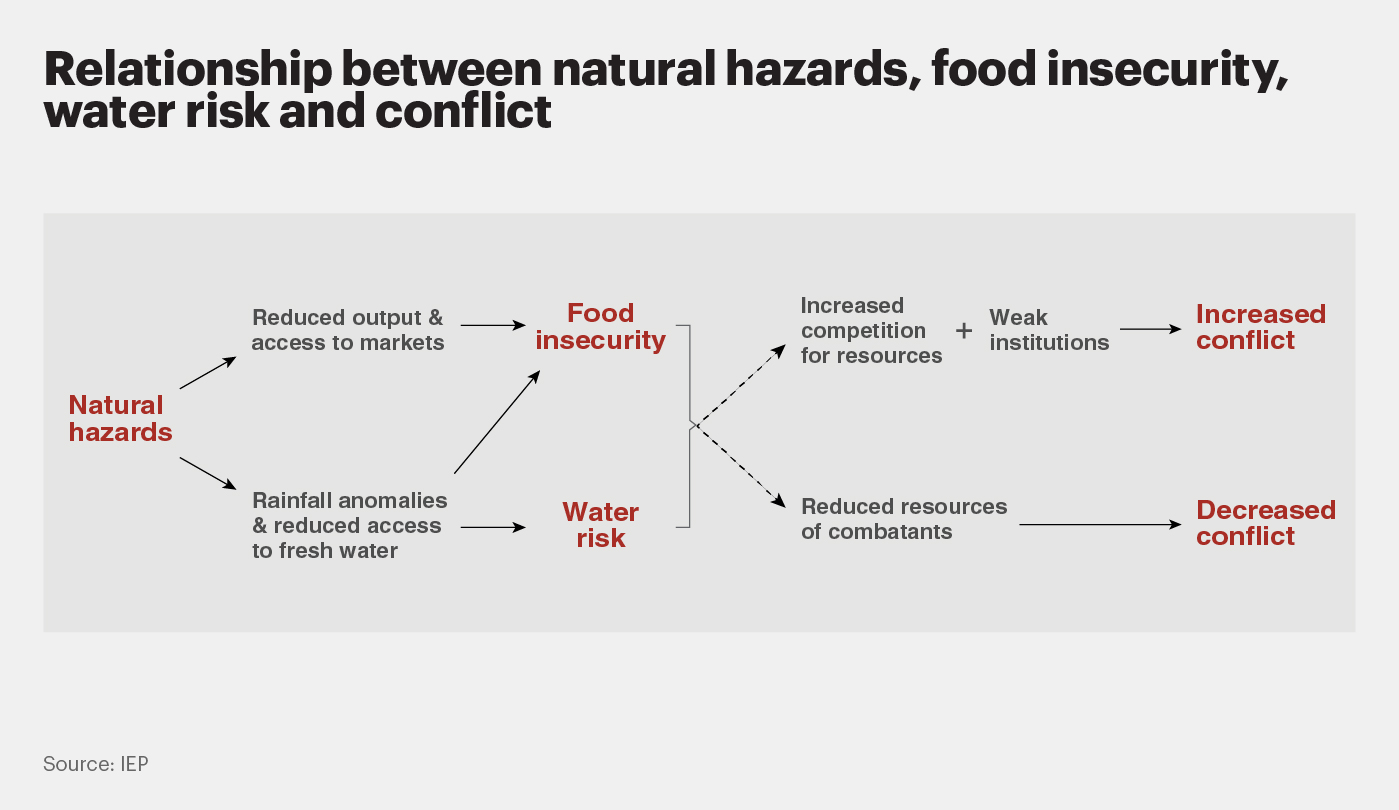

Ecological shocks that damage livelihoods can increase opportunities for armed extremist groups to recruit new members.

Shifts in ETR scores are associated with increased risk of conflict. A shift in indicator score of 25 per cent for food insecurity, natural disasters, and water risk increases the risk of conflict by 36 per cent, 21 per cent, and 18 per cent respectively.

Conflict over goods from the global commons like fisheries is increasingly common as demand increases and effects of climate change affect ocean ecology. This is particularly acute during climatic extremes like El Nino events.

Interstate conflict becomes more likely following rising temperatures or rainfall shocks, especially where states stand to lose from existing agreements on water sharing.

The impact of climate change on conflict can be overstated compared to the impact of political instability.

For example, recent analysis of Lake Chad, has argued that political mismanagement of water resources has played the bigger role in fueling conflict. In sub-Saharan Africa, flooding is linked to increased communal violence in administrative districts where there is a lack of trust in local institutions.

Ecological threats have the biggest impact on conflict in regions like the Sahel, which face major deficiencies in governance and rule of law, high levels of poverty and short-term climatic variations.

There is a reduced risk of intercommunal violence in the aftermath of flood disasters where local government councils and judicial courts are trusted.

Download the Ecological Threat Report 2023

Ecological Threat Report 2023