This year’s edition of the Mexico Peace Index examines the question of political violence in the country. Our analysis reveals that the recent elections in Mexico have been associated with increased levels of violence, with the highest homicide rate recorded in July 2018 the month following the last presidential election. Nationwide, there were 3,150 deaths recorded, equivalent to 2.5 murders per 100,000 people.

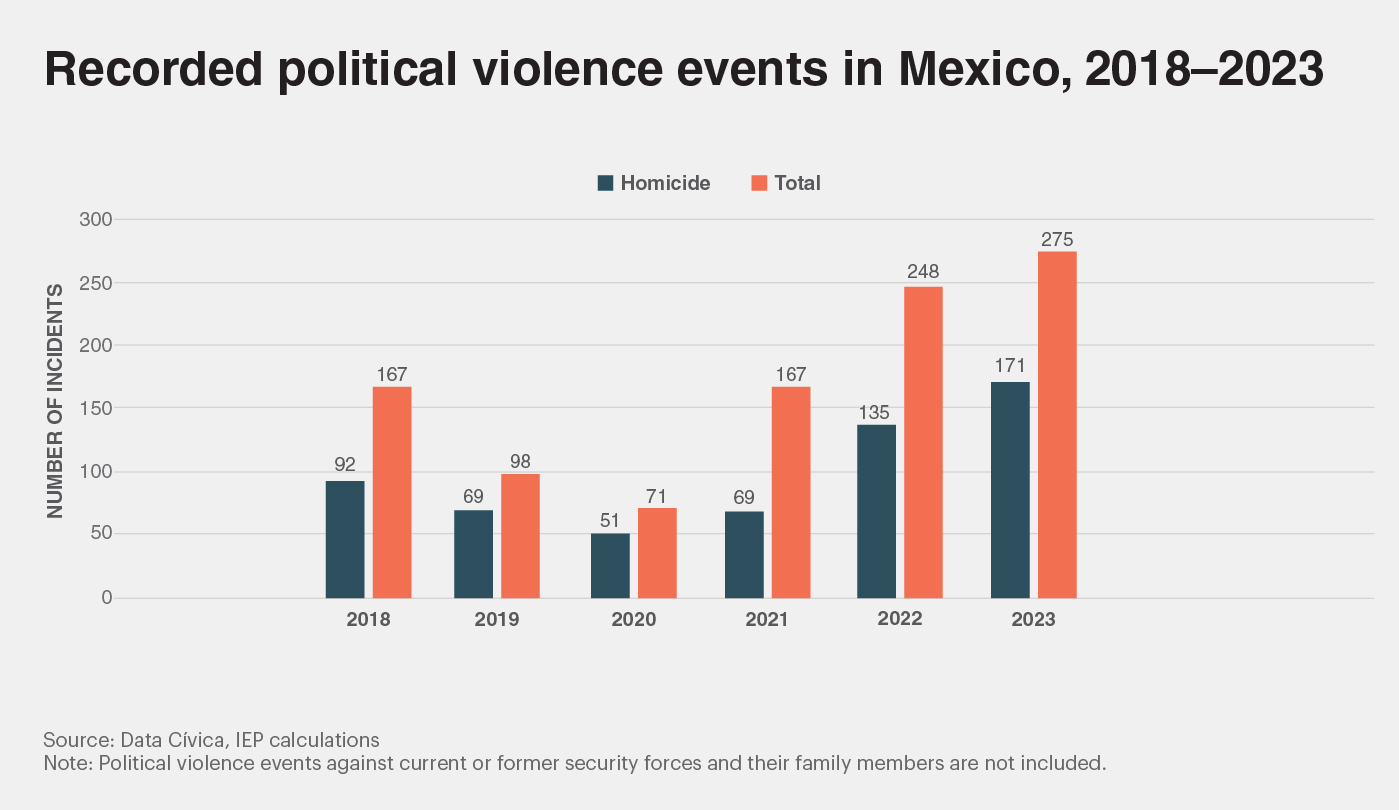

The following figure shows the annual number of political violence events in Mexico since the last major elections in 2018. According to Data Cívica records, such events include murders, physical assaults, kidnappings, disappearances and acts of intimidation. During its last presidential election in 2018, Mexico saw a high level of political violence, with 167 recorded incidents, 92 of which were homicides. Over the next two years, the recorded number of acts of violence decreased, reaching their lowest level in six years in 2020, with 71 events. However, in the last three years the number of events has been steadily increasing again. Last year the highest number on record was recorded, with 275 cases of political violence, of which 171 were homicides.

