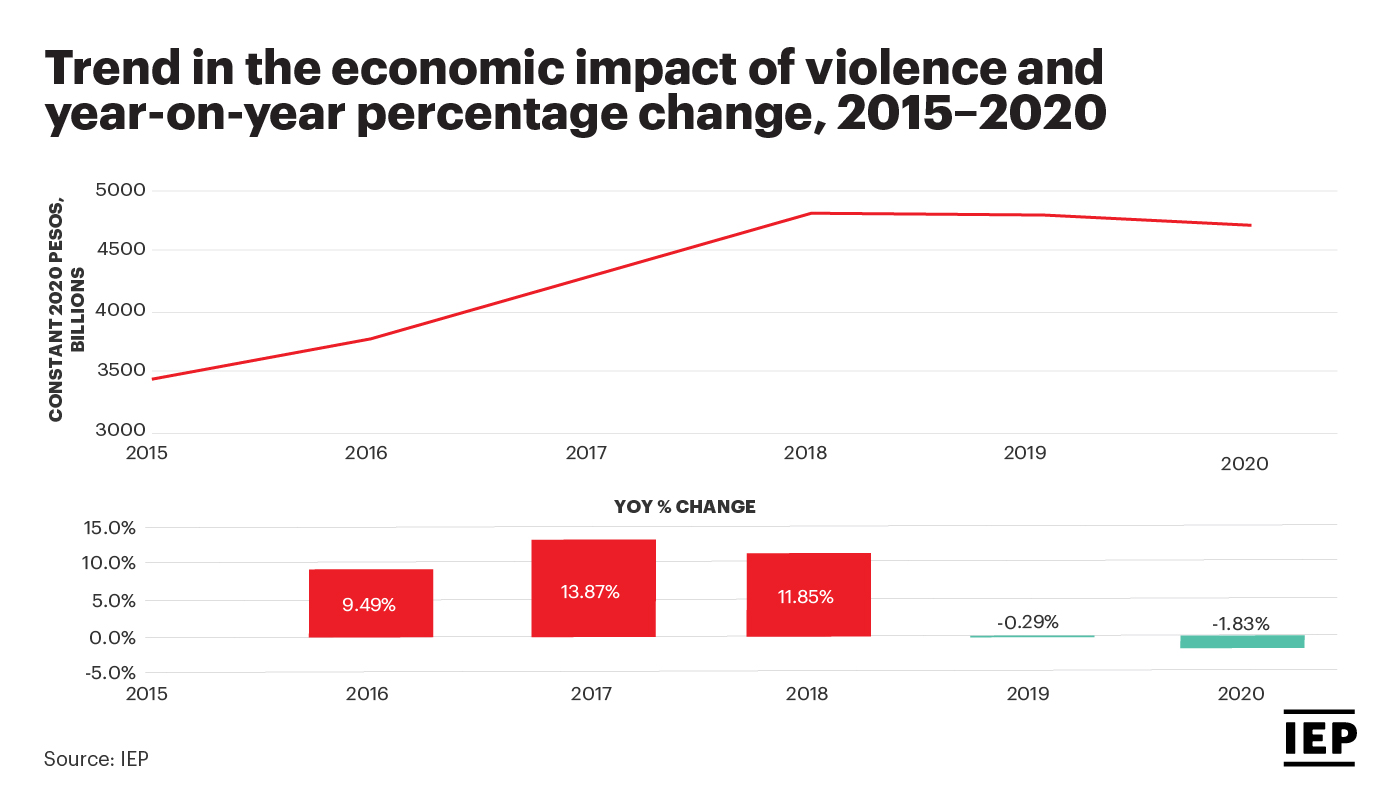

In 2020, Mexico registered a 3.5% increase in its peacefulness, a notable improvement following four successive years of decline. The shift was driven by a culmination of improvements across all Mexico Peace Index 2021 indicators, with the exception of detention without a sentence.

