The Amazon is the largest forest in the world extending into Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. This rainforest is seen as the lungs of the world; home to some of its greatest terrestrial biodiversity and equivalent in range to the biodiversity that inhabits the Great Barrier Reef.

The Amazon is home to 427 species of mammals, 1,300 species of birds, 378 species of reptiles and more than 400 species of amphibians. Despite its biocultural diversity, it is also one of the regions with the greatest ecological risk in the world according to IEP’s Ecological Threat Report.

According to the Changing Perceptions in a Changing Climate 2021 report, South America is the region with the highest concern about climate change, with more than 63% of its population seeing climate change as a serious threat. Despite its biodiversity, this territory faces the risk of becoming a desert due to increasing deforestation and global climate change. The most recent Ecological Threat Report warns about the imminent risk of water scarcity in the Amazon.

According to the Ideas for Peace Foundation, the Colombian Amazon faces an environmental crisis as well as a security crisis, as in Colombia environmental defenders face unprecedented risks. Similarly, according to Greenpeace, 33 environmental activists were murdered in 2019 in Brazil.

Recognition, as a subject of rights, has traditionally been used to refer to the human whose subjective rights are recognized and guaranteed under the scope of a social state of rights. However, the increased negative outcomes brought about by climate change, excessive exploitation of natural resources and wars have made it necessary to broaden this recognition to include ecosystems as the subjects of rights.

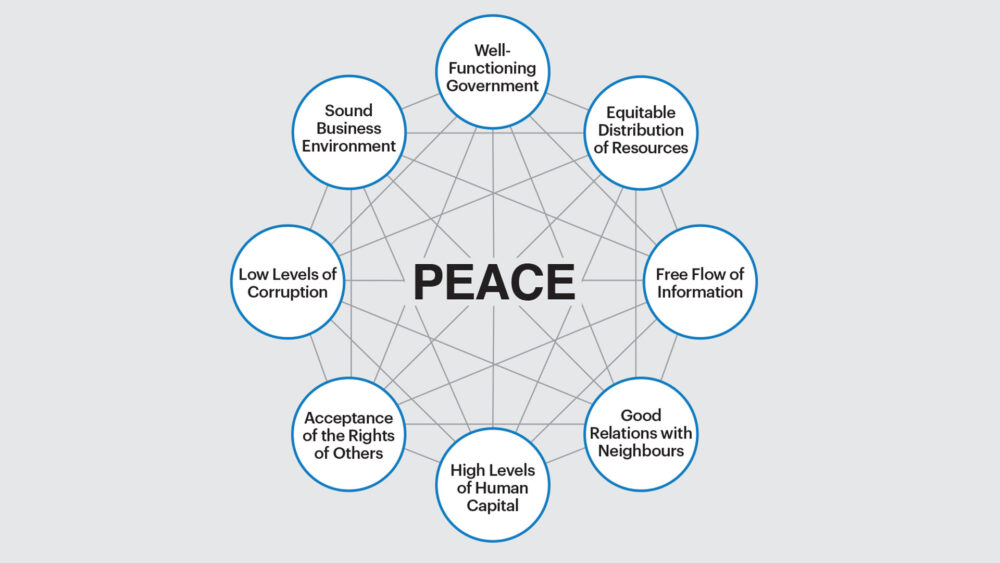

IEP’s Positive Peace pillar of the Acceptance of the Rights of Others is not limited to humans, and is fundamental to the Amazon’s conservation. Globally, there have been significant reflections recently on the recognition of ecosystems as subjects of rights.

‘Buen Vivir’ in Spanish or ‘Good Living’ in English would be the closest translation of ‘Sumak Kawsay’ from the Quechua language. According to Ecuador’s constitution of 2011, ‘Sumak Kawsay’ refers to a new form of citizenship which is in harmony with nature.

In its seventh chapter, the Ecuadorian Constitution restores the rights of nature, known by the indigenous peoples as ‘Pacha Mama’, acknowledging that it is in nature where life is reproduced and fulfilled.

Likewise, nature has the right to full respect of its existence and the maintenance and regeneration of its vital cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes. In this way, any person or community is able to demand that the public authority comply with the rights of nature.

The recognition of the Amazon as a subject of rights in Colombia has been a long process. Central milestones have included the ruling of the Council of State in 2013 recognising the rights of animals and other forms of living beings. Later, in 2015 the Constitutional Court recognized nature as a subject of rights.

In 2018, with the historic ruling 4360-2018, the Amazon was finally recognized as a subject of rights for the valuable ecosystem services that they offer to all forms of life that inhabit this planet.

Although there is a long way to go to properly protect the Amazon, Ecuador and Colombia provide encouraging examples of the progress being made to advance the protection of this ecosystem.

These two experiences similarly model countries that have adapted the conservation of biodiversity as a function of the state, sowing the seed for more biocentric models of governance and citizenship.

Examples of how the pillars of Positive Peace could be applied to the Amazon’s conservation include:

While conservation of the Amazon may seem like an overwhelming task, the pillars of Positive Peace help identify practical steps that can be taken to bring about change and the examples of Ecuador and Colombia show significant progress is already happening.