As Sudan enters its third year of full-scale civil war, the conflict shows no sign of abating, with U.N. officials labelling it the largest and most devastating humanitarian crisis in the world. The war has been marked by mass displacement, worsening famine, the collapse of essential services, and widespread reported human rights abuses. 25 million Sudanese civilians, over half of its population, are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance and protection. While estimated death tolls vary significantly, the former U.S. envoy for Sudan has suggested that as many as 150,000 people have been killed since the conflict’s outbreak.

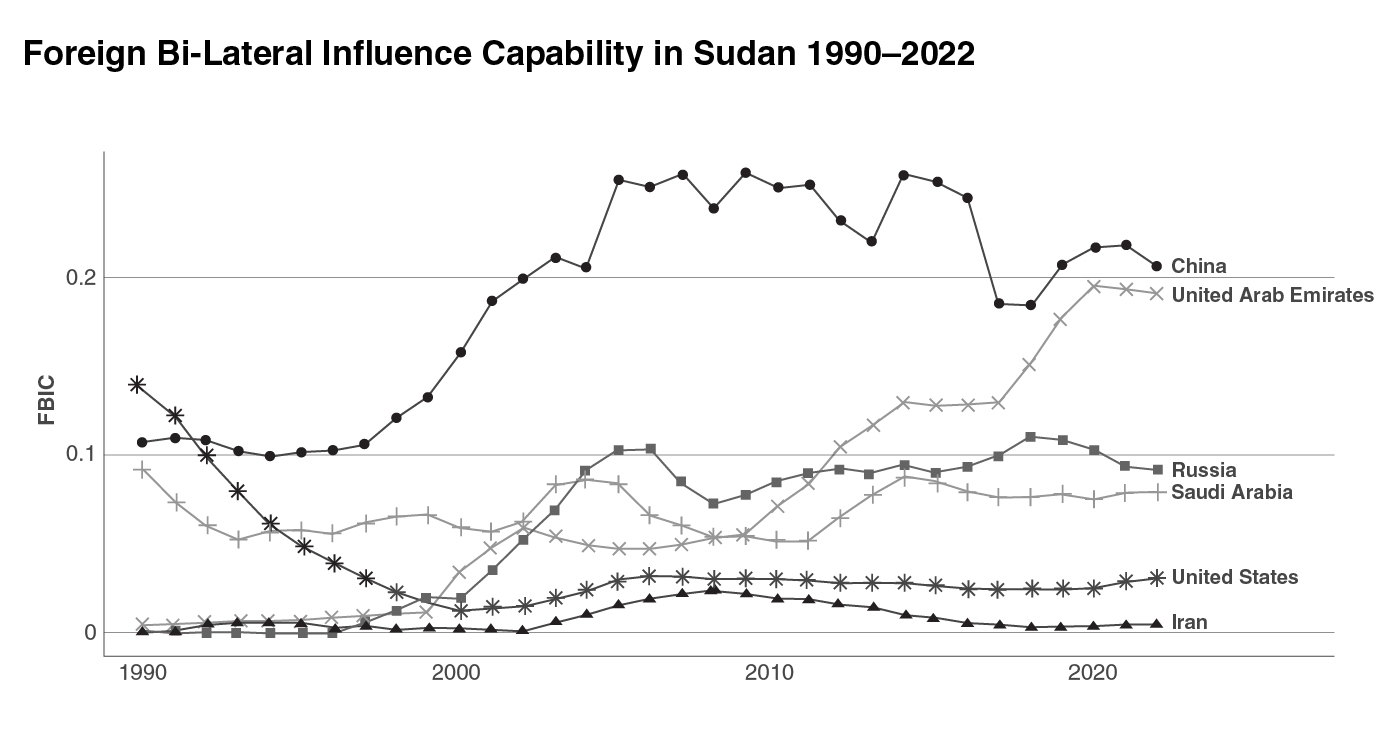

External actors have increasingly shaped the course of this conflict. What began as an internal power struggle has transformed into an international battleground driven by broader geopolitical interests. Sudan’s political instability has attracted foreign actors who seek to capitalize on the conflict to expand their influence. These dynamics exemplify the complexities of contemporary warfare, where conflicts are increasingly protracted and less responsive to traditional forms of resolution. Sudan stands as a critical test case for whether the international system can effectively address 21st-century conflicts, driven by opaque networks of regional and global actors vying for influence.