The rise in political violence in Mexico has coincided with growing political polarisation. As with many countries, there has been a growing divide in the country’s political landscape along partisan lines.

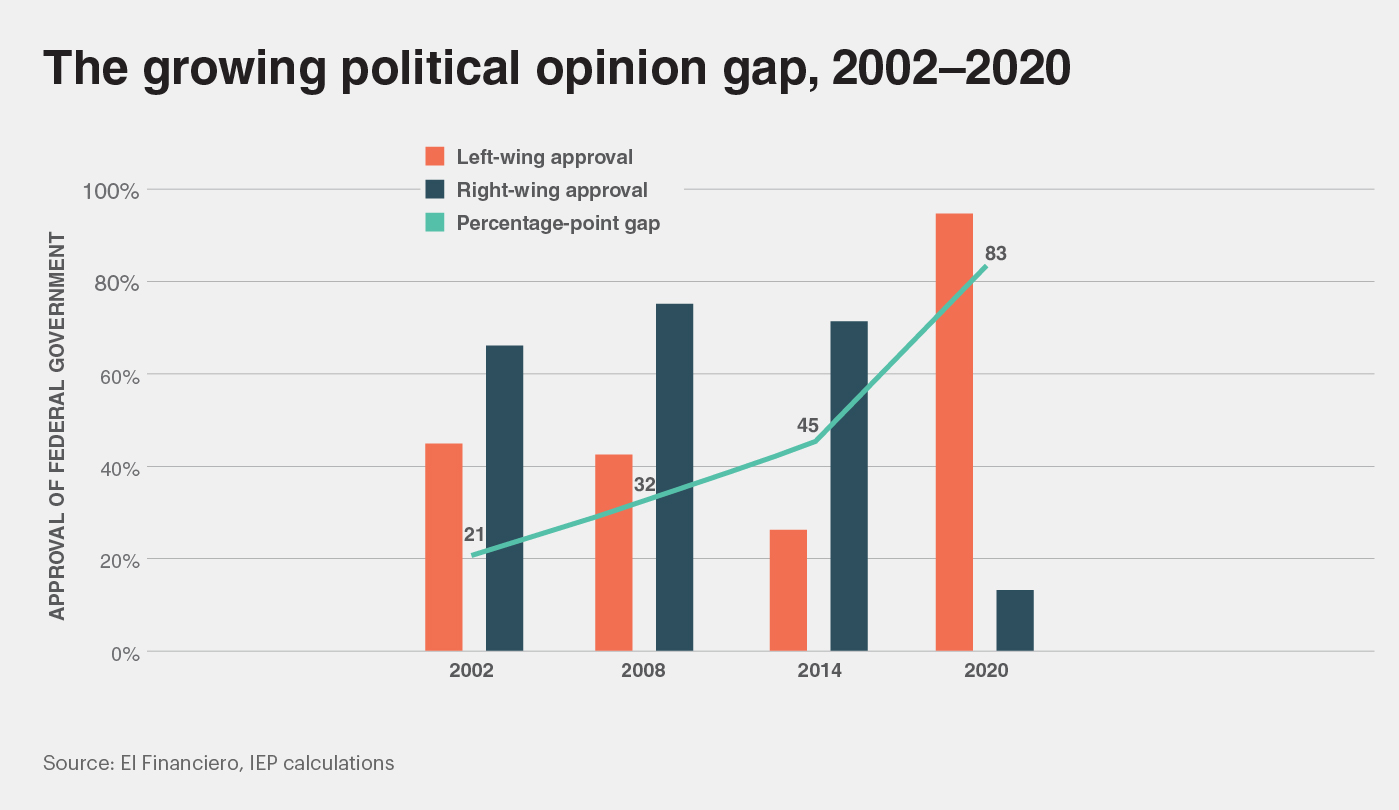

The figure below shows the results of opinion polls over the past two decades, revealing that perspectives on government have become much more polarised in that time. In 2002, the gap in federal government approval ratings between citizens who identified as left-wing and those who identified as right-wing was just 21 percentage points. That gap has since increased considerably. In 2020, it had reached 83 percentage points, a nearly four-fold increase. This indicates that people who consider themselves conservative or progressive have become much less likely to display diversity of opinion than they were 20 years ago. This has important implications for the strengthening of opinions and the willingness of citizens and officials to collaborate with those who have different political perspectives for the common good.

