Key Points

For most of the postwar era, the global monetary system has rested on a simple premise: the United States issues the currency the rest of the world must use. This has underpinned US economic power and influence.

The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) describes the current era as The Great Fragmentation : a phase of heightened geopolitical tension, weaponised interdependence and weakening multilateral institutions that began around the 2008 financial crisis. Superpower influence has plateaued since around 2015, while the number of middle power countries has nearly doubled, and their combined material capacity now exceeds that of the traditional great powers.

Within this context, dollar dominance is slowly eroding.

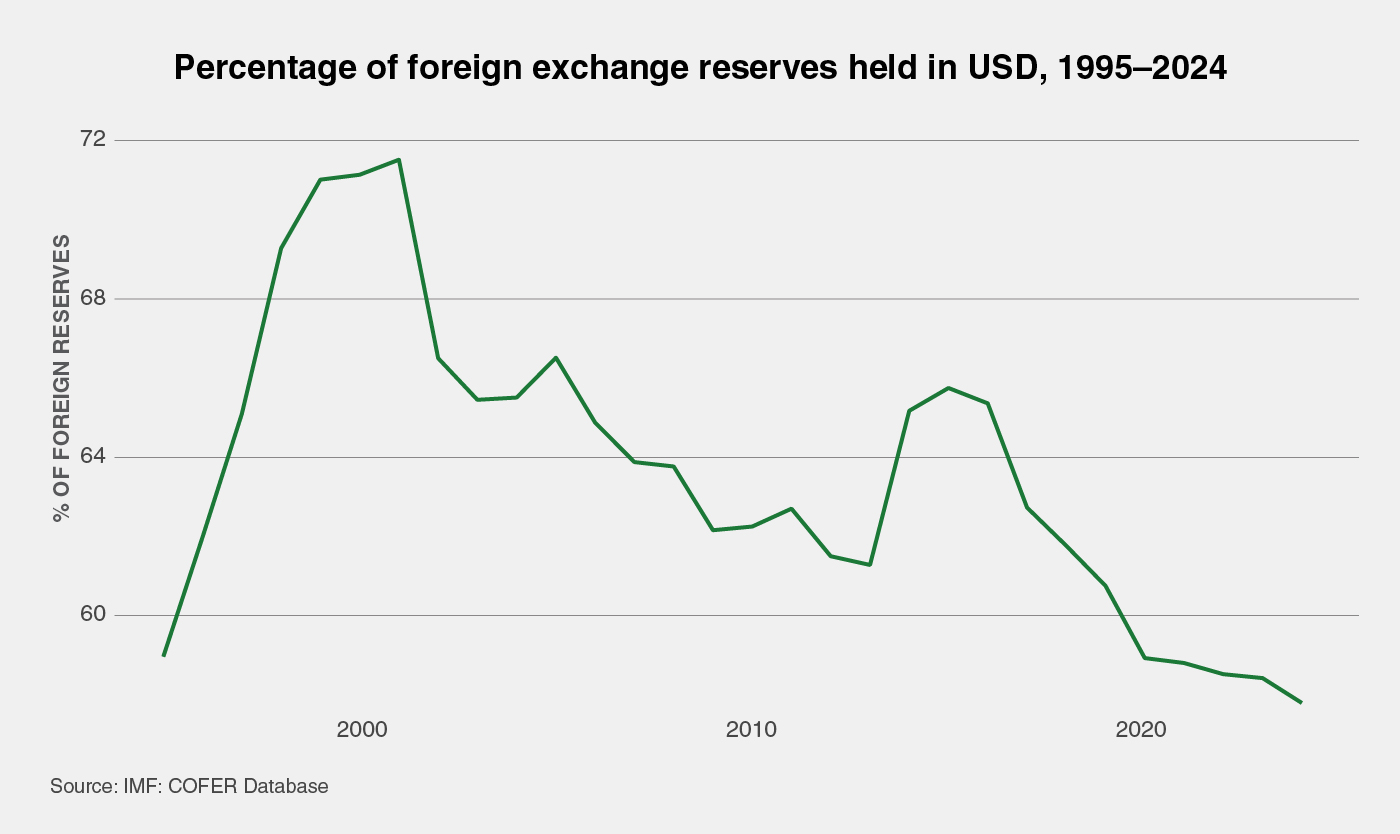

IEP notes that the US dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves has fallen from nearly 72 per cent around the year 2000 to under 60 per cent today, with the BRICS group of major emerging economies – Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and recently expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – cooperating to increase their global economic and political influence, forming a counterbalance to Western-led institutions. And part of this is increasingly settling trade in local currencies.