This conflict began in April 2023 after tensions between two rival military actors, the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), escalated into armed conflict. Following the 2019 ousting of longtime authoritarian leader Omar al-Bashir, Sudan formed a fragile transitional government through a power-sharing agreement between civilian leaders and the military. However, this arrangement collapsed in 2021 after a military coup staged through an alliance between the SAF and RSF. This coup quickly devolved into a power struggle between the groups for dominance over Sudan’s political and security landscape.

The conflict has seen dramatic shifts in territorial control since its outbreak. The RSF made rapid territorial gains in the early months, seizing most of Khartoum and forcing the SAF to retreat eastward. By late 2023, the RSF controlled most of the Darfur region in Western Sudan and had seized Wad Madani, a strategic city for trade routes east of Khartoum. However, in the latter half of 2024, the SAF launched a coordinated offensive and began to counter the RSF’s stronghold. In January 2025, the SAF recaptured Wad Madani, and in March, retook control of the capital, Khartoum. Despite territorial losses, the RSF has demonstrated evolving technological capabilities. In May 2025, they launched unprecedented drone strikes against Port Sudan, Sudan’s temporary wartime capital and vital maritime gateway. The RSF has also intensified its offensive against El Fasher, one of the SAF’s last remaining bases in the Darfur region.

Throughout this conflict, both the RSF and SAF have been accused of extensive human rights violations against civilians. In Darfur, the RSF has been implicated in numerous accounts of ethnic cleansing targeting the Masalit and other non-Arab communities. Reports document systematic atrocities, including mass killings, sexual violence, and forced displacement. In February 2025, the RSF launched a large-scale ground assault on Zamzam camp near El Fasher, Sudan’s largest displacement camp that sheltered over 500,000 people. This series of attacks resulted in heavy civilian casualties and exacerbated the humanitarian crisis in the region. Both groups have also reportedly engaged in widespread killings of civilians, repeatedly obstructed humanitarian aid, and conducted deliberate attacks on civilian infrastructure.

The SAF continues to function as the de facto representative of the Sudanese state in international forums, such as the African Union and the United Nations. In contrast, the RSF originated from the Janjaweed militias during the Darfur conflict and was later integrated into the state apparatus. While both were formerly part of the official state structure, many international actors have been reluctant to recognize the latter as a legitimate state security entity. In April 2025, the RSF signed a provisional constitutional declaration to establish a parallel government structure, although this currently lacks any broader legitimacy. Most international forums have refrained from endorsing either actor, instead advocating for the restoration of civilian-led governance in Sudan.

Sudan’s conflict has become a destabilizing force throughout Northeast Africa and the broader Sahel region. As of May 2025, nearly 13 million people have been displaced, with significant spillover effects into neighbouring countries. Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, Libya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda and the Central African Republic have all experienced a significant influx of refugees. These countries, already facing their own political instability and economic challenges, are now struggling to manage the increased strain on resources and essential services. The civil war has also significantly disrupted Africa’s interdependent trade routes, exacerbating economic challenges across the region. Severe funding shortages, driven by reductions in official development assistance from several countries, have significantly disrupted the availability of aid.

South Sudan has seen an influx of over a million individuals, most of whom are South Sudanese nationals who had previously sought refuge in Sudan. The South Sudanese government has received reports of the RSF operating in its northern regions and allegedly detaining military personnel. This spillover of violence is likely to heighten tensions within South Sudan, which is grappling with its own humanitarian crisis and is struggling to sustain its peace agreement. U.N. officials warn that the country is on the brink of relapsing into full-scale civil war, raising concerns about the risk of a broader regional conflict.

Regional players have provided support to either group in Sudan, with their choices shaped by a combination of long-term strategic goals, ethnic or clan ties, and security considerations. For example, Egypt has been steadfast in its support for the SAF, potentially viewing its formal organizational structure as a more reliable partner in regional negotiations, particularly regarding dialogue over the Nile. Saudi Arabia, sharing Egypt’s concern over regional stability and safeguarding its investments in Sudan, has also extended support to the SAF. Both countries have provided the SAF with significant military aid and diplomatic backing in international forums.

In contrast, Chad has been implicated in facilitating arms transfers to the RSF. While some suggest this relationship may be influenced by cross-border Arab tribal connections, Chad’s approach may also be driven by practical realities, with the RSF controlling most of Darfur along Chad’s eastern border, making them a necessary partner for managing immediate security concerns. These include preventing the spillover of violence, controlling refugee flows, and containing cross-border militant activity. The precise nature of Chad’s support remains difficult to determine.

Similarly, Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), which dominates eastern Libya, has reportedly maintained close ties with the RSF. These ties reportedly involve arms transfers, logistical coordination, and the use of Libyan air and ground bases as launching points for cargo shipments. Given their similar paramilitary structures and tribal networks, Haftar’s forces likely view the RSF as a key regional ally, reinforcing their shared goals of expanding influence and institutionalizing their power. It is documented that the RSF has also recruited fighters from Sahelian Arab tribes across Libya, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and the Central African Republic, reflecting the conflict’s complex transnational dimensions.

According to multiple reports and UN panel investigations, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has provided extensive support to the RSF, though the UAE has consistently denied these allegations. Several investigative reports claim that the UAE has supplied weapons, including its advanced drone technology, to the RSF, potentially through third-party intermediaries or under the guise of humanitarian aid. This alleged support may be connected to the UAE’s interest in Sudan’s seaports, agricultural land, and mineral resources, including gold. The UAE is a primary destination for Sudan’s gold exports, particularly from areas under RSF control. Additionally, the UAE has invested significantly in Sudan’s agricultural sector and port infrastructure. Its support for the RSF may be aimed at protecting these investments and maintaining its influence in the region. In response to this alleged support, Sudan’s defence and security council announced its intention to sever diplomatic ties with the UAE. Sudan also filed a case with the International Court of Justice, accusing the UAE of being “complicit in the commission of genocide” through its alleged role in arming the RSF. However, the ICJ dismissed the case, citing a lack of jurisdiction based on the UAE’s reservation to Article IX of the Genocide Convention when it acceded in 2005.

Russia appears to be balancing its engagement in Sudan by maintaining ties with both the SAF and the RSF. Russia’s Wagner Group, a state-funded private military company, has been active in Sudan since 2017 after facilitating a series of security and economic agreements with then-President Omar al-Bashir, in exchange for gold mining concessions. As the RSF controls many of Sudan’s gold processing facilities, the Wagner Group sought to preserve and expand its mining operations by providing extensive support to the RSF, including weapons, military training, and intelligence assistance. Through front companies such as Meroe Gold, an entity linked to the Wagner Group, the organization facilitated the smuggling and monetization of gold out of Sudan, helping to fund their respective operations.

However, Russia has also begun supporting the SAF amid evolving strategic priorities. In April 2024, Kremlin officials visited Port Sudan and reportedly offered the SAF “unrestricted qualitative military aid.” This marked a notable policy shift, likely driven by Russia’s long-standing interest in securing a strategic foothold on the Red Sea. In 2020, Moscow negotiated an agreement to establish a naval base in Port Sudan, which would have granted it a key position on the Red Sea. Although the deal was suspended in April 2021 by Sudan’s transitional government, recent reports suggest Russia is working to revive the agreement, particularly by maintaining formal state-to-state ties with the SAF if it regains full control over Sudan. Russia is also likely seeking to sever the SAF’s growing alliance with Ukraine, which has reportedly supplied arms and special forces to support the Sudanese army fight against Russian Wagner mercenaries.

This shift may also be influenced by Russia’s desire to align with Iran’s positioning, as Iran has also reportedly been supporting the SAF. Iran’s support may be linked to its goal of securing a presence along the Red Sea coast, a region of strategic importance for both nations. Iran is likely motivated by its desire to counter the UAE’s growing regional influence. While Russia officially claims that the Wagner Group is no longer operating in Sudan, multiple credible sources indicate that Russian mercenaries continue to maintain a presence there. As a result, determining Russia’s exact geopolitical posture in the region remains challenging. Evidence suggests that Moscow may be strategically hedging its bets by cultivating relationships with both sides of the ongoing conflict, thereby ensuring continued influence regardless of the outcome.

Israel has reportedly maintained engagement with both sides throughout the ongoing conflict. In 2020, Israel and Sudan signed a normalization agreement as part of a U.S.-brokered deal in which Sudan’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism was lifted by the Trump administration. In return, Sudan agreed to join the Abraham Accords. As formal diplomatic ties between the two countries remain stalled due to the war, Israel may be engaging both sides to preserve leverage regardless of the outcome. In its broader efforts to expand regional influence and counter Iran’s growing presence, normalization efforts with Sudan offers Israel a strategic foothold, particularly given Sudan’s position along the Red Sea and its ties to the African Union.

