In this year’s Mexico Peace Index 2025 report, we examined violence against women in Mexico, highlighting how it is deeply rooted in machismo, impunity and socio-cultural norms that perpetuate discrimination against women. Impunity and ineffective institutional responses represent a critical challenge for preventing and punishing gender-based violence in Mexico.

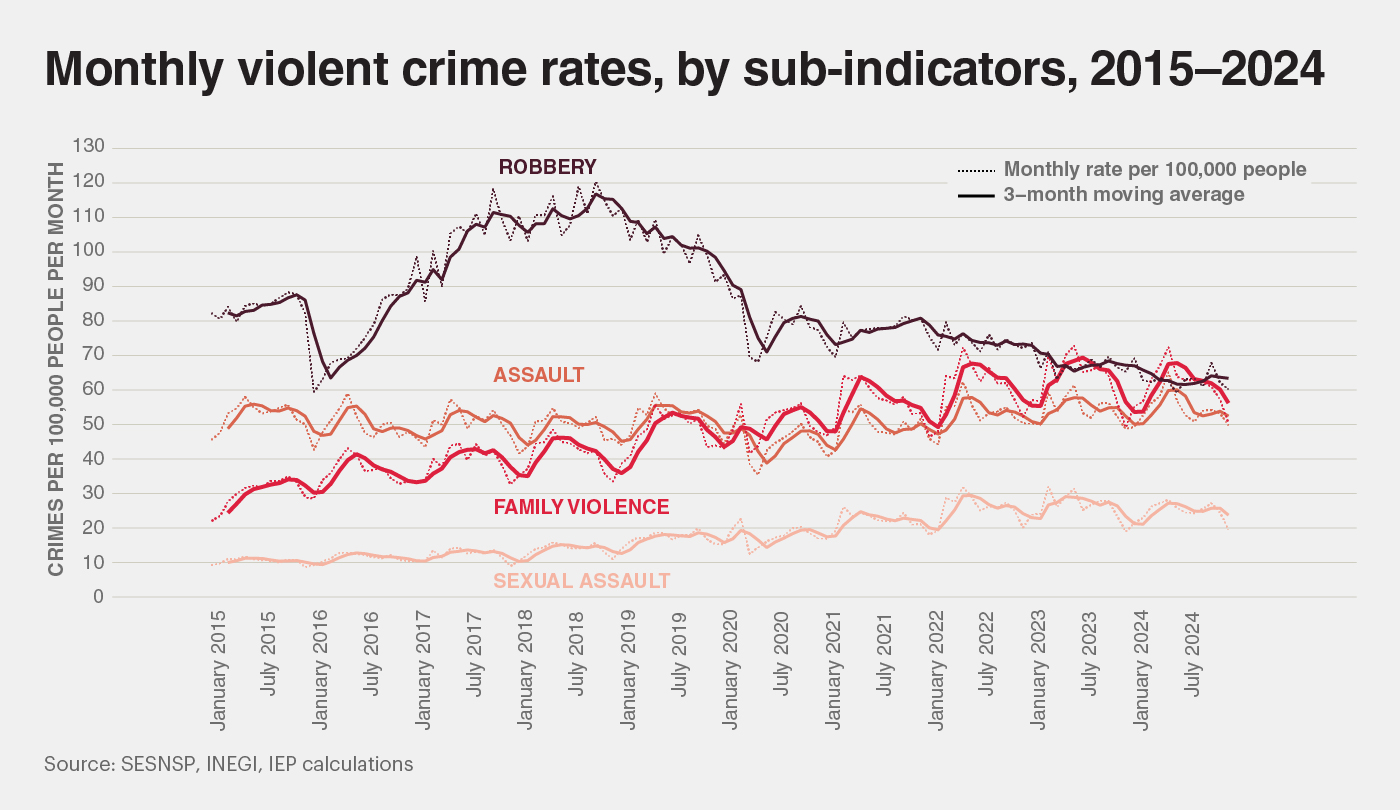

The two violent crime sub-indicators of the Mexico Peace Index most associated with violence against women are sexual assault and family violence. The official rates of these two sub-indicators have more than doubled in the past decade, as reflected in the following figure. Moreover, the state of Colima has experienced the worst deteriorations in both. Colima’s rate of sexual assault has increased tenfold since 2015, and its rate of family violence has increased fivefold.

