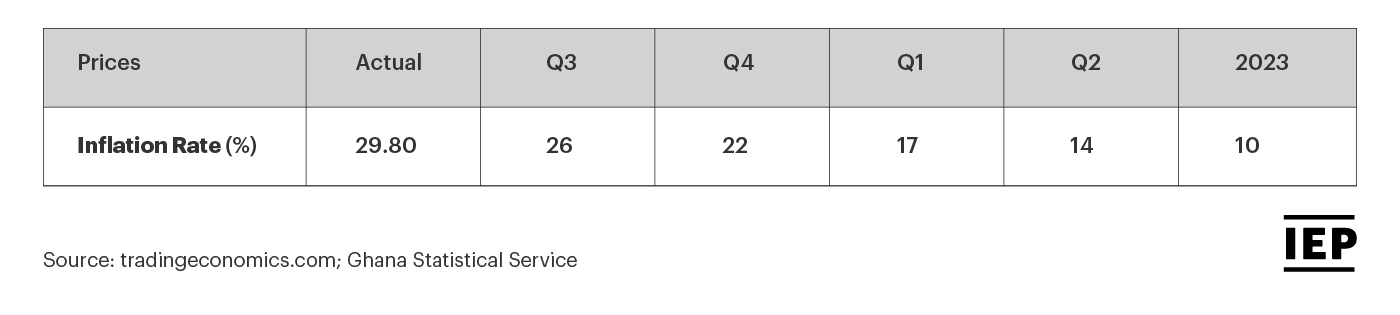

Ghanaians took to the streets of Accra, protesting, at the start of July. Inflation in Ghana had hit almost 30% and living costs spiralled as the cost of imported goods continued to rise higher than the cost of domestically produced goods.

