The 2025 Ecological Threat Report (ETR) finds that South Asia remains one of the world’s regions of greatest ecological strain. Among the four inter-locking threats analysed – water risk, food insecurity, demographic pressure and the impact of natural events – water emerges as both a driver of vulnerability and an area where cooperation has prevented conflict.

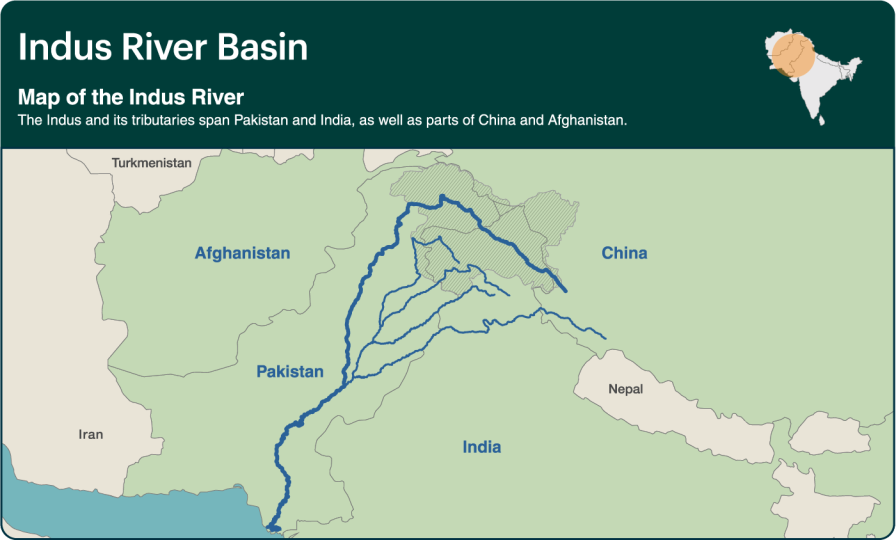

India and Pakistan illustrate this dual reality: two nuclear-armed neighbours whose shared dependence on the Indus River has, for six decades, been governed by an agreement that has outlasted wars, political upheavals and climatic shocks.

