As demographic transitions accelerate, humanity is entering a period unlike any before. The 2025 Ecological Threat Report examines how changing population dynamics intersect with ecological pressures – resource scarcity, environmental degradation, and climate vulnerability – to shape global resilience.

For much of recorded history, the human population has grown steadily, driving social development but also intensifying demand for land, water and food. The coming century, however, will mark a profound tipping point: global population growth is projected to slow substantially, peak, and ultimately contract.

While a stabilising population may ease strain on ecosystems, an ageing society and shrinking workforces introduce new vulnerabilities. As populations age, a shrinking working-age population will need to sustain the growing needs of older communities, increasing economic strain and dependence on the working class. Any lapses in efficiency could exacerbate these pressures, leaving societies more vulnerable to economic fluctuations and external shocks.

Declines in productive-age populations will test economic systems already burdened by inequality and environmental stress. Without proactive adaptation – in governance, labour, and health care – these demographic shifts could amplify fragility rather than resilience.

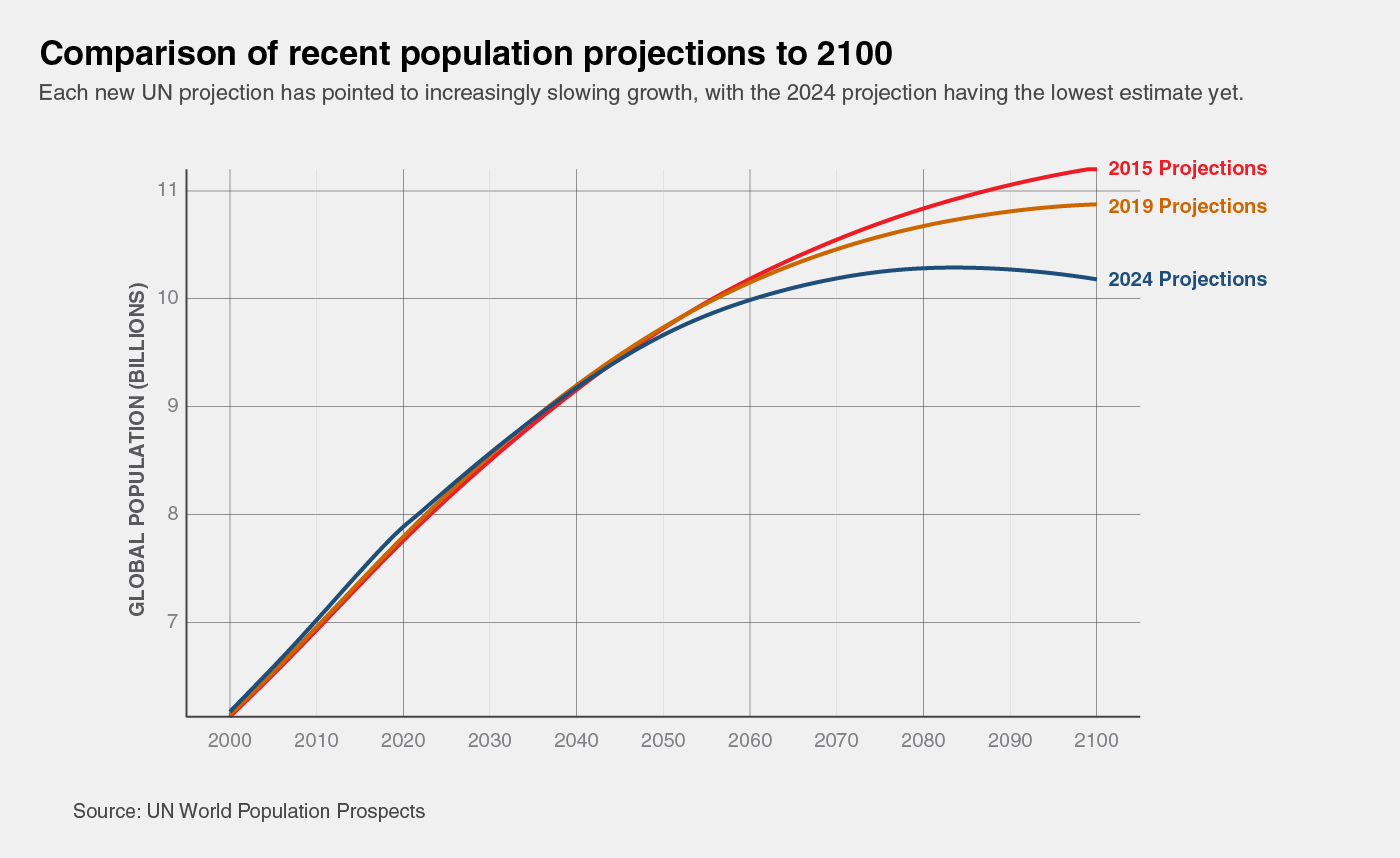

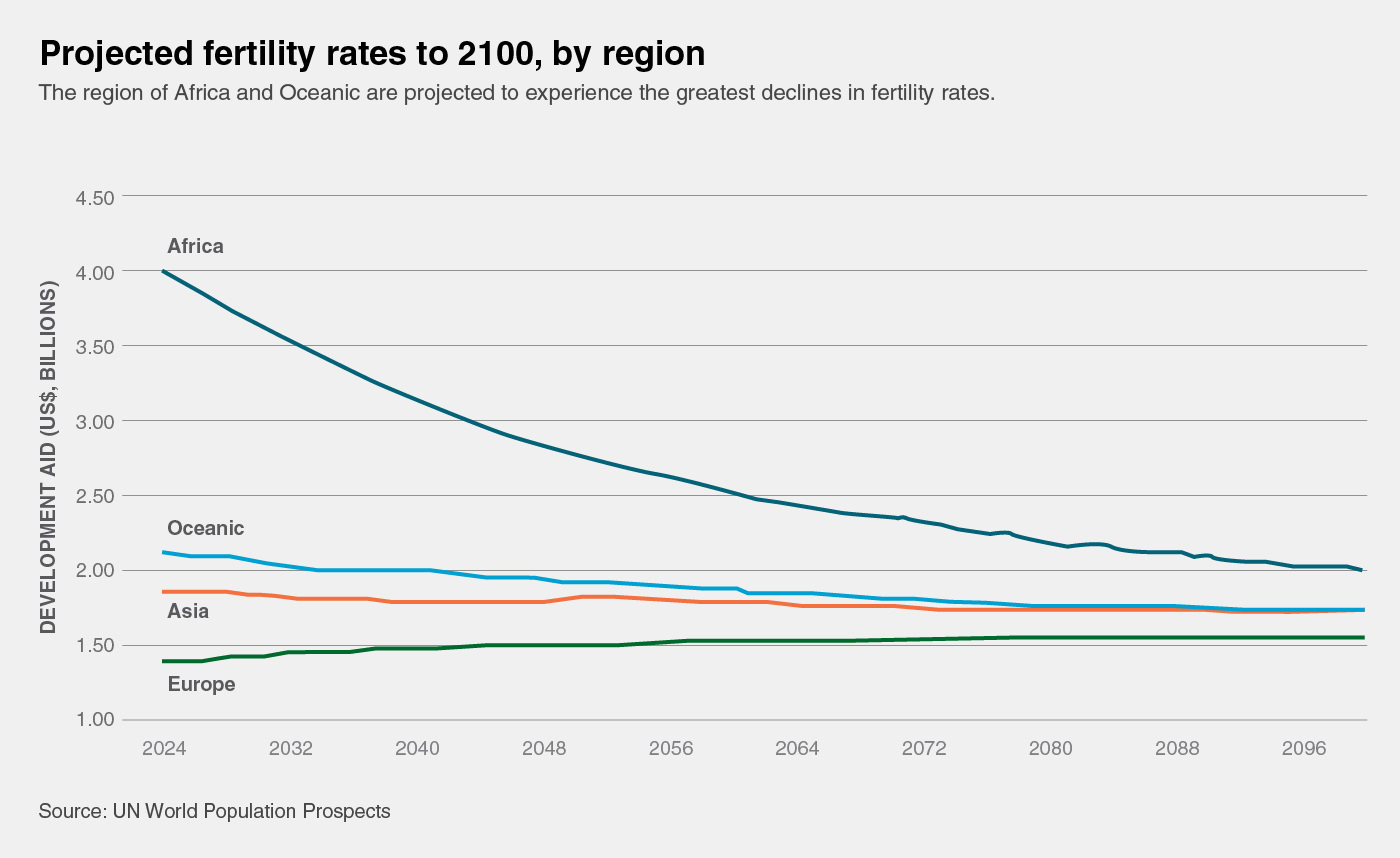

According to the United Nations World Population Prospects 2024, the global population is expected to peak at approximately 10.3 billion in 2084, before declining slightly to around 10.2 billion by the end of the century. The report anticipates that the global fertility rate will fall below the replacement threshold of 2.1 births per woman by 2050, a historic demographic shift.