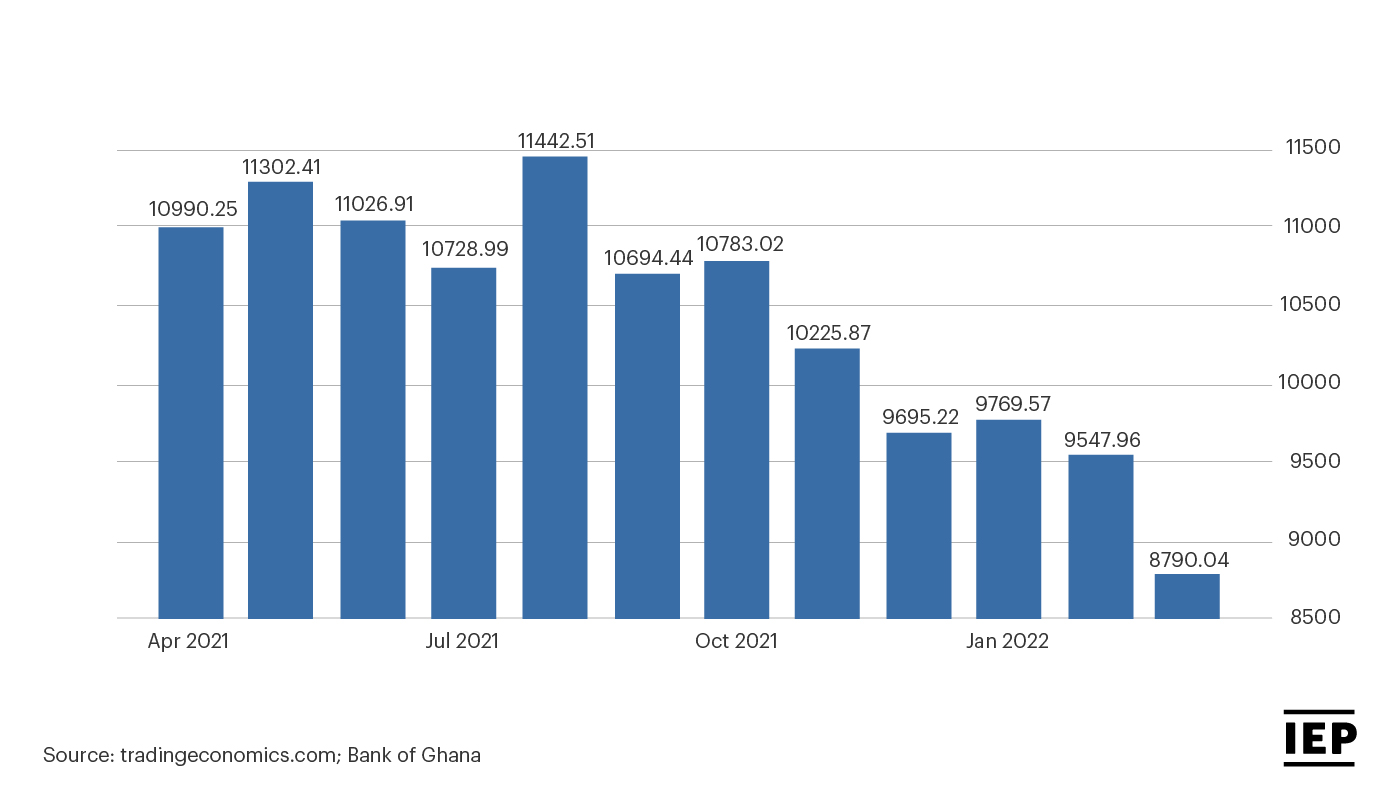

At the same time their currency, the Ghanaian cedi (GH₵), had depreciated by almost 20% against the US dollar(1). Furthermore, Ghana’s foreign exchange reserves plummeted by over US$2 billion over the last 12 months, from US$10.99 billion in April 2021 to US$8.79 billion in April of this year(2).

In the wake of these protests and in the face of extreme economic difficulties, the government of Ghana approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for assistance for the second time in three years. The IMF then visited Ghana, between 6 July and 13 July, to discuss a bailout in an effort to rescue Ghana’s flailing economy.