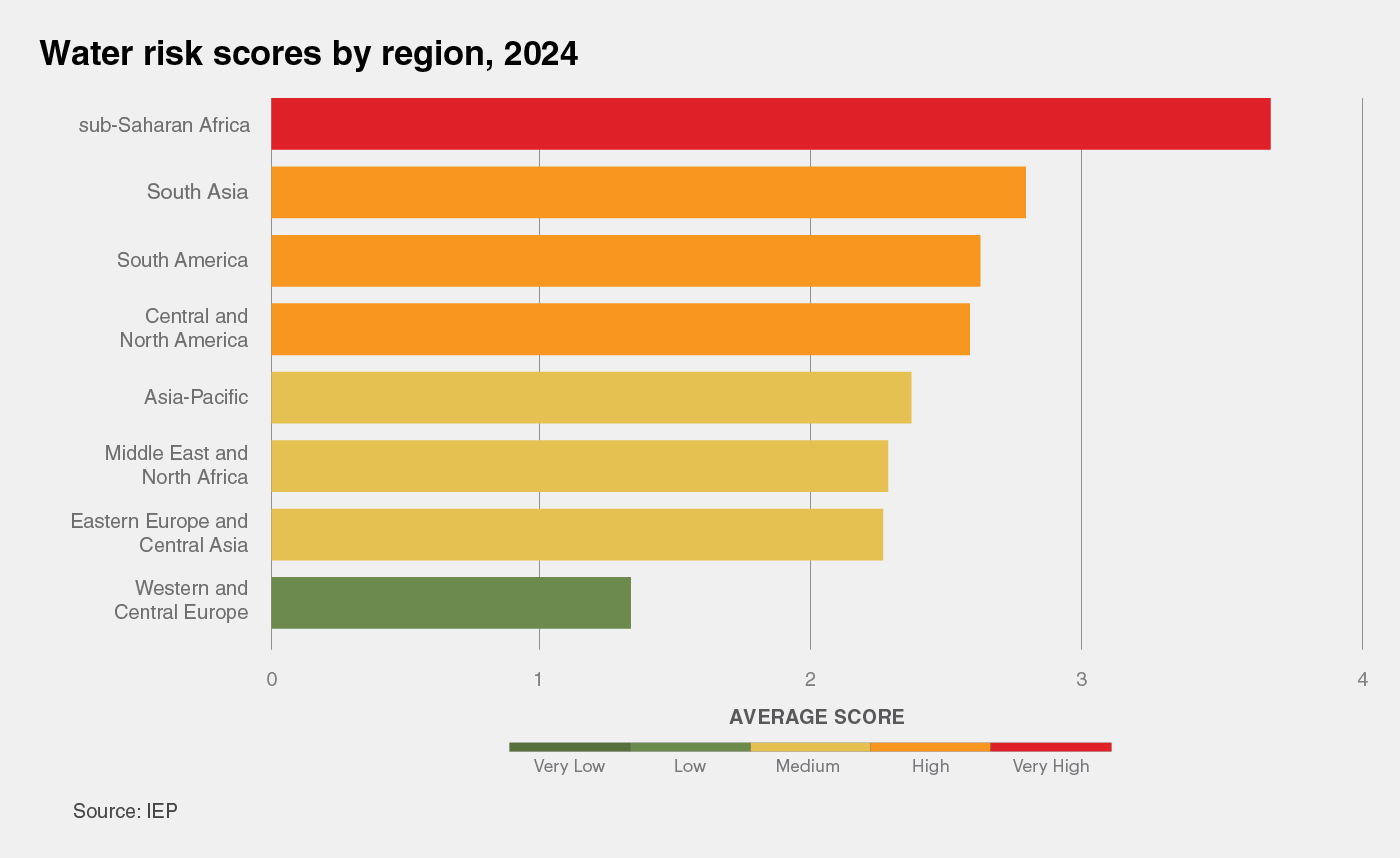

Across South Asia, ecological risks linked to water are intensifying. The ETR identifies the region as facing the second-highest overall ecological threat globally, with particularly high scores for water risk, food insecurity and exposure to natural events. Rapid population growth, urbanisation and expanding agricultural and industrial demand are combining to reduce per-capita freshwater availability even though total rainfall remains relatively constant.

Since 1950, global freshwater supply per person has fallen by about 70 per cent as population has tripled, and South Asia is among the most affected regions. Annual withdrawals appear to have peaked around 2019, but the region’s fast-growing populations continue to drive higher demand. In India and Pakistan, this imbalance is amplified by reliance on major river basins and rapidly depleting aquifers.

Groundwater provides drinking water for more than two billion people worldwide, and roughly 70 per cent of withdrawals are used for agriculture. The ETR notes that five of the world’s most over-extracted aquifers, including the Ganges and the Indus Basin, are in South and East Asia. Collectively, these systems support nearly one billion people, with the Indus Basin alone providing water for about 90 per cent of Pakistan’s food production. This dependence exposes both nations to mounting risk as groundwater is drawn down faster than it can be replenished.

The ETR identifies 295 sub-national areas with very high water risk and a further 780 with high risk, affecting almost 1.9 billion people globally. South Asia accounts for a large share of this total. While access to safely managed water has expanded markedly since 2000, short-term variability in rainfall and chronic groundwater depletion continue to undermine stability.

Agriculture dominates regional water use. The report finds that irrigated land, which equates to about 20 per cent of global cropland, produces 40 per cent of the world’s food. In densely populated South Asia, this dependence is even greater. Climate variability and erratic monsoons therefore pose direct threats to food security. Afghanistan, the region’s most water-stressed country, records one of the highest water risk scores worldwide; India and Pakistan face medium-to-high risk at the sub-national level.

