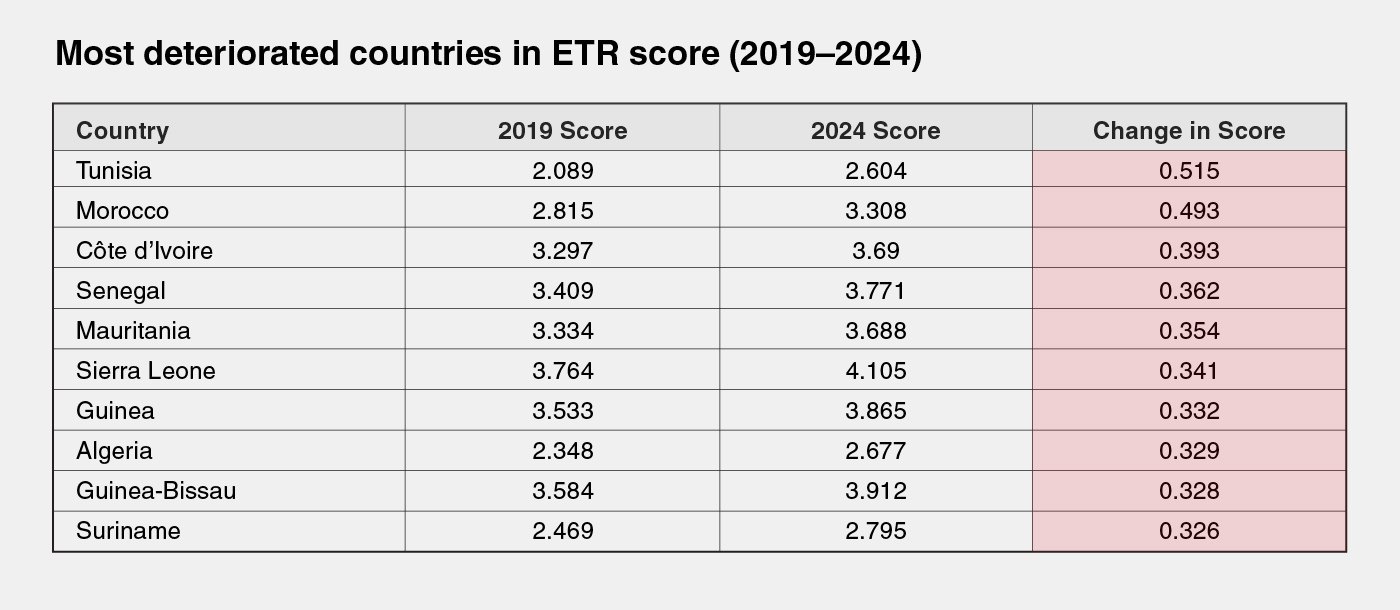

The 2025 Ecological Threat Report (ETR), reports on the emerging trend of heightened water insecurity, most notably across northwestern Africa and coastal West Africa. Nine of the ten largest deteriorations in ETR scores occurred in these areas.

Since 2019, Tunisia has recorded the steepest rise in ecological threat of any country assessed in the ETR, driven primarily by worsening water insecurity and mounting impacts of natural events. A sequence of prolonged droughts, severe heatwaves, and increasingly erratic rainfall has undermined Tunisia’s ability to store and distribute freshwater. These stresses have been compounded by under-resourced infrastructure and limited governance capacity, leaving millions of citizens vulnerable to extended shortages and eroding trust in institutions.

The challenges in Tunisia are not unique, but they are among the most severe. Of the 20 subnational areas that deteriorated the most between 2019 and 2024, nine were in Tunisia. This included Manouba, part of the greater Tunis metropolitan area, which registered the largest subnational deterioration globally.

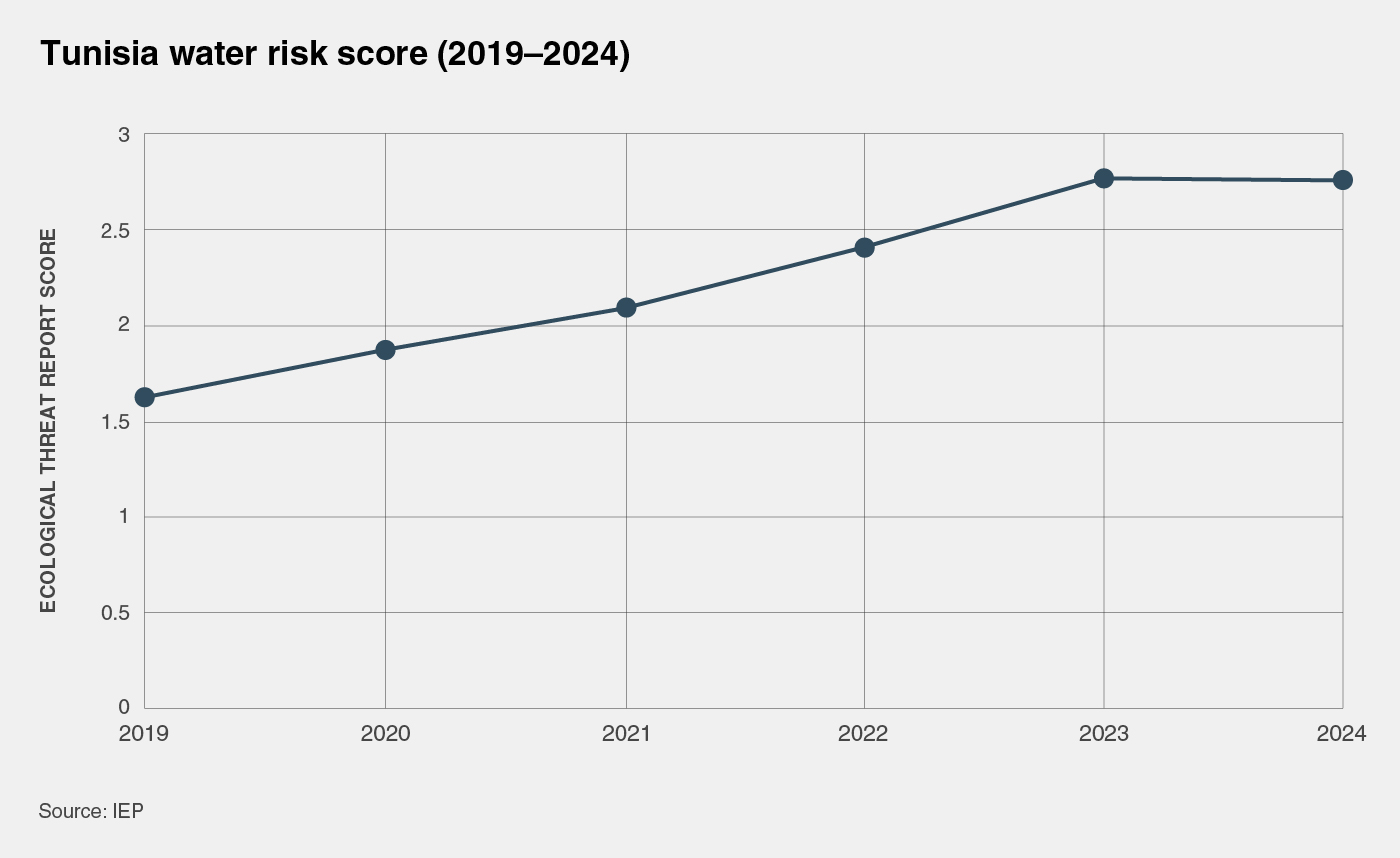

These deteriorations were driven by an almost 70% increase in the national water risk indicator, which deteriorated within every subnational area in the country. Notably, this change was amplified by an unusually favourable baseline year in 2019, in which North Africa experienced relatively high rainfall.