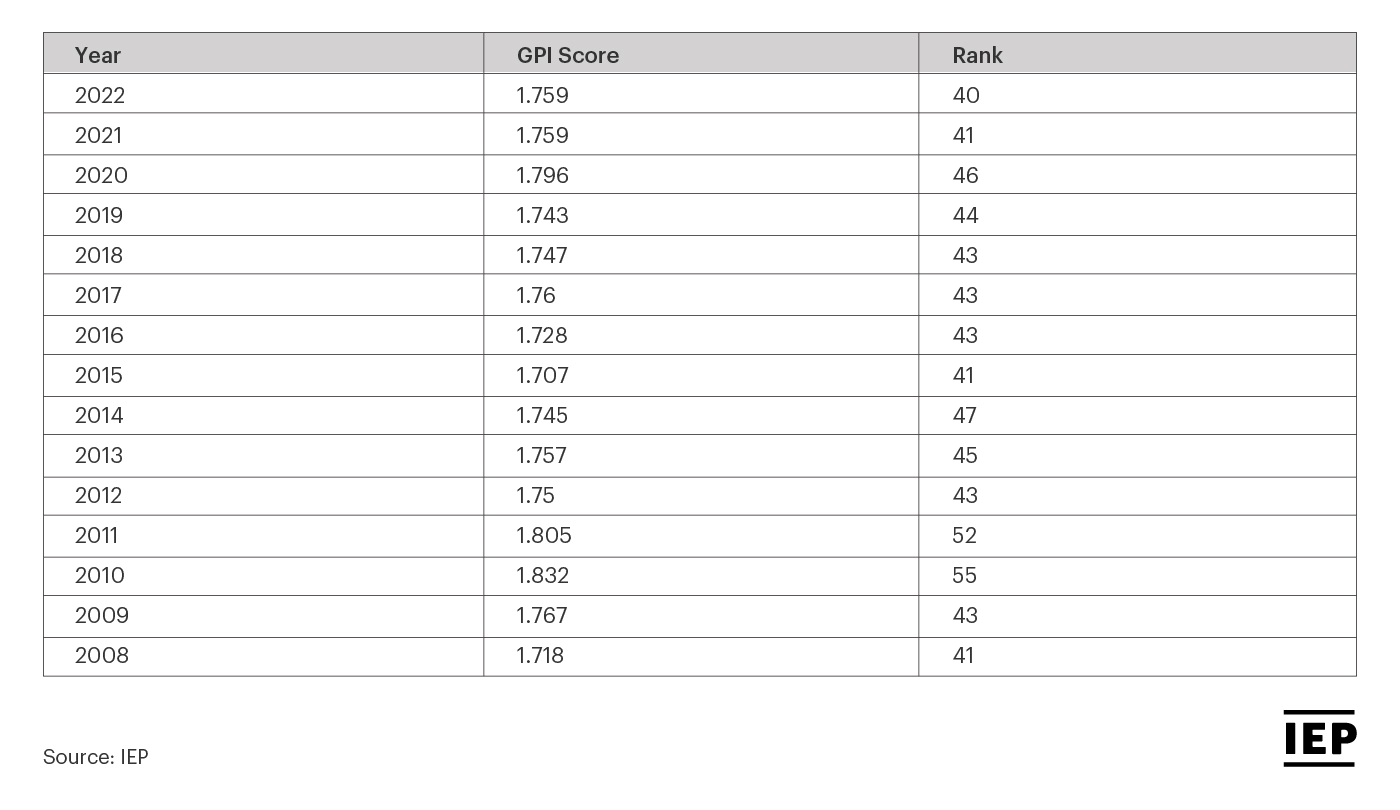

Ghana had long been presented as a success story within the region. Peacefulness within Ghana had remained stable over the last decade, shown by the relatively high position it maintained on IEP’s Global Peace Index (GPI). Ghana has consistently been among the highest ranked African nations since the inception of the GPI.

Over the last couple of years, a combination of issues including the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have produced enormous economic ripples across the world. While these events are having tangible impacts on many countries, it has been felt particularly keenly in Ghana for several reasons.

As a major exporter of oil, Ghana should have benefited from the sharp rises to oil prices triggered by the conflict in Ukraine. However there has been long-term underinvestment in Ghana’s oil refining capabilities, with the government preferring to export crude oil and importing over 80% of the domestically used refined products such as petrol and diesel(3).As a result, Ghana’s transport and energy prices have been the key drivers of inflation and are among the most significant factors contributing to the burgeoning cost of living crisis.

Ghana also imports around 20% of its cereals from Russia, and the invasion of Ukraine has dramatically impacted the cost and feasibility of these imports. This, coupled with the global spike in oil prices, has sharply increased agriculture costs and driven up the price of food in Ghana.

Ghana’s economy has also been mismanaged. Successive governments overspent in the run-up to elections or when economic conditions appeared to be improving instead of implementing a sustainable, long-term economic strategy(2). An overreliance on imported goods has also left Ghana extremely vulnerable to economic shocks, as proven over the last few years.

An increasing reliance on Chinese investment has also left Ghana somewhat vulnerable and impacted Ghana’s economic stability. Ghana agreed to carry out a number of expensive infrastructure projects with Chinese companies. However, as the Chinese economy has begun to slow down, so too has Chinese investment in Ghana, leaving projects unfinished and costing jobs.