However, it is difficult to know to what degree the changes in national and state-level rates may be affected by heightened awareness resulting in these crimes being reported more frequently. Historically, reporting rates for gender-based violence in Mexico have been extremely low. Recent estimates suggest that about 93 per cent of sexual violence cases go unreported, or do not result in an investigation. Many victims do not even file complaints, owing to factors such as fear of retaliation and distrust in authorities. In addition to perceptions of inefficiency or indifference from institutions, documented cases have shown that gender prejudices within law enforcement and prosecutors’ offices can obstruct access to justice by shifting blame onto victims instead of holding aggressors accountable.

National survey data indicates that for every sexual offense committed against a man, nine are committed against women. Moreover, seven in ten women over the age of 15 report experiencing some form of violence in their lifetimes, including 39.9 per cent who had suffered abuse from a partner. Half of women aged 15 and older reported experiencing sexual violence at some point in their lives, and 23.3 per cent in the 12 months prior to the survey. Young girls are also disproportionately victimised by these types of crimes, with girls between the ages of five and nine being three times more likely to be sexually abused than boys, while girls between 15 and 17 years old are abused eight times more often than boys of the same age.

A rising form of violence against women, especially adolescents, is cyber harassment. Like many forms of violence in Mexico, cyber harassment is underreported. Between January 2022 and May 2023, only 2,515 cases of digital or cyber violence were officially reported in the country, with the overwhelming majority of victims being adolescents and young adults. According to the 2021 Cyberbullying Module (MOCIBA) of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), 22.8 per cent of women over the age of 12 experienced some form of cyber harassment in the year prior to the survey, affecting approximately 9.7 million women. Moreover, 33.6 per cent of girls and adolescents aged 12 to 17 have reported receiving disturbing sexual photos or videos, while 32.3 per cent have experienced unsolicited sexual advances online. The most common forms of cyber harassment include contact from fake identities, offensive messages, unsolicited sexual content and unwanted sexual propositions.

