Media reports and US official figures show that the influx of Central American migrants into the US are growing, with more migrants coming from these countries in the first four months of this year compared to all of 2018.

Friday 21 June, 2019: This week, US President Trump announced plans to cut hundreds of millions in financial aid to Central America, affecting countries such as El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

The US says these countries have not done enough to stop the increasing flow of migrant caravans to the US. In response, Trump plans to halt more than $400 million in aid.

Media reports and US official figures show that the influx of Central American migrants into the US are growing. More migrants are coming from these countries in the first four months of 2019 compared to all of 2018.

However, long-term data shows that the number of total apprehensions on the US-Mexico border fell sharply since the year 2000. The United Nations says the number of people fleeing for their lives from Central America grew ten times in the past five years.

Yet, the impacts of the issue are found in Mexico where around 90% of asylum-seekers seek refuge.

Data from the Global Peace Index 2019 shows that levels of peace in Central America are deteriorating.

All three regions in the Americas recorded a deterioration in peacefulness in the 2019 GPI, with Central America and the Caribbean showing the largest deteriorations, followed by South America, and then North America.

All three regions faced increasing political instability. This was exemplified by the violent unrest seen in Nicaragua and Venezuela, and growing political polarisation in Brazil and the United States.

Central America and the Caribbean had the largest deterioration, especially in Safety and Security due to widespread crime and political instability.

Central America and the Caribbean deteriorated in all three domains of peacefulness last year. Seven countries improved while five deteriorated, but as is typical of breakdowns in peacefulness, the deteriorations were larger than the improvements.

Civil unrest, violent crime and border disputes characterised the last year in the region. Protestors have called for the resignation of presidents in both Nicaragua and Honduras.

Refugees fleeing violence in the region have congregated on Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, seeking access to Mexico and the United States.

On average, the region deteriorated because of higher levels of Militarisation and lower levels of Safety and Security. Military spending (% GDP) rose, while UN peacekeeping funding fell.

The incarceration rate increased in five countries, compared to three where it declined. Political instability also deteriorated, especially in Nicaragua, Panama and Honduras. And although it improved in five other countries, the size of the deteriorations out-weighted the improvements.

On the upside, the impact of terrorism indicator improved last year, with scores improving in seven countries and deteriorating in only two. The average score for the homicide rate, for which the region ranks worst in the world, improved based on reductions in four countries.

However, Mexico, the region’s major economy, recorded its highest homicide rate in 21 years in 2018.

Reductions in political terror in Costa Rica, Haiti and Jamaica yielded a net benefit for the region, despite the year’s tumultuous politics. Costa Rica achieved the most peaceful score possible on this indicator in 2019. However, the situation deteriorated in Honduras, Guatemala and Cuba.

Nicaragua had the largest deterioration in the 2019 GPI after backsliding on nine indicators. These indicators include violent crime, incarceration, political instability, and intensity of internal conflict, resulting in a fall of 53 places.

Peaceful protests against social security reforms were met with police violence in April of 2018. As a result, conflict between the government and opposition escalated over the following year.

At least 325 people have been killed and protestors have called for the resignation of former Sandinista leader President Daniel Ortega. President Ortega has held the office since 2006.

Economic collapse in Venezuela has drastically diminished aid to Nicaragua. Therefore forcing cuts to government benefits and eroding political and economic stability.

Guatemala and Honduras also experienced escalations in political terror and instability. The UN-backed International Committee against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) investigated Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales for corruption. As a result, Jimmy Morales targeted and sought to close down the CICIG.

Protestors and riot police clashed in Honduras in January of 2019, as unrest continued a year on from the re-election of President Juan Orlando Hernández.

The opposition, including former president Manuel Zelaya who was removed in a coup in 2009, have accused Hernández of election fraud.

Hondurans who have fled the country reported arbitrary searches and seizures by military police. Apparently they were entering the homes of political activists, although, the military denies such activities. Gang violence, violence against journalists and censorship of media remain an ongoing problem in the country.

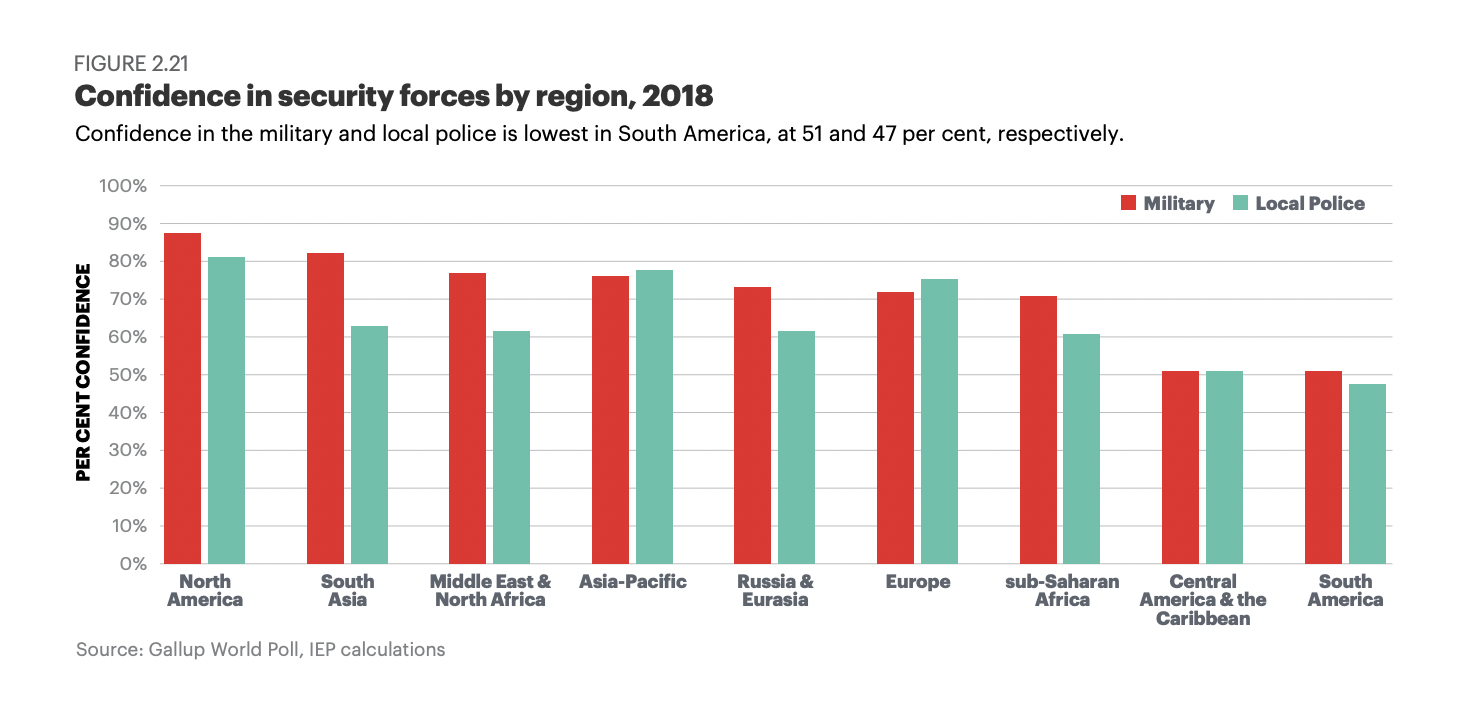

Central America shows some of the lowest levels of trust in police. What does this mean for levels of peace?

Research from the Institute for Economics and Peace demonstrates a correlation between peacefulness and confidence in the local police. The more peaceful a country, the more likely it is to have high levels of confidence in the local police force.

However, the correlation between confidence in the military and levels of peacefulness was very weak.

In Central America, Mexico and Nicaragua have the lowest confidence in local police. Only 38 and 40 per cent of respondents claimed confidence in the local police, respectively.

South America has the lowest levels of trust in police. Within South America, Bolivia and Venezuela have the lowest levels, with only 22 and 32% of respondents respectively expressing confidence in the local police.

Regionally, the highest levels of trust in state security forces are in North America.

On a global scale, peacefulness has deteriorated over the past decade. Yet confidence in both the police and military has increased on average.