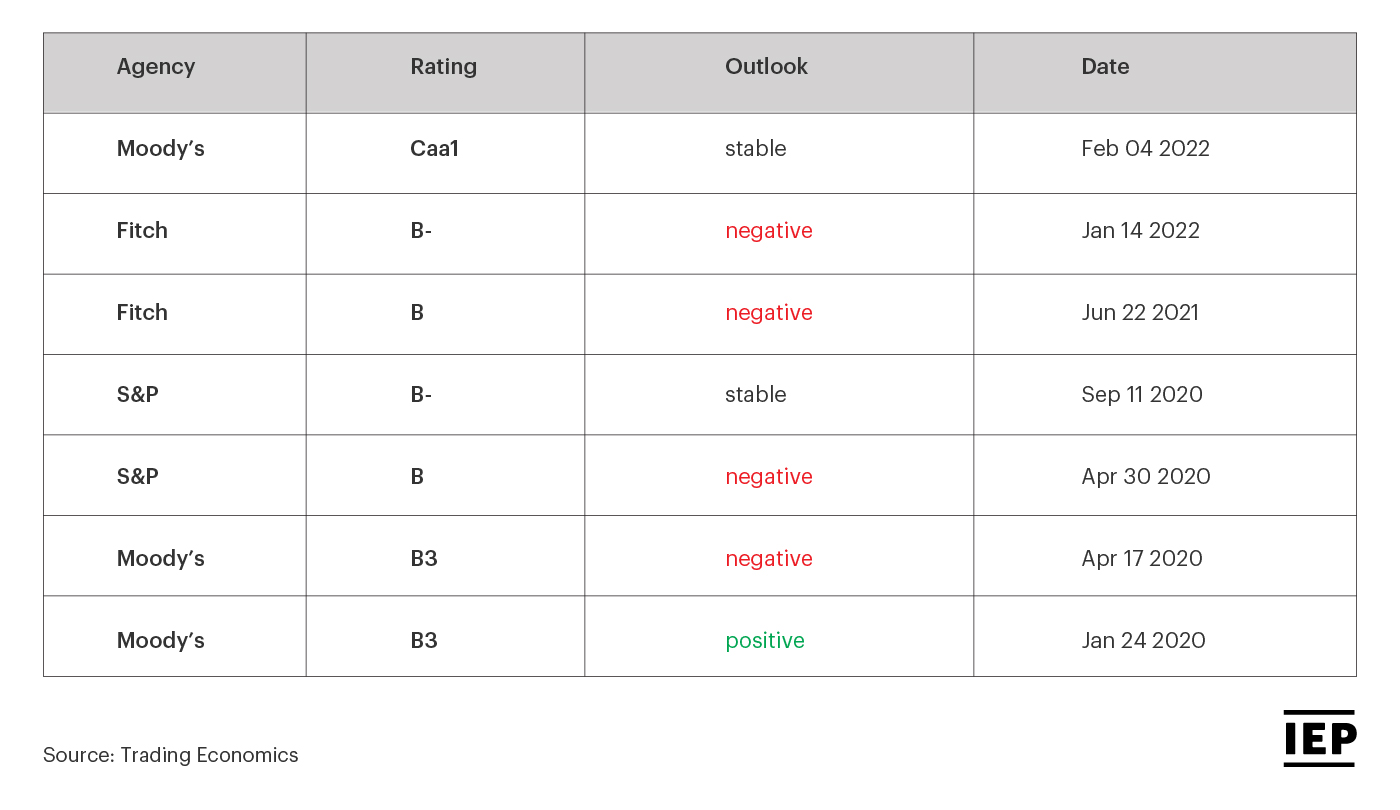

As a result of the complex and compounding challenges facing Ghana’s economy, credit rating agencies such as Moody’s have downgraded their rating of Ghana’s economy further impacting the country’s ability to recover(4).

Credit ratings are essentially judgements on the economic stability of a country as a borrower. These ratings operate on a scale from ‘most secure’ (when a borrower is perceived as being highly likely to meet their financial obligations) to ‘least secure’ (when a country is deemed to be highly unlikely to be able to repay debts). Changes to credit scores can be prompted by several triggers such as economic or political conditions.

These ratings have tangible implications for the countries who receive them, with countries given a lower rating being perceived as a higher risk by lenders. As a result, borrowing becomes more challenging, often incurring significantly higher costs.

For companies and individuals within countries with a lower rating, it becomes increasingly challenging to borrow from overseas. Banks and investors may well seek higher interest rates to account for the perceived increase in risk.

Ghana’s government had pledged to reduce Ghana’s aid dependence, promising a “Ghana beyond aid”(5). That ship appears to have sailed and the bailout Ghana seeks from the IMF will be in the billions and this help is likely to come with significant caveats.

For ordinary citizens, IMF bailouts often come with very real consequences. In exchange for aid, governments are often required to undertake significant austerity measures in the form of mandated increases in taxes, wage freezes and widespread suspension of welfare programs.

During their visit to Ghana, the IMF delegation recognised that the issues facing Ghana are in no way unique, but are symptomatic of an “increasingly difficult global environment”(6).

Sri Lanka is currently experiencing its most significant financial crisis in over 70 years and will likely need significant international help, while Bangladesh has also sought urgent investment, including seeking loans from the IMF, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank(7)

Individuals in these countries, much like those within Ghana, will feel the impact of international economic forces outside of their control and with a challenging outlook for the global economy, things may well become harder before they get easier(8).