By 2024, Tunisia’s entire population resided in medium-risk zones and its dam water reserves decreased by 27%. Extended droughts and record temperatures not only depleted available water reserves but also disrupted traditional rainfall patterns, which exposed the country’s vulnerability to changing climatic conditions, with cascading impacts on households, communities, and local economies.

Tunisia’s water scarcity is as much infrastructural and institutional as it is climatic. Decades of underinvestment and insufficient maintenance has left the country’s pipe networks losing around 30% of total supply through leakages. Losses which were once considered manageable have become dire amid multi-year droughts.

In 2024, Tunisia’s Water Observatory recorded more than 2,100 unannounced water cut-offs, many exceeding 10 hours. Households and businesses alike were forced to ration supplies, often without warning, undermining trust in institutions. The government imposed official restrictions in an effort to stabilise reserves, but these measures exposed the underlying fragility of the system.

Tunisia’s water scarcity is as much infrastructural and institutional as it is climatic.

Tunisia’s deepening water crisis has triggered recurrent waves of social unrest, with 186 protests recorded in 2024 alone. Water scarcity related protests have now become a defining feature of the country’s summer months. In 2023, the crisis reached major urban centres as Tunisia imposed some of its first-ever national water rationing in certain regions.

Underlying the unrest are structural governance and environmental challenges that have eroded public confidence in state institutions. Successive years of drought and heat have depleted reservoirs, while outdated irrigation systems, leakages and overuse by industry have deepened scarcity. Around 74% of Tunisia’s water is consumed by agriculture, often for water-intensive export crops, leaving limited reserves for households.

Persistent institutional inequities, where municipal sectors face chronic neglect while export-oriented agriculture receives priority, have deepened public grievances. Water scarcity has thus evolved from an environmental challenge into a matter of social justice, entwined within broader dissatisfaction over governance, inequality and government accountability.

Water scarcity has evolved from an environmental challenge into a matter of social justice, entwined within broader dissatisfaction over governance, inequality and government accountability.