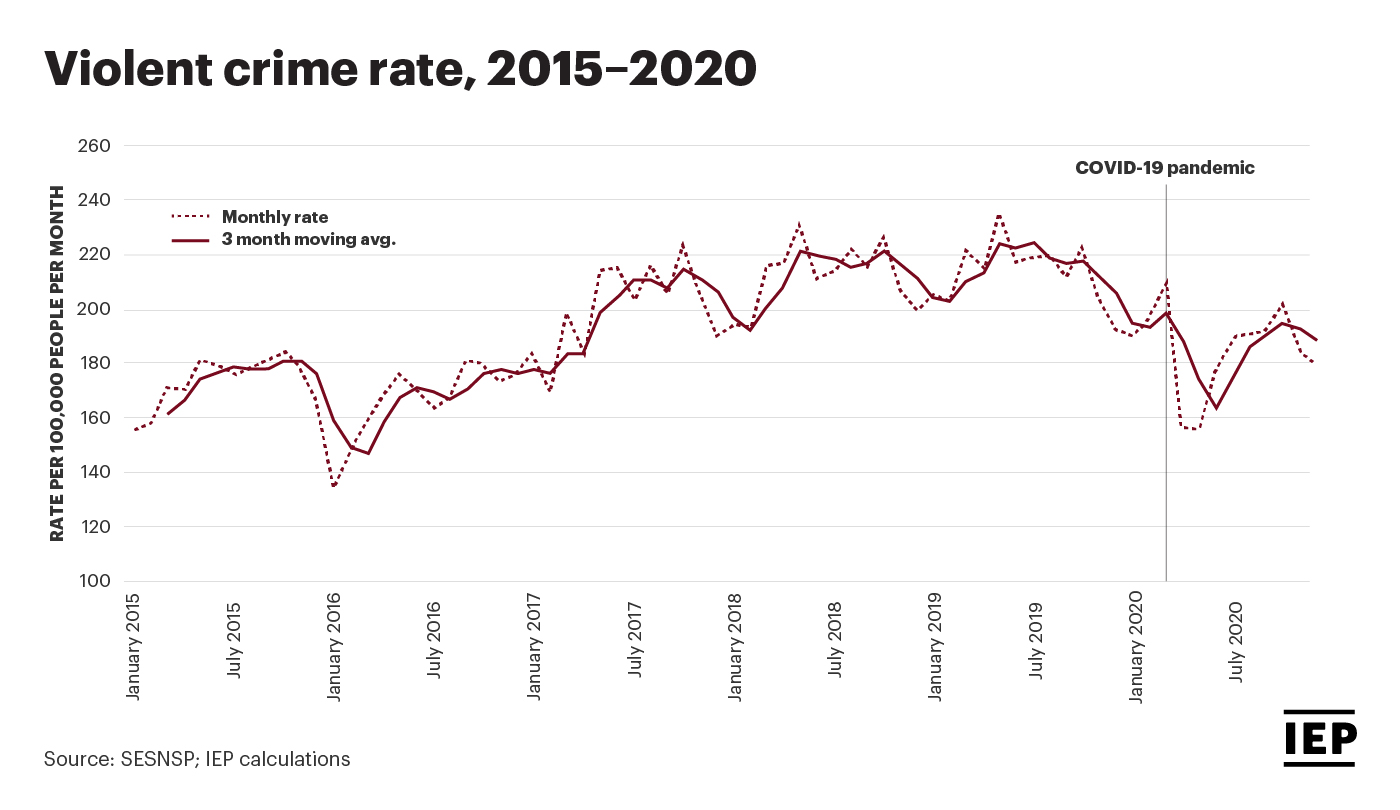

While the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent stay-at-home orders played a significant role in disrupting illegal activity and violence in Mexico in 2020, most indicators from the Mexico Peace Index 2021 began to see positive recoveries in the six-month period preceding the pandemic.