The ETR links rainfall seasonality, or the tendency for rain to fall in fewer, more intense bursts, to rising conflict risk. Globally, areas where rainfall is becoming concentrated into shorter wet seasons record conflict death rates more than 50 per cent higher than regions where rainfall seasonality is decreasing. The effect is strongest where ecological fragility intersects with fast population growth and limited freshwater access. In parts of South Asia, these conditions coincide, heightening the potential for competition over land and water.

Against this background, the Indus River system remains a rare example of enduring cross-border collaboration. The ETR describes the Indus Waters Treaty between India and Pakistan as a “core conflict-resolution tool and point of cooperation for 60 years”. Even after repeated military confrontations, water-sharing has continued. This continuity underscores a central conclusion of the report: that strategic cooperation, when institutionalised, can outweigh the risks of confrontation.

The treaty’s durability rests on clear allocation of river flows, joint management institutions and mechanisms for dispute resolution. It has allowed both countries to plan large-scale irrigation and hydropower projects, supporting the livelihoods of hundreds of millions. In 2025, India’s temporary suspension of the treaty marked a period of heightened political tension, but the ETR emphasises that outright interstate war over water remains unprecedented in the modern era. Globally, 157 international freshwater treaties were signed in the second half of the 20th century, reflecting an understanding that large-scale disruption of water flows would carry “catastrophic ecological and human costs”.

The ETR draws an instructive parallel between cooperation on water and restraint in nuclear policy. As with weapons of mass destruction, threats to water supplies create mutual vulnerability. Recognising that collapse of shared river systems would devastate both sides, neighbouring countries have chosen pragmatic collaboration over escalation. This pattern is observed not only in South Asia but also in other transboundary basins, such as the Senegal and Sava Rivers, where principles of joint ownership and equal decision-making have turned potential flashpoints into mechanisms for stability.

For India and Pakistan, shared dependence on the Indus Basin exemplifies this logic. Roughly 44,000 cubic kilometres of renewable water are generated globally each year through rainfall and snowmelt, feeding rivers and aquifers. While the total supply is relatively constant, per-capita availability has declined sharply, from 18,000 cubic metres in 1950 to just over 5,000 in 2025, making cooperative management increasingly vital.

The ETR concludes that water stress has historically been more likely to foster diplomacy than war, particularly where institutions exist to manage shared resources. Yet as rainfall variability intensifies, so does the need for adaptive cooperation. The report highlights the benefits of investments in micro-capture and small-scale irrigation, flexible allocation rules, and cost-sharing mechanisms that distribute both risks and benefits across communities. Such approaches can buffer rainfall shocks and sustain agricultural economies.

“Despite fears that India might weaponise its control over the headwaters of the Indus, water has continued to flow,” said IEP Founder and Executive Chairman Steve Killelea.

“Even during recent crises, when political rhetoric has hardened, neither side has acted to deliberately disrupt supply. This is not because goodwill outweighs grievance, but because both nations understand that the consequences of breaking the treaty would be catastrophic for millions of people on either side of the border.”

For South Asia, closing the gap between water availability and demand will depend on both technological and institutional innovation. Protecting groundwater recharge zones, modernising distribution networks and improving on-farm efficiency can all reduce pressure on the Indus and Ganges systems. Equally important is continued dialogue under existing frameworks such as the Indus Waters Treaty, coupled with updated data-sharing to reflect today’s hydrological realities.

The ETR finds a strong correlation between ecological threat and low levels of peace, with countries facing greater food and water stress also tend to be less peaceful. For India and Pakistan, maintaining cooperation over water is therefore not merely an environmental or developmental goal but a cornerstone of regional peace. Effective water governance reduces competition, supports livelihoods and strengthens trust, even amid broader geopolitical tensions.

In coming decades, demographic and climatic pressures will further test South Asia’s resilience. Population growth across the region will raise demand for food and energy, while glacier retreat and shifting monsoon patterns alter river flows. The ETR underscores that adaptive, cooperative management of shared waters offers one of the most practical routes to preventing future conflict.

— Further reading: Extreme Wet-Dry Seasons Emerge as Critical Conflict Catalyst