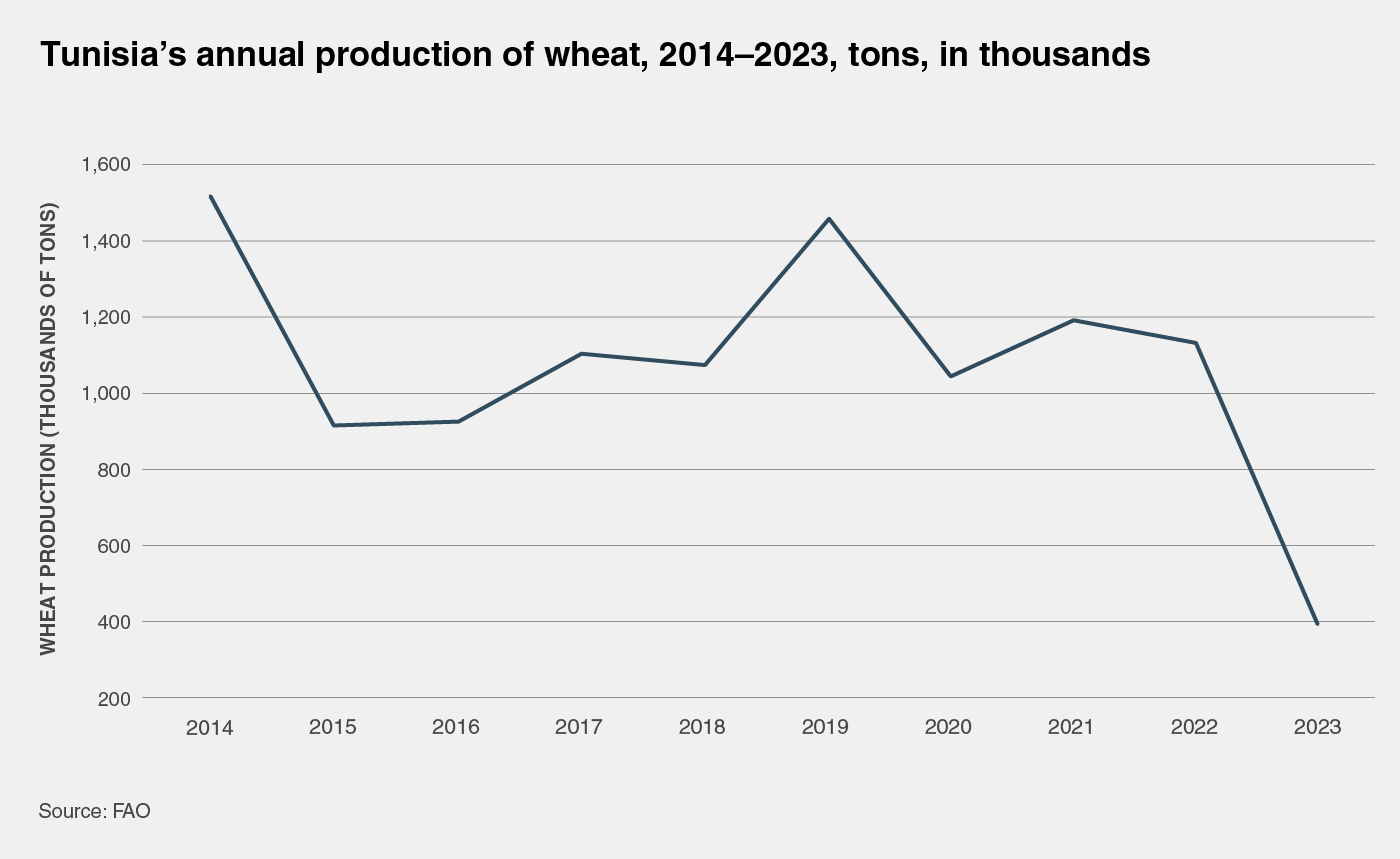

The agricultural sector’s extensive water demands have intensified scarcity, yet the sector itself remains among the most vulnerable to the resulting pressures. Agriculture in Tunisia is largely dependent upon rainfall and limited irrigation, with only around 9% of the country’s cultivated area equipped for irrigation, leaving many farmers acutely vulnerable to fluctuations in rainfall. Recurrent droughts have slashed output, reducing the share of the national workforce employed in agriculture by approximately 5% over the past decade.

The unpredictability of planting cycles has reduced productivity and shifted employment toward already strained urban economies, undermining food production of vital crops. Tunisia’s most produced commodity, wheat, has experienced some of the sharpest declines. Between 2022 and 2023, total wheat production fell by nearly two-thirds, forcing the country to rely more heavily on imports. As a result, food prices have nearly doubled since 2021, deepening economic hardship for households already coping with rising water costs and reduced purchasing power.

Tunisia’s worsening water-risk is part of a broader belt of ecological deterioration extending from northwestern Africa to coastal West Africa, with four of the five most deteriorated countries in water risk located within this region. The rapid escalation of water risk, exacerbated by ageing infrastructure and prolonged climatic shocks, has heightened the human costs – with greater interruption of supplies, rising food prices and mounting social discontent.

Tunisia’s worsening water-risk is part of a broader belt of ecological deterioration extending from northwestern Africa to coastal West Africa.

Without sustained investment, the region risks entrenching vulnerability at precisely the moment when resilience is most needed. Water insecurity is not an isolated challenge but a systemic, transboundary threat. The Medjerda River, for example, flows across the Algeria–Tunisia border, serving as a vital water source for Algeria while supporting the livelihoods of around 13% of Tunisia’s population.

As the Middle East and North Africa recorded the greatest overall rise in ecological risk globally, Tunisia’s experience stands as a warning: without urgent action, worsening water insecurity could erode livelihoods and intensify political instability across the wider region.

Further reading: