Europe’s security environment is undergoing a profound transformation. In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and diminishing US strategic focus on the continent, European nations are increasingly diverting funds from productive sectors of the economy such as education, healthcare, business development, and infrastructure towards military expenditures and defence build-up. This is not necessarily unjustified. IEP analysis suggests that the primary issue for Europe is less about expenditure and more about coordination. That is to say, the continent should be less concerned about increasing spending and more focused on effectively overcoming its structural fragmentation in its defence forces to build cohesive and efficient defence capabilities.

Focusing disproportionately on military expenditure could undermine the very stability that defence aims to protect. True security depends not only on tanks and fighter jets but also on social cohesion, economic opportunity, and public trust in institutions. A militarised Europe that fails to address these internal pressures may become less secure, not more, risking increased social fragmentation and polarisation, which would in turn sap political resolve to meet common external threats. A greater focus on a country’s international security can come at the expense of its domestic stability and security. It’s a delicate balancing act.

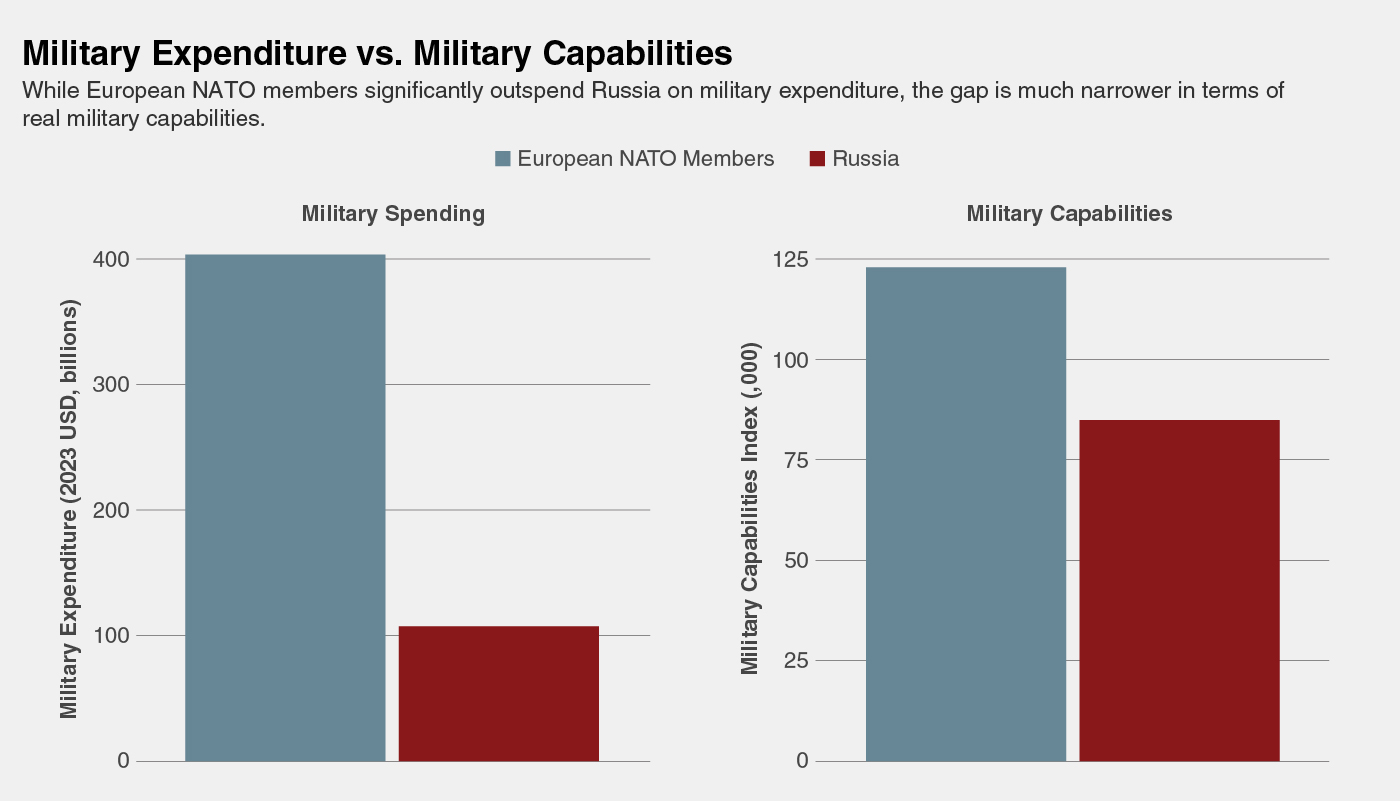

At face value, Europe appears to have the upper hand. NATO members in Europe outspend Russia on defence by a large margin. But this comparison, often illustrated using market exchange rates, obscures important realities. First, such figures do not consider purchasing power parity (PPP). In countries like Russia, where personnel and administrative costs are lower, a dollar can buy significantly more than it can in advanced economies. Western defence budgets, particularly in Europe, often allocate a substantial portion to salaries, pensions, and other non-combat costs. As a result, the nominal advantage in spending by Europe may exaggerate the real disparity in effective military spending and investment. It is worth noting that the values reported here reflect realized military spending and exclude long-term increases announced by European countries since the start of the Russia–Ukraine war in 2022 that have yet to materialize.