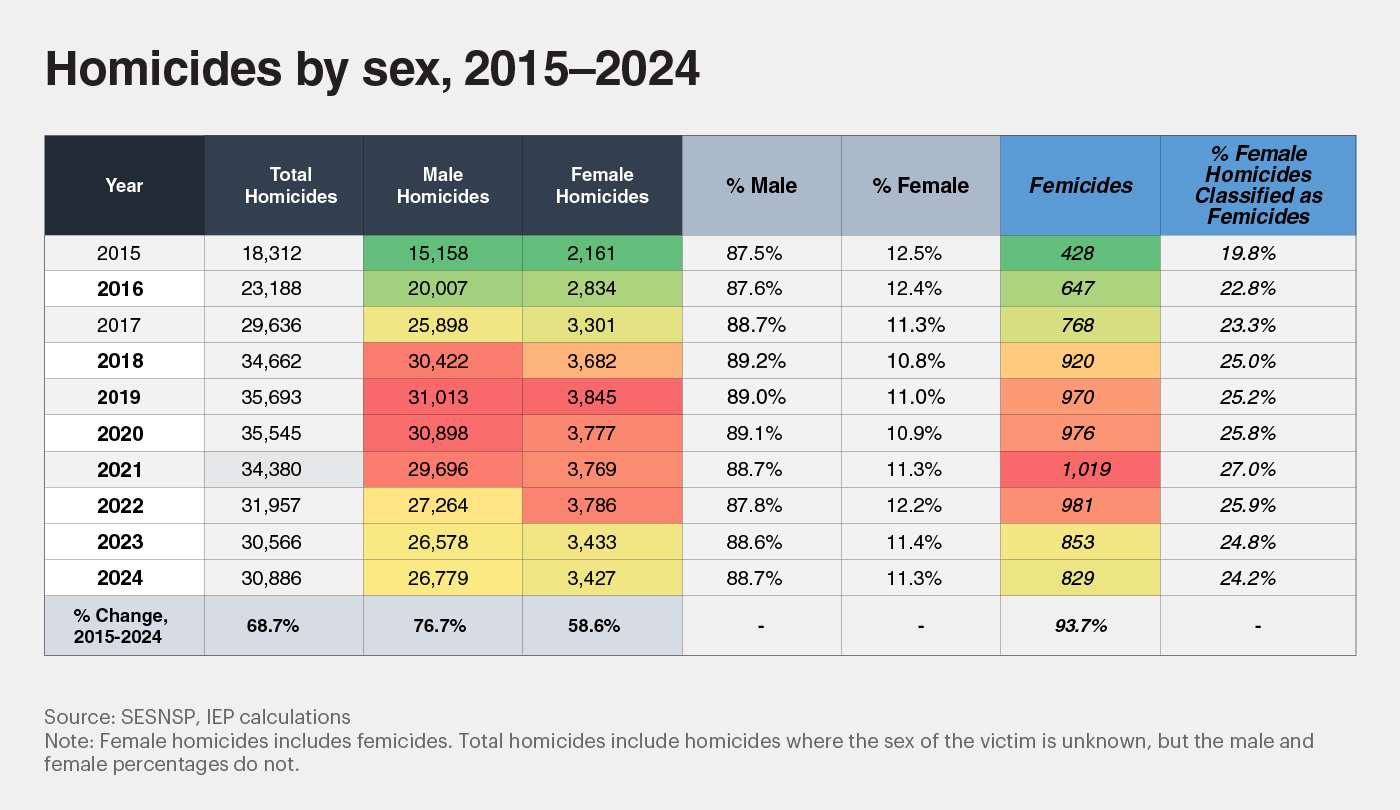

In extreme cases, gender-based violence against women results in murder, a crime known as femicide. Femicides have become a major concern in Mexico as recorded cases have risen significantly in the past decade. In 2015, femicides represented 19.8 per cent of female homicides, however this proportion had increased to 24.2 per cent by 2024.

While femicides are usually included in female homicide figures, not all female homicides can be considered femicides. The murder of a woman or girl is considered gender-based and included in femicide statistics when one of seven criteria is met, including evidence of sexual violence prior to the victim’s death; a sentimental, affective or trusting relationship with the perpetrator; or the victim’s body being displayed in public. At present, about one in four female killings in Mexico is classified as a femicide. However, the rates at which the murders of women are classified as femicides vary substantially across states. In 2024, for example, 100 per cent of the murders of women in Campeche were classified as femicides, compared to only 4.2 per cent in Guanajuato. It is therefore difficult to determine with certainty the true number of femicides in different states and over time.

Despite the multifaceted and grim realities of violence against women in Mexico, there have been some hopeful signs in recent years. The total number killings of women peaked in 2019 and has been steadily falling in the years since. Moreover, the number of killings classified as femicides peaked in 2021 and fell in each of the next three years. These trends are shown in the following table.

Furthermore, while the rates of sexual assault and family violence have more than doubled since 2015, last year marked the first year since the index’s inception in which these sub-indicators reported improvements. Between 2023 and 2024, the national rate of sexual assault fell by 6.1 per cent and the rate of family violence fell by 2.9 per cent.

The substantial gains in women’s representation in government also bodes well for the prospect of more effective institutional responses to gender-based violence. The country’s journey toward gender equality in politics has been a decades-long process marked by both progress and setbacks. In 1923, Yucatán became the first state to grant women the right to vote, and in 1953 women’s suffrage was achieved nationally. Despite initial limitations in political representation, structural reforms and gender quotas implemented in the 2010s gradually increased female participation, leading to a historic near-gender parity in Congress by 2018. Six years later, in 2024, full gender parity was achieved in Congress, and the country also elected its first female president, marking a defining moment in women’s political participation.

As political participation increased for women on the national stage, the country implemented reforms aimed at strengthening protections for women, including against violence, pay discrimination, and other forms of vulnerability. For example, certain reforms mandated that public security and investigative institutions operate with a gender perspective and require public prosecutors’ offices to have specialised prosecutors for cases involving violence against women. In addition, through the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence Against Women (CONAVIM), 73 women’s justice centres have been established in 31 states to provide greater victim support.

While this progress is encouraging, regional bodies have recommended further reforms and innovations for better tackling violence against women. These include improving data collection and information systems, enhancing prevention strategies through greater investment in education, awareness campaigns to challenge harmful gender norms, expanding access to protection and support services, and addressing impunity through better financed and more robust investigative, prosecutorial, and judicial processes.

This article was authored by Carlos Juárez, Director of IEP’s Latin America Program, along with Maria Jose Zermeño and Emilia Zermeño, IEP Research Associates currently completing their studies in international affairs at Northeastern University.