The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body for assessing the science related to climate change, shed more light of this. It projected worse fires, longer droughts and increasing numbers of floods in the future, with these types of weather events frequently leading to mass displacements.

The number of people migrating due to climate change is expected to rise substantially in the coming years. There are already 17 countries where at least 5% of the population are either refugees or internally displaced, which puts massive pressure on these societies as they struggle to cope. Displaced people make up over 35% of South Sudan’s population, and over 20% of those in Somalia and the Central African Republic.

The World Bank estimates that climate change will create up to 86 million additional migrants in sub-Saharan Africa, 40 million in South Asia and 17 million in Latin America, as agricultural conditions and water availability deteriorate across these regions; leading to a total of 143 million climate migrants by 2050.

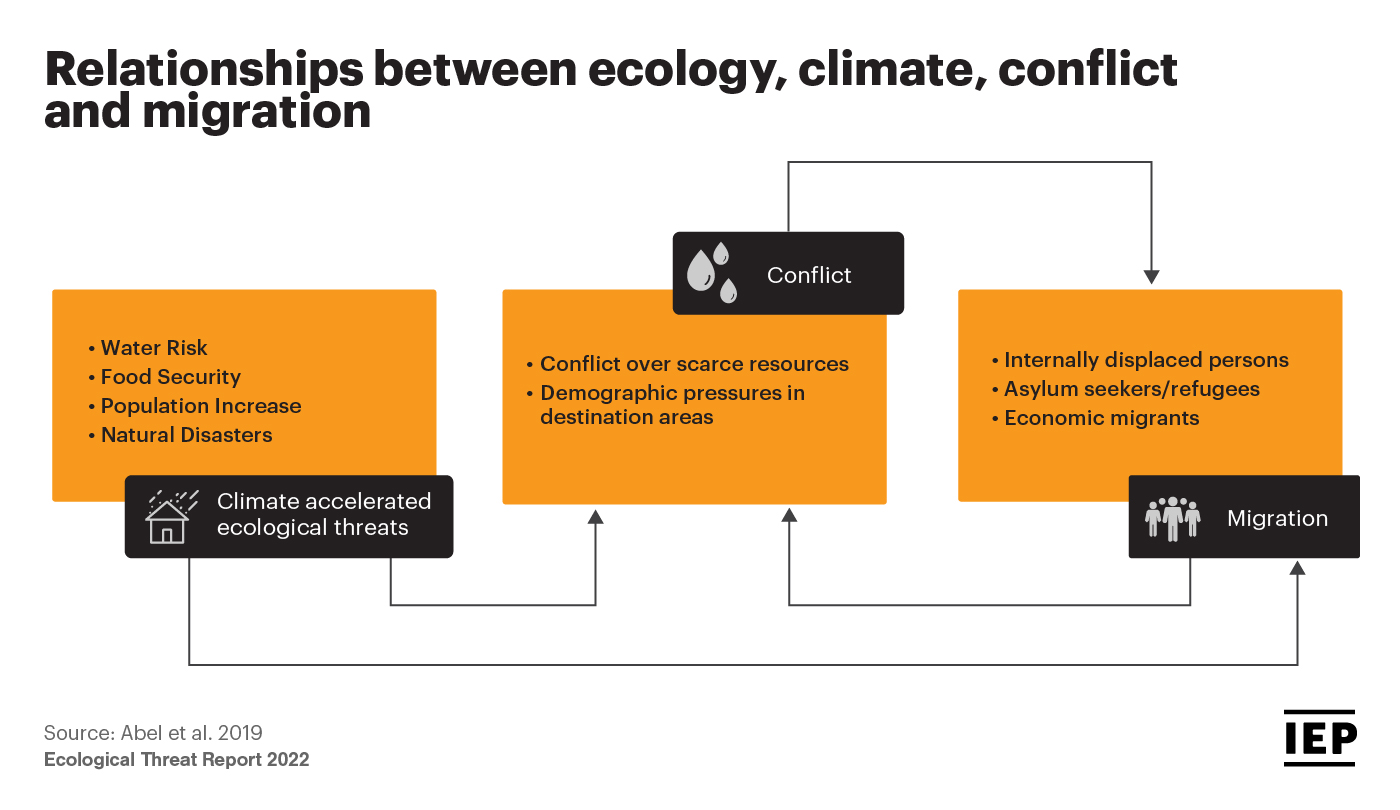

Population displacement on this large scale leads to resource pressure on the towns, countries and communities receiving migrants and can exacerbate existing instabilities. For instance, in countries lacking the institutional capacity to manage an influx of migrants, or those already engaged in internal conflict, migration on this scale greatly increases the potential for violence.

There are currently 2 billion people residing in countries facing catastrophic ecological threats, however, research from the 2022 ETR projects that by 2050 this number will reach 3.4 billion. This will account for nearly 35% of the world’s population.

Recognition of the link between changes to climate, forced migration and conflict is rising, and the term ‘Climate-Security Nexus’ has risen in prominence.

Syria, Afghanistan and South Sudan are among the top five countries with the largest displacements from conflicts. These countries are ranked 161st, 163rd and 159th respectively on the 2022 Global Peace Index, and make up three of the world’s four least peaceful countries. These countries are also juggling significant climate-related threats with low societal resilience. Syria and Afghanistan face a high risk of drought, while South Sudan is faced with a significant risk of flooding.

Countries with low levels of peacefulness tend to have a lower coping capacity, which puts them at higher risk of further deterioration in peace.

Syria serves as a prominent example of how climate-related issues can intensify existing social and political grievances, which leads to unrest, particularly in fragile countries with poor governance. From 1999 to 2011, Syria underwent two long-term droughts. About 75% of farmers experienced total crop failure and in the northeast, farmers lost 80% of their livestock.

