World and environmental leaders at COP28 in Dubai delivered a declaration around ‘Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace’. It involves a voluntary commitment by enrolling countries and organisations to increase climate adaptation efforts, plus provide access to finance for those threatened or affected by climate change who cannot afford to combat it.

The declaration called for “bolder collective action to build climate resilience at the scale and speed required in highly vulnerable countries and communities, particularly those threatened or affected by fragility or conflict, or facing severe humanitarian needs, many of which are Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States.”

The declaration recognises the role that climate action, if managed properly, can play in inclusive peace building via sustainable development and conflict prevention, acknowledging:

The COP28 declaration builds on measures identified in detail in the Ecological Threat Report 2023, which reinforces the importance of working on establishing and reinforcing societal resilience at the core of its recommendations to build and ensure peace and prosperity.

Resilience building is holistic, involving all aspects of a societal system. Part of this holistic approach is recognising the multi-layered links between ecological change, sustainable development, human security and global action.

Faced with such complexity, international agencies need to develop a common understanding on the meaning of ‘resilience.’ Broaden the range of actors involved.

Stronger multilateral cooperation with a wider group of actors is also required for interventions based on systems thinking to be successful.

Modern global governance is characterised by an increase in non state actors, who in many cases, form a large part of program implementation. It is therefore important that proposed solutions ensure their inclusion and input.

In states with the worst threat levels and lowest societal resilience, ecological challenges will act as a ‘threat multiplier’ and worsen instability. This can cause increased conflict and encourages spill-over into neighbouring countries and regions.

Some of these effects include new conflicts and population displacement into other regions, as well as economic dislocation. Focus should be on interventions that mitigate or reduce the risk of conflict.

The scope of the problem is beyond the budget capabilities of all the international agencies combined. As institutional funding decreases, it is clear that private sources need to be leveraged to reduce reliance on taxpayer resources.

The sum of all national governments’ income is 15 per cent of world GDP. Only a small proportion of government income can be directed towards ecological adaptation and development.

Therefore, these issues must be faced with not only governments and NGOs, but also the private sector.

For example, if global pension funds were to allocate just one per cent of their assets to ecological threat resilience building programs, the investment would constitute around $500 billion. This is more than three times the OECD’s annual allocation in official development assistance (ODA) and would go a long way towards averting more serious humanitarian crises and economic disruptions.

Solutions to ecological problems require short-term costs with long-term benefits. Adapting to increasing ecological shocks requires sectoral reallocations.

As with any budgetary restructure, there will be winners and losers.

For example, decarbonisation to mediate long-term temperature change means moving away from carbon-intensive sectors, which many countries heavily depend on.

As sectoral reallocations will negatively impact certain workers, businesses and investors, there needs to be further analysis of its effect on these groups (for instance coastal farmers and coal miners).

In regions with already low resilience, the ability to successfully navigate this transition will be further hindered by tight budgets. Many of the solutions to ecological problems can generate income, such as the provision of water which can then be used to grow food.

If business can clearly see how to garner a profitable return from ecologically positive investments, funds will naturally flow towards ecological solutions.

Due to the strong bonds within communities, cooperatives can work well, providing a mechanism for pooling of resources and sharing of costs.

Many examples exist including shared water resources, seed and fertiliser banks, and micro-manufacturing plants. They highlight the need to empower local communities to address the contextual challenges they face.

Community-led approaches to development and human security lead to better program design, easier implementation and more accurate evaluation.

Initiatives led by locals usually benefit from more accurate local knowledge, deeper awareness of local sensitivities and usually enjoy greater community buy-in. Such initiatives tend to run more smoothly and at lower research and implementation costs than others.

They also avoid the “one size fits all” approach of top-down interventions. Designed effectively, these bottom-up approaches can work in tandem with programs initiated at a higher level by governments and multilateral organisations.

While successful developmental programs can be implemented in isolation, a better outcome can be achieved when a well-planned set of interventions is developed from a systems perspective and consider a range of factors, including security responses, governance initiatives and community engagement.

In creating systemic change, smaller “nudges” are preferable to large scale interventions. A large scale mistake is difficult to recover from, whereas minor changes can be undone more easily. In addition, drastic changes – even those in the right direction – can be disruptive and, in extreme cases, destabilising.

If institutions themselves are not set up systemically, it can lead to issues including inefficiencies, partial solutions, inter-organisational disagreements and duplication. There needs to be a common understanding of how the system currently operates and what the desired change is.

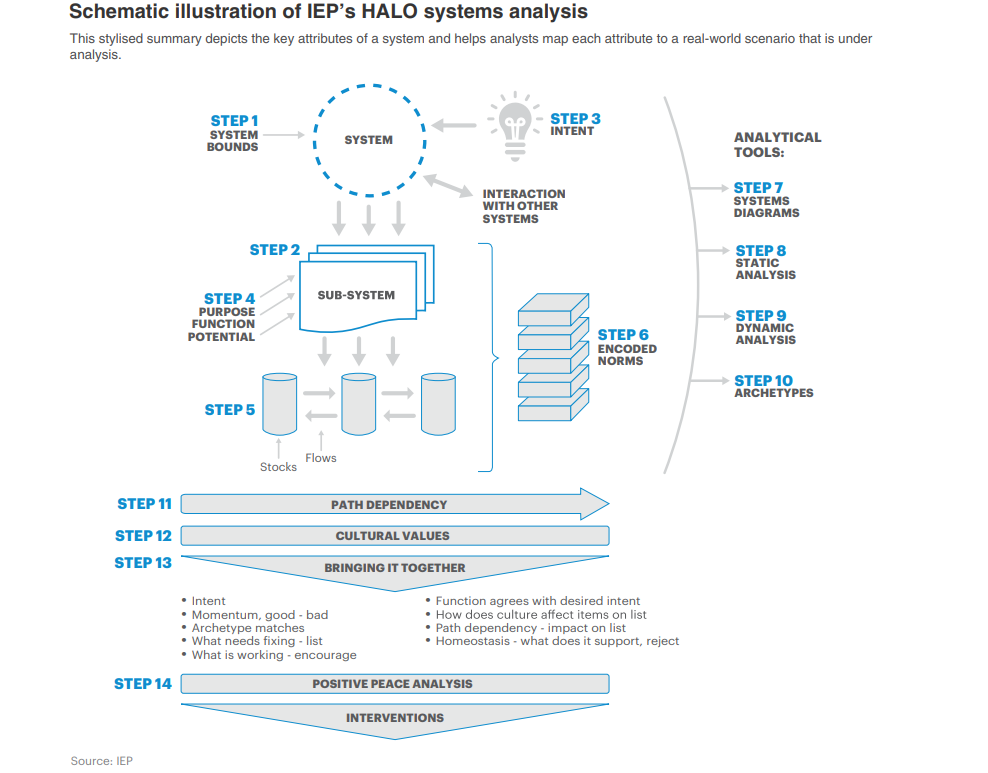

Currently there is no agreed holistic process for stakeholders to conduct a collective mapping system of operation. In recognition of this gap, IEP developed and published a process to allow practitioners to build a more holistic systems picture of societal issues.

Called HALO, it presents a set of 24 building blocks for the analysis of societal systems and the design of resilience-building programs.

Downloads