In recent years, polarisation has also been intensified by contentious election cycles, as well as increasingly conflicting voices within the government and the media. This latter trend has led to a more polarised media environment disseminating within the general public.

Research has also shown that political polarisation and fragmentation can exacerbate violence and undermine efforts to build peace. Organised criminal groups have been found to effectively exploit divisions in government at the local, state, and federal levels to increase their influence. A study on violence in Mexico between 2006 and 2012, for example, found that municipalities where both the municipal and state governments belonged to the same political party as the national government experienced 105 per cent less violence than municipalities aligned with the ideological opposition. More polarised states, where there are sharp divisions between rival political ideologies, tend to have weaker institutions and less social cohesion, thus contributing to more violence.

In contrast, societies that can maintain a greater degree of social and political cohesion are better equipped to contain violence and foster peace. This has largely been the case in Yucatán, which consistently ranks as the most peaceful state in the country. Research has attributed the state’s success to the ability of its political and security institutions to maintain cooperative intergovernmental relations over the past decades, even as the parties in power at the state and federal levels differed. The resulting continuity in the leadership of its security forces has contributed to permanence and cohesion within and between agencies.

Between 2018 and 2023, political violence has primarily targeted political or government personnel operating at the municipal level. Of the more than 1,000 incidents recorded, more than three-quarters have been attacks at the municipal level. Attacks against state officials, candidates, staff and their families together account for nearly a fifth of all attacks. Attacks against individuals at the federal level have been the least common, representing less than six per cent of the total.

Analysts have cited a variety of factors driving the disproportionate levels of political violence associated with municipal elections and government officials. These include the substantial importance that local power has for organised criminal groups, who tend to view control at the municipal level as central to their operations. Such motivations are suspected to have been at play in the murder of two mayoral candidates within hours of each other in the city of Maravatío, Michoacán in February 2024. In addition to using violence for political purposes, organised criminal groups have been found directly funding their favoured candidates and campaigns.

In response to the growing amount of violence, the National Electoral Institute (INE) and various federal security agencies have developed measures for candidates at risk. While the National Guard provides personnel and transport vehicles for candidates campaigning for the Senate, Chamber of Deputies, and governorships, state officials are only protected by local security forces. Both candidates running for president are under federal protection.

Candidates running for different levels of government receive different amounts of protection based on the perceived risk, with the exception of the presidency, who are protected without regard to risk. Three elements determine the risk of a candidate: incidents of crime in the states, a National Guard prepared risk analysis, and personal threats that candidates have received and reported. Those with high risk are accompanied by four official vehicles and ten army personnel, while medium risk candidates will be guarded by three vehicles and eight National Guard personnel.

Municipal politicians and candidates find themselves in particularly vulnerable positions, as local security forces are often less equipped to provide protection against heavily armed criminal groups. In addition, these individuals are much more numerous than those running for federal positions, who are also protected by federal forces. Despite this elevated risk, these candidates only receive reduced vehicles and personnel from the security secretariat. This is in addition to security personnel provided at the local level.

As the June general election approaches, experts predict that the number of political violence incidents will increase. Veracruz, Guanajuato and Morelos were among the top five states with the most political violence from 2018-2023, and all three states are scheduled to elect new governors during the 2024 elections, putting further pressure on protection services in those states.

While the implementation of safety measures is encouraging, the high levels of violence against political officials and candidates this election cycle, and over the past several years, indicates that the country still has a long way to go to safeguard those seeking public office. In addition to continuing to bolster candidate protection measures, Mexico should work to increase its levels of Positive Peace, particularly in relation to issues of corruption, as this could diminish the incentives for organised criminal groups to try to influence elections. Additionally, fostering internal cooperation will hopefully reduce the amount of polarisation within the country, lowering political tensions and the threat of violence.

For comprehensive insights into the state of peacefulness in Mexico, download and read the full report: