As floodwaters devastate communities already struggling with civil war, Sudan’s vulnerabilities to both human-made and natural disasters are starkly illustrated.

In August, the Arbaat Dam, located just 40 kilometres north of Port Sudan, succumbed to torrential rains. The resulting flood swept away at least 20 villages, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake. Initial reports from the United Nations indicate at least 30 fatalities, with the possibility of a much higher death toll. One first responder reported between 150 and 200 people missing.

The scale of the disaster is immense. Homes of approximately 50,000 people have been impacted, though this figure only accounts for areas west of the dam, as eastern regions remain inaccessible. The flood’s impact extends beyond immediate loss of life and property. Port Sudan, serving as the de facto national capital and a crucial hub for aid distribution, now faces a severe water crisis as the Arbaat Dam was its primary water source.

This disaster has unfolded against the backdrop of a protracted civil war that began in April 2023 between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The conflict has diverted resources from critical infrastructure maintenance, exacerbating the country’s vulnerability to natural disasters. Omar Eissa Haroun, head of the water authority for Red Sea state, described the affected area as “unrecognisable,” with electricity and water infrastructure destroyed.

The dam burst is not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of environmental challenges facing Sudan. The country’s rainy season task force reported that flood-related deaths across Sudan had reached 132 by late August 2024, nearly doubling from 68 just two weeks prior. United Nations agencies estimate that at least 118,000 people have been displaced by rains in 2024 alone.

These events underscore the findings of recent research on ecological threats and food insecurity in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Sudan, along with Yemen, contributes significantly to the region’s extreme food insecurity, affecting 87 million people or 15% of the MENA population. The ongoing conflict has severely disrupted food production and distribution systems, pushing millions towards the brink of famine.

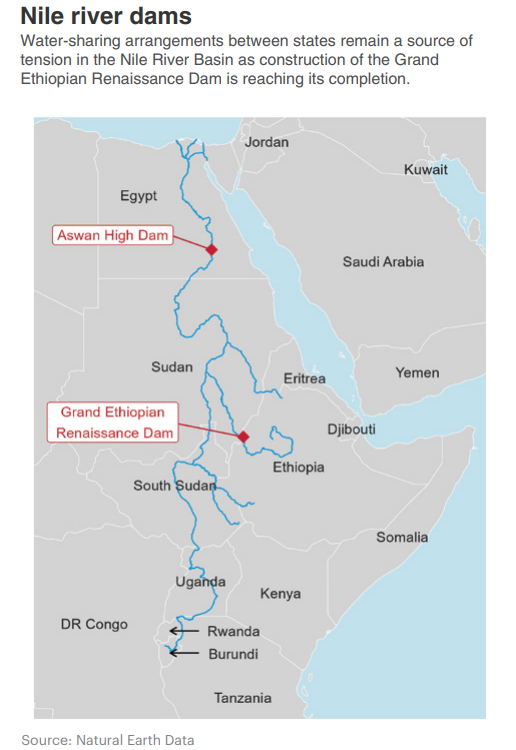

Sudan’s vulnerabilities extend beyond its borders. The country is intricately linked to regional water politics, particularly concerning the Nile River. While historically opposed to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Sudan has recently shown support for the project, hoping it might aid in managing Nile flooding. However, the current crisis demonstrates the delicate balance between water management and disaster prevention in a changing climate.