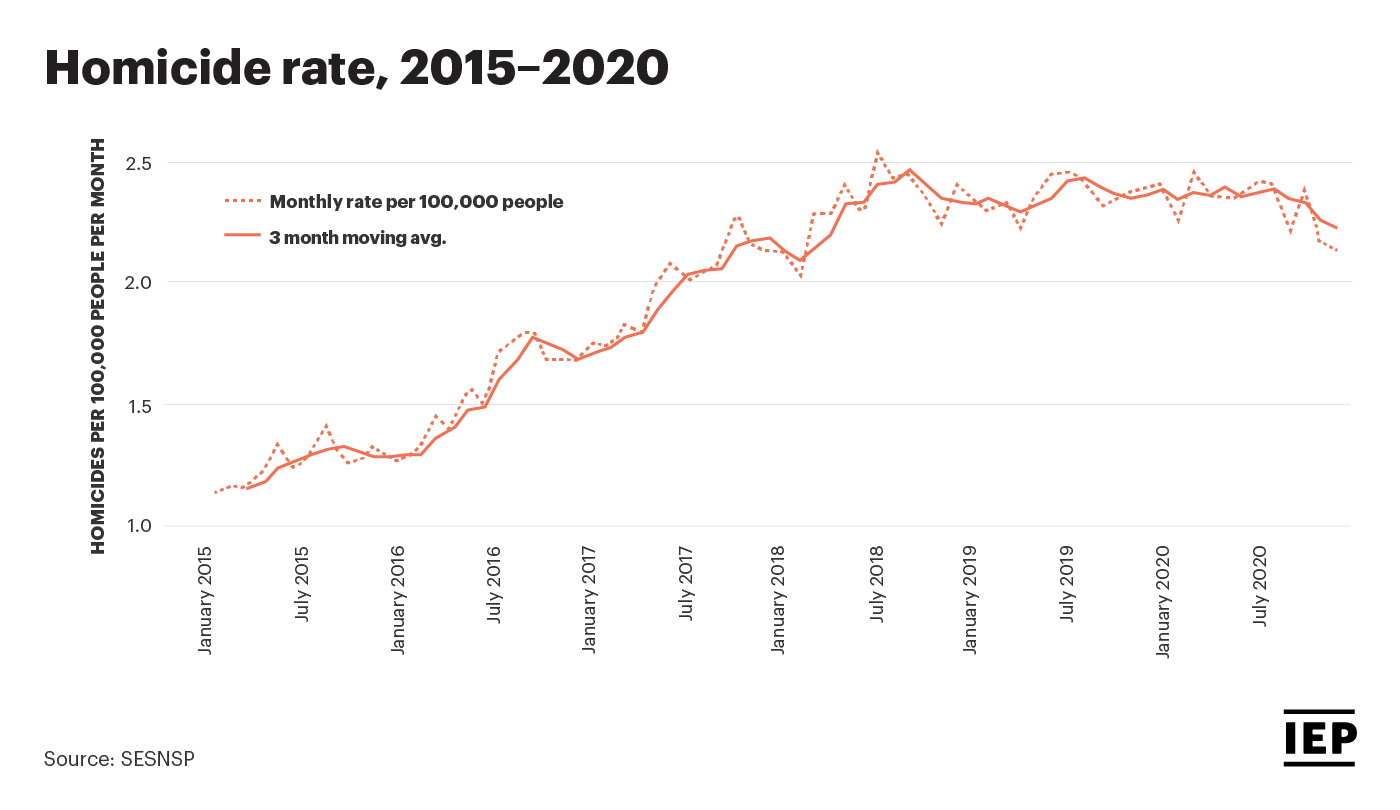

Notably, 2019 registered a 1.8% increase in the homicide rate, which represented a marked slowdown compared to the double-digit increases in homicides registered in the preceding four years in some of the violent states in the country.

The drivers behind these shift are complex, but critical to understanding Mexico’s path towards peacefulness in a post-pandemic environment.

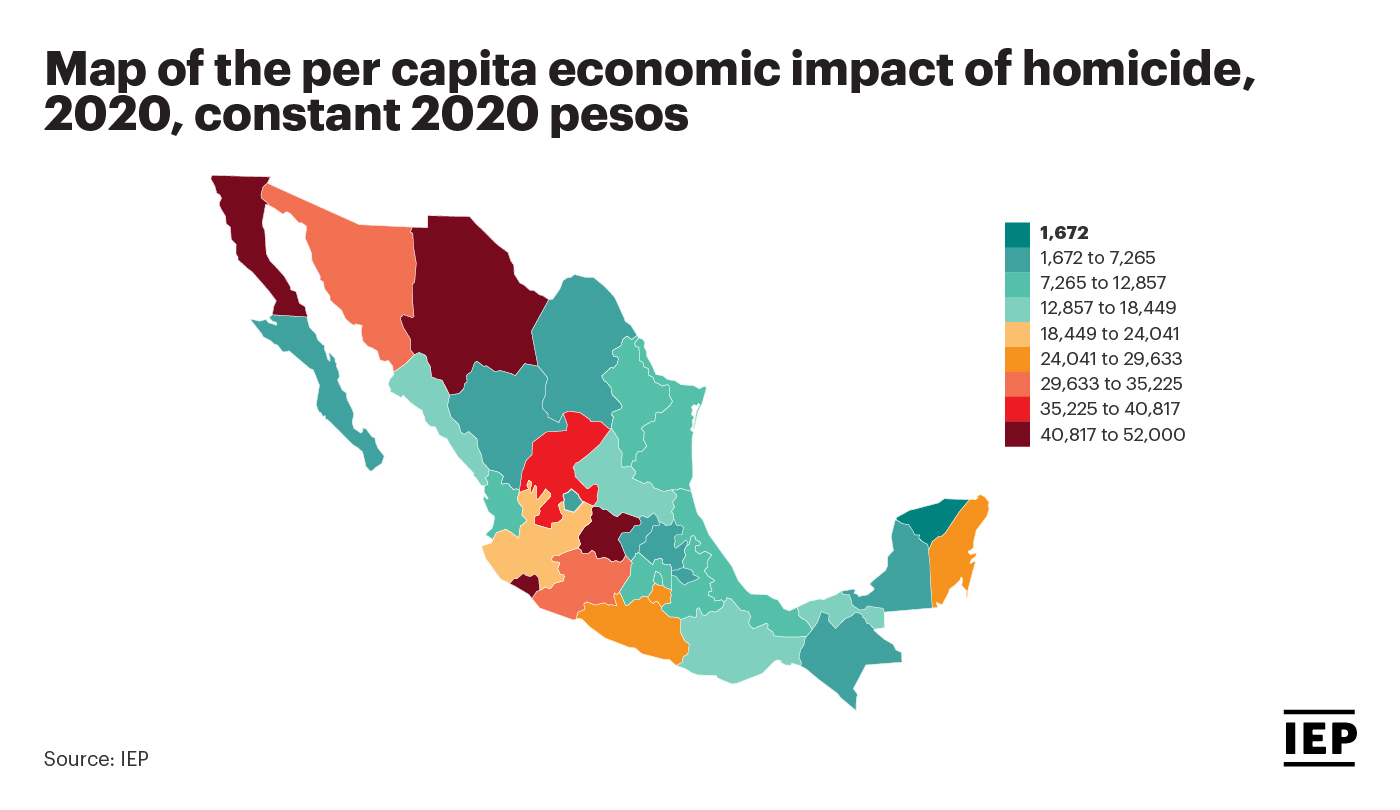

From 2015 to 2019, Mexico saw deteriorations in peace in 25 of its 32 states, underpinned primarily by an 86.5% rise in the country’s national homicide rate and a 43.4% rise in the rate of organised crime.

Over this period homicide rose to become the leading cause of death for youth in Mexico, with more than a third of total homicide victims being between the ages of 15 and 29.

As detailed in the 2020 MPI, violence in Mexico is best examined in four distinct forms, these being cartel conflict, political violence, opportunistic violence and interpersonal violence. Of these four categories, both cartel conflict and political conflict experienced slowing deteriorations in 2019.

While official crime data in Mexico does not currently distinguish violence relating to organised crime and violence from other causes, third party estimates indicate that roughly two-thirds of the country’s homicides can be connected to organised crime.

The driving force behind increased cartel bloodshed is the increased fragmentation of Mexico’s criminal organisations.

While government-cartel conflict has been an enduring feature of Mexico’s history, the escalation in military-led crackdowns under President Felipe Calderón in 2006 is typically viewed as an inflection point in violent conflict and the beginning of the Mexican drug war.

This period saw a rapid fragmentation of criminal organisations, as Mexico’s military ramped-up arrests and execution of the leaders of major cartels. Disruptions to the leadership of these organisations created power vacuums and internal conflicts, which fuelled an exponential growth in bloodshed.

Where the pre-2006 period in Mexico saw illicit activity channelled through only three criminal organisations — the Sinaloa Cartel, the Tijuana Cartel, and the Gulf Cartel — the following 14 years saw 42 criminal organisations and splinter groups appear.

The relative decline in homicides from mid-2018 can be attributed in part to realignments in the country’s organised criminal landscape and significant territorial consolidations between larger cartels.

Notably, the states that recorded the largest reductions in homicide since mid-2018, were also the regions that registered sharp declines in the number of armed clashes between rival criminal groups over the last two years.

A reduction in political violence was also a contributing factor to the overall shift towards peacefulness observed across Mexico in 2019. However, since the end of 2020, political violence has been on the rise again, in the lead up to Mexico’s mid-term election.

Political turnover has a long-standing relationship with increased rates of violence in Mexico.

It is argued that the country’s criminal organisations establish modes of coexistence and cooperation with governments over time, relationships that create a relative stability in criminal activity.

Changes in political leadership can disrupt these connections and drive uncertainty and competition in the criminal landscape.

The resulting conflict can be observed in the period surrounding the 2018 Mexican General Election, the country’s most violent since the 1910 presidential contest that sparked the 1910-1920 Mexican Revolution.

From September 2017 to August 2018 a total of 850 instances of political violence were recorded across Mexico, a period that captures the ten-month period preceding the election and the two months of political transition that followed.

June 2018, the month of the election, saw the peak of this violence with 30% of annual attacks occurring over the 30-day period.

Around 81% of recorded instances of political violence were targeted at opposition candidates, an imbalance that suggests that perpetrators were likely either aligned with the incumbent political party or found the incumbent’s policies preferable to the opposition’s.

As Mexico settled into its new political regime lead by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, 2019 saw a reduction in political violence.

By late 2020, political assassinations began to increase again with the beginning of the election process in September. At least 139 politicians, government officials and candidates were killed between September 2020 and March 2021.

The culmination of cartel consolidation and a brief reduction in political violence drove improvements in Mexico’s peacefulness, trends that were accelerated into the pandemic era.