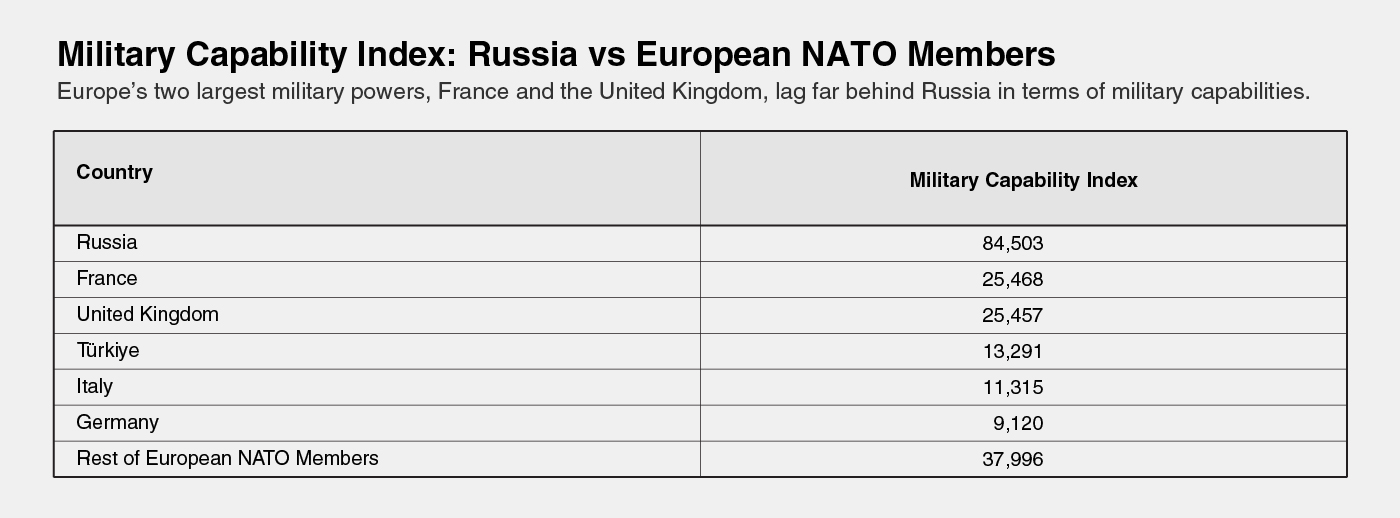

Spending, however, is only part of the equation. What truly matters is how efficiently resources are translated into usable military power. IEP has estimated real military capability through a framework that evaluates both the quantity and quality of a country’s military assets, along with battlefield experience and combat readiness of its armed forces. When seen through this lens, the gap between Russia and the combined European NATO members is far narrower than spending figures suggest. Given its involvement in the largest conflict in Europe since World War II, Russia’s battlefield experience and combat readiness surpass those of any European NATO member.

Moreover, no individual European country comes close to Russia’s military capability. Even France and the United Kingdom, Europe’s two most capable militaries, have less than a third of Russia’s overall capacity. Strikingly, despite sustaining heavy losses in Ukraine, Russia has increased its overall military capability since 2022. Over the past three years, it has lost a considerable portion of its armored vehicles, a large number of fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft, and more than half of its Black Sea naval fleet. Its ability to recover from these losses highlights a massive diversion of funds toward military expenditure and a sustained commitment to maintaining an outsized military force.

The key question for Russia is the sustainability of its current level of military expenditure. As the country pivots toward a war economy, its nominal GDP has declined by 12 per cent to $2 trillion. When measured in purchasing power parity (PPP), Russia’s economy is estimated to remain flat at around $6 trillion between 2022 and 2024. In contrast, the combined PPP-adjusted economies of France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany total approximately $17.5 trillion. Over the longer term, this may evolve into an economic war of attrition, with Russia increasingly consuming its domestic economy to sustain its war effort.

Europe’s real challenge lies in the absence of integration. Despite collectively outmatching Russia, European forces are hindered by fragmentation. Defence policies, procurement systems, and command structures remain predominantly national, leading to large-scale inefficiencies. NATO has long depended on American leadership, intelligence sharing and logistical infrastructure. With uncertainty around continued US commitment, European nations face mounting pressure to coordinate their defence capabilities. Yet without unified strategic vision and an integrated command, Europe’s defence potential will remain unrealised. The efficiency and integration of its fighting forces are currently more important than increasing its absolute level of military expenditure.

Finally, nuclear deterrence remains a significant strategic gap. At present, Russia possesses over 1,700 active nuclear warheads, while France and the United Kingdom maintain a combined arsenal of approximately 400. Although both stockpiles have the destructive capacity to devastate the planet multiple times over, expanding these arsenals is not a viable solution. The most pressing question is not one of capability, but of intent—whether any side would ultimately be willing to use such weapons.

Complicating matters further are the socioeconomic trade-offs of increased defence spending. Allocating more funds to the military often means diverting resources from essential areas like business support, health, education, and welfare, or increasing public debt and taxation. Europe is already grappling with low productivity growth, a rising cost of living, and the surge of populist movements that thrive on economic discontent. Escalating military budgets in this context risks fuelling societal divides.

Europe’s current push toward greater militarisation is not unwarranted, but it must be strategic. Simply increasing budgets will not address the most pressing issues: lack of integration, and the political-economic risks of neglecting domestic priorities. For Europe to truly strengthen its internal and external security, it must focus on building an integrated defence force while carefully balancing military needs with the wellbeing of its citizens.