Extreme rural to urban migration ensued, with an estimated 1.3 to 1.5 million rural citizens migrating to urban centres by 2011. In 2011, a World Bank survey of Syrian migrants showed that 85.3% of respondents used migration as an “adaptation strategy.” Frustration with the government response to these environmental and development challenges sparked unrest in Syria; with uprising notably beginning in poor, marginalised neighbourhoods with high numbers of rural migrants.

In Ethiopia, droughts in the mid-1970s and 1980s and subsequent famines led to waves of mass migration from drought-stressed areas, both voluntary and government-forced. In this case, both climatic and political factors influenced population displacement and international migration. As a result of this instability, violence and insecurity increased in neighbouring countries, destabilising the entire region.

In Central America, the livelihoods of more than five million small-scale farmers in Mexico were negatively impacted by climate-related variables, namely drought from 2002 to 2012. As a result, internal migration flowed to the slums of Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey, as well as internationally to the United States.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects that Mexican land available for corn production will decrease by between 13 and 27% by 2050. Consequently, it is expected that 3.25 to 6.75 million farmers will lose their livelihoods, further driving environmentally forced domestic and international migration.

In 2021, IEP held a series of seminars with leading academics, policymakers and experts from military institutions and think tanks to explore policy options to address some of these ecological threats. As has been explored, many of the countries that are the most vulnerable have the lowest resilience and capacity to cope. It is when these shocks happen that mass migration is often triggered. In order to prevent situations like the mass migration that preceded the Syrian conflict, the key is to focus on building the resilience of these high-risk areas.

The recommendations suggested in the 2022 ETR are all focused on building the resilience of at-risk communities and fall under three categories: fostering water resilience, increasing resilience in food systems, and promoting rural development. From dam-building to improving crop productivity, these interventions make a tangible difference in reducing the impact of climate crises. It is only through holistic approaches, such as these, communities will have the resilience and capability to avoid humanitarian emergencies and reduce conflict which will ultimately reduce forced migration.

Further Reading: Resilience Building Key to Decreasing Impact of Ecological Threats