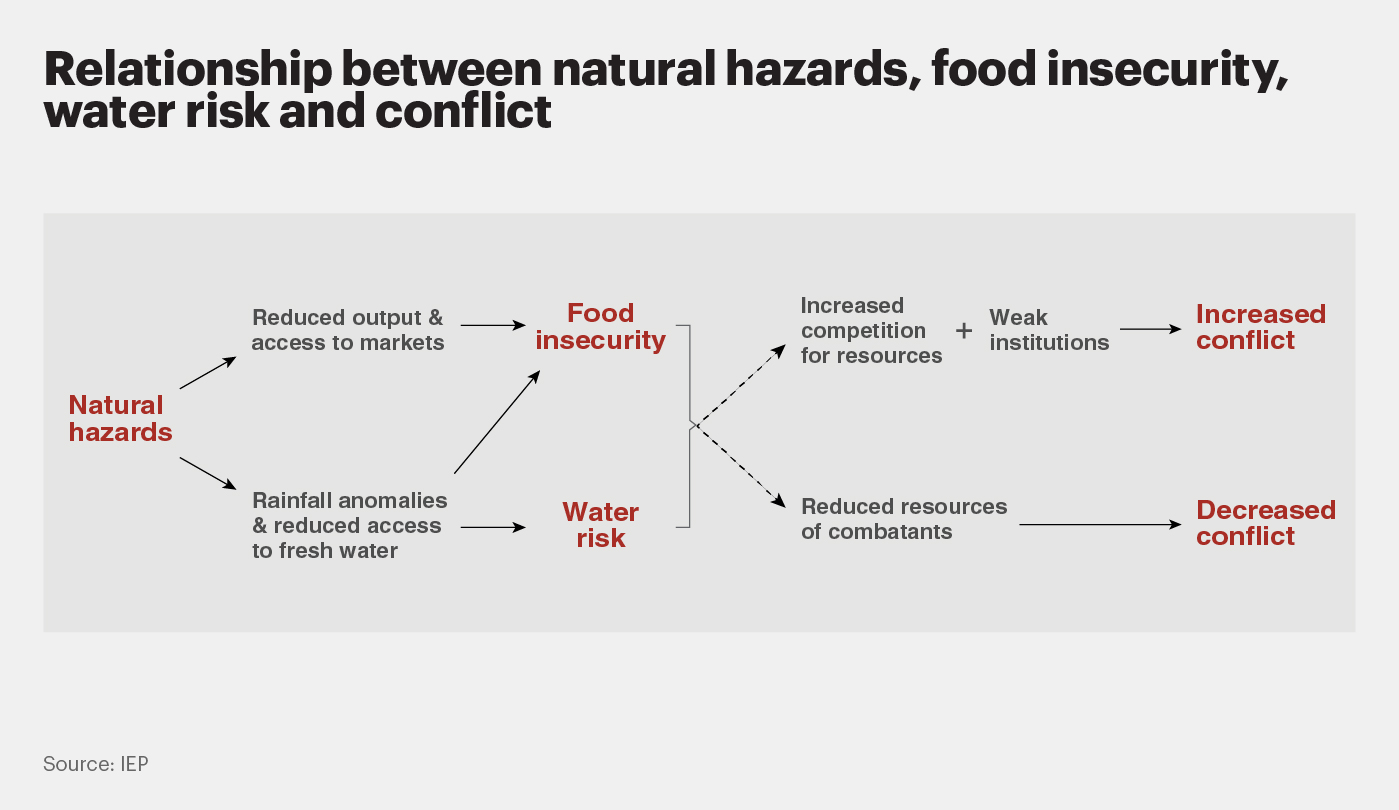

The Ecological Threat Report 2023 classified Sudan as a ‘hotspot’ country, facing at least one severe ecological threat while ranking amongst the 30 countries with the lowest levels of Positive Peace. This designation reflects Sudan’s high vulnerability to natural disasters coupled with limited resilience and coping mechanisms. The country scores poorly across multiple indicators, including food insecurity, natural disasters, demographic pressure, and water risk.

Looking ahead, the challenges are likely to intensify. Projections indicate that sub-Saharan Africa’s population will reach 2.2 billion by 2050, a 60% increase that will place unprecedented pressure on food and water resources. Sudan, with its current struggles, appears ill-prepared for this demographic shift.

The ongoing conflict further complicates Sudan’s ability to address these environmental and humanitarian challenges. The war has led to widespread displacement, with millions forced from their homes. Reports of violence against civilians, including allegations of massacres by the RSF, have created an atmosphere of fear and instability. This insecurity has severely hampered the efforts of humanitarian agencies and multilateral organisations to operate effectively in most parts of the country, including the capital, Khartoum.

The Global Peace Index 2024, released in June, painted a sobering picture of Sudan’s situation within the broader regional context. Sudan ranks 162nd out of 163 countries in overall peacefulness, reflecting the severe impact of the ongoing conflict. The MENA region as a whole remains the least peaceful globally for the ninth consecutive year, with four of the ten least peaceful countries located within the region.

The interconnected nature of these challenges – conflict, environmental disasters, food insecurity, and population pressure – creates a complex crisis that defies simple solutions. Addressing any single aspect in isolation is unlikely to yield sustainable improvements. Instead, a holistic approach that considers the interplay between these factors is necessary.

International attention and support will be crucial in helping Sudan navigate its current crises and build resilience against future threats. However, the effectiveness of aid efforts is severely compromised by the ongoing conflict. A ceasefire and a path towards stable governance are essential prerequisites for meaningful progress.

As Sudan grapples with the immediate aftermath of the Arbaat Dam disaster, the incident serves as a stark reminder of the country’s precarious position. It underscores the urgent need for conflict resolution, infrastructure investment, and comprehensive planning to address both immediate humanitarian needs and long-term ecological challenges. Millions of Sudanese citizens and their neighbours have their future well-being closely tied to Sudan’s ability to forge a path towards peace, stability, and environmental resilience.