Population projections have been revised downward over the past decade, driven largely by faster-than-expected declines in fertility rates, particularly amongst many African, Asian, and Pacific countries.

This deceleration has been driven by rapid urbanisation, changing social norms, and expanded access to education and family planning. While these developments reflect human progress, they also reshape the foundations of economic and social stability. Urbanisation has raised the costs of housing and schooling, making large families less practical and adding financial pressure on parents. Without sustained economic growth and rising real wages, many households postpone childbearing to later ages. Social change has reinforced these structural pressures. In many developed countries, longer periods in education and early-career investment have been prioritised over early marriage and first births, further shortening reproductive windows.

At the same time, cultural norms have evolved. Deliberate policy interventions, including national family planning programs, have helped normalize smaller family units and foster greater acceptance of remaining child-free. The widespread availability of safe, effective contraception has enabled people to act on these preferences, translating new norms and life-course priorities into sustained declines in family size.

Fertility decline has substantially slowed global growth rates: from a peak of 2.3 per cent in 1963 to just 0.8 per cent in 2024. Growth is expected to turn negative in 2085, with the global population contracting by around 0.13 per cent annually by the end of the century.

Regional disparities in population trajectories remain stark. Sub-Saharan Africa continues to experience the highest growth rates globally, even as fertility falls sharply. Niger, Uganda, and Malawi are projected to nearly double their populations by mid-century, intensifying pressure on essential resources. By contrast, East Asia and Eastern Europe face rapid contraction, with countries such as China, Japan, and Russia expected to experience population losses that challenge fiscal and social systems built on sustained growth. Collectively, the ten countries projected to contract most will lose nearly 150 million people by 2050.