China has historically been one of Sudan’s largest investors, particularly within the oil and infrastructure sectors. As Sudan is a key partner in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the two countries have developed strong bilateral ties. Securing its economic investments and access to trade routes provides China with strong motivations to maintain stability in Sudan. In 2024, Sudan’s Military Industry Corporation (MIC) and China’s Poly Technologies signed a strategic defence cooperation agreement during the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in Beijing. As the Sudanese Military Industry Corporation is a SAF-owned conglomerate, this agreement bolsters its defence capabilities and solidifies military ties between China and the SAF. Chinese-manufactured weapons have also reportedly been utilized by both groups. While China affirms its commitment to international arms trade regulations, the presence of these weapons raises concerns about potential transfers through third-party or illicit channels. It remains unclear whether China is directly involved in these transactions. Türkiye has also been implicated as weapons manufactured by its private arms companies were reportedly utilized by both groups, raising similar concerns about unauthorized transfers.

In addition to traditional military tactics, the SAF and RSF have leveraged social media to shape political narratives and recruit fighters. These platforms serve as channels for disinformation and coordinated propaganda campaigns. Concurrently, Sudanese journalists face escalating threats, including documented cases of harassment, arrests, and targeted killings. Independent media outlets reportedly encounter censorship and alleged cyberattacks, severely restricting the flow of reliable information.

These constraints on press activities complicate verification of events on the ground, as each party positions itself as the legitimate stabilizing force while accusing the other of atrocities. Furthermore, analysis has traced social media accounts linked to foreign countries, including Russia, the UAE, and Egypt, to activities related to the conflict. However, the widespread use of proxy servers and anonymization tools in the cyber domain makes it difficult to accurately assess the extent of external involvement in the digital information space.

While several international bodies have attempted to mediate peace in Sudan, disagreement among key external actors has severely hindered progress. The London Sudan Conference in April 2025 starkly illustrated these divisions, with participating nations unable to develop a joint communique on the terms of a peace agreement and the future governance of Sudan. Egypt and Saudi Arabia pushed for amendments that recognized state institutions and implicitly legitimized the SAF-led government, while the UAE advocated for stronger language emphasizing civilian governance. The collapse of consensus at the London Conference reflects a broader pattern of diplomatic deadlock that has characterized international engagement in Sudan. These global power struggles have infiltrated Sudan’s peace process, undermining efforts for a unified and sustainable resolution. Meanwhile, Sudanese people continue to bear the brunt of this prolonged violence, with the humanitarian crisis continuing to worsen. Given its scale and severity, the crisis has received inadequate international attention and support.

As IEP’s Geopolitical Influence and Peace Report discusses, Sudan’s conflict highlights the internationalization of contemporary warfare, with the increasing diffusion of powers globally. As observed in the report, more states are exerting higher levels of influence in more countries than at any other point in history. While foreign involvement in civil wars is not a new phenomenon, its frequency and complexity has increased in recent years. The current geopolitical landscape is marked by “technological dominance, economic interdependence, and influence competition across emerging regions.” As global power struggles intensify, these countries have exploited conflicts to extend their influence while maintaining plausible deniability and avoiding direct confrontation. The growing use of online platforms for narrative control and mobilization highlights the complexity of hybrid warfare, where conflicts extend beyond traditional battlegrounds into the digital space. Sudan provides a stark example of the culmination of these geopolitical dynamics in modern conflicts.

These implications extend far beyond Sudan’s borders, with similar dynamics characterizing current conflicts in Yemen, Syria, Libya, Ukraine, and across the Sahel region. Traditional peacebuilding frameworks, designed for state-based actors and clear accountability, are increasingly inadequate for these complex wars. Hybrid actors, such as foreign mercenaries, armed militia groups, and private military companies wield significant power over the trajectory of these ongoing wars.

These conflicts highlight the urgent need for multilateral peacebuilding strategies capable of addressing indirect involvement, decentralized networks, and hybrid warfare tactics. Without a coordinated international strategy to address foreign interference, external actors will continue to exploit this impunity for their strategic gain. Both warring groups will continue to receive support, and violence will be prolonged for the foreseeable future. If we fail to address these new realities of conflict, we prolong suffering in existing conflict zones and open the floodgates to even greater instability and violence elsewhere. This new face of conflict demands both immediate humanitarian action and a long-term strategic overhaul of multilateral peacebuilding, tailored to these evolving warfare dynamics.