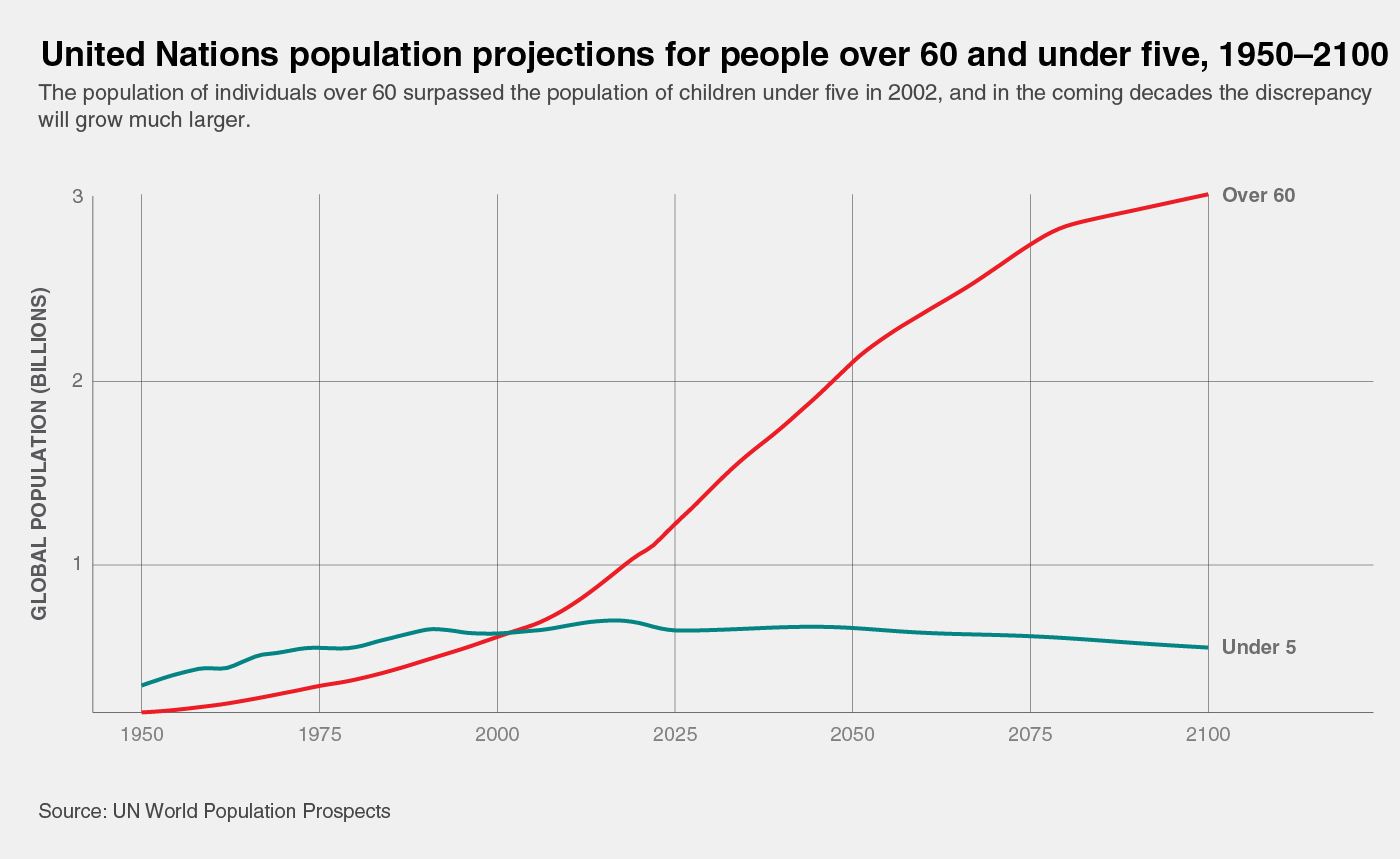

While slowing or negative growth may ease ecological pressures, it may also challenge the capacity of societies to meet communal and economic needs. Ageing societies will contend with shrinking labour forces, rising old-age dependency ratios, and mounting demands on health, pensions, and public services. By the 2050s, older adults will far outnumber children, reversing a demographic balance that has persisted for centuries.

Despite a slowdown in overall growth, the number of people aged over 60 is projected to rise throughout the century, eventually surpassing three billion. By then, global life expectancy is estimated to reach nearly 82 years, an increase from 73 years in 2024. Longer life expectancy, a triumph of human development, will nonetheless require rethinking models of productivity, health care, and social cohesion.

Japan’s demographic transformation exemplifies this inverted population pyramid, with nearly a third of its citizens now 65 or older, the oldest population globally. With one of the world’s highest life expectancies and lowest fertility rates, the nation now faces a dependency ratio (seniors per working-age person) of roughly 50 seniors per 100 adults, underscoring the economic and social strain that accompanies rapid ageing.

Moreover, since the 1990s, the working-age share of the population has declined by roughly 11 per cent. This rapid aging places mounting pressure on Japan’s pension and healthcare systems, which rely on a robust labour force to sustain funding. By 2040, the country may face a shortfall of up to 11 million workers, posing serious risks to economic growth and fiscal stability as labour shortages outpace government policy interventions.

Demographic change is reshaping the global landscape in divergent ways. Rapid growth in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will amplify stress on food, water, and infrastructure, while contraction and ageing in East Asia and Eastern Europe, will test economic resilience and social protection systems. With faster-than-expected declines in fertility rates disrupting national strategies designed to manage anticipated demographic transitions, countries face an increasing risk of sudden demographic crises that could undermine ecological sustainability, social stability, and global security.

As global demographic momentum shifts, policy responses must be anticipatory rather than reactive. Population trends alone do not determine human outcomes – but they set the parameters within which resilience must be built. Recognising the shared stakes of demographic change is essential for crafting cooperative solutions that safeguard both communities and our planet in the decades after the peak.

— Download the Ecological Threat Report Press Release

— Request a Media Interview

— View the Ecological Threat Report Interactive Map

— Further reading: Extreme Wet-Dry Seasons Emerge as Critical Conflict Catalyst