IMF data show the same direction of travel: the US dollar still accounts for around 55-60 per cent of reported FX reserves, far exceeding the Euro at around 20 per cent and the Chinese yuan at less than three per cent, but the USD share has trended down as “non-traditional” currencies gain ground. This is not collapse, but it is a signal that de-dollarisation is gathering momentum.

The US remains the world’s largest economy, yet its relative economic influence has plateaued. Revised figures show that foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2024 was only $292 billion, lower than the average of the previous decade. These figures reflect a broader slowdown in global investment. The United Nations notes that global FDI fell by 11 per cent in 2024 to $1.5 trillion, with infrastructure investment slowing and trade tensions deterring. The decline in inflows suggests that US economic attractiveness for investors may be falling. However, the US remains the top destination for FDI and accounted for nearly one-fifth of global flows in 2024.

The dollar’s recent decline amid Federal Reserve rate cuts and political uncertainty, highlights additional threats to US currency domination. US trade policy in the past decade has been a further source of instability while China’s dominance around certain commodities means it is in a position of strength around pricing and supply of energy technologies and strategic defence components.

Tariffs introduced during the first US Trump administration and continued restrictions on Chinese technology during subsequent administrations have slowed globalisation and triggered retaliatory measures, with recent conflict over access to rare earth minerals exacerbating this volatility. US tariffs and aid cuts in Southeast Asia contributed to China becoming the default economic partner for six of eleven Southeast Asian nations. In Latin America, protectionist policies and limited investment have similarly allowed China and regional players to increase their economic presence.

For middle powers, this environment presents both a vulnerability and an opportunity. As IEP’s work shows, many of these countries have strong economic profiles but limited military capacity, making them disproportionately exposed to financial coercion and extraterritorial sanctions. A system in which one state controls the main reserve currency, and the plumbing of global payments, amplifies those risks.

In his recent speech at Davos, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney framed the strategic dilemma starkly: “if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu”. His argument, echoing themes from his earlier work on a “multipolar” international monetary and financial system, is that middle powers cannot afford to negotiate individually with a monetary hegemon from a position of dependency.

Carney’s earlier proposals pointed towards a world of multiple reserve currencies, or even a synthetic digital reserve unit backed by a basket of major monies, to reduce the systemic vulnerabilities created by reliance on a single issuer. At Davos he extended this logic into the geopolitical realm, calling on middle powers to act collectively, build institutions that “operate as intended”, and “reduce the leverage that enables coercion”.

For peace oriented institutions this matters because financial leverage is now a routine tool of statecraft. The IEP report documents how sanctions, export controls and trade restrictions have proliferated in the past 15 years, contributing to what it terms “geo-economic fragmentation”. A more diversified reserve currency ecology would not remove this behaviour, but it would make it harder for any single power to impose unilateral economic shocks on broad swathes of the global system.

IEP’s analysis highlights how rising middle powers such as the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia and Türkiye have built influence precisely by diversifying their relationships and avoiding rigid alignment with any one bloc.

These strategies are not ideological de-dollarisation campaigns; they are pragmatic risk management. As academic work on BRICS initiatives notes, reducing dollar dependence is increasingly framed as a question of sovereignty and resilience rather than anti-Western positioning.

From a peace and conflict perspective, the case for middle powers to reduce, rather than abandon, reliance on the dollar rests on three main arguments.

First, diversification lowers the risk of systemic shocks. A global reserve system concentrated in a single currency amplifies the impact of policy errors or domestic turmoil in the issuing state. IEP’s research on fragmentation suggests long term losses to global GDP of up to several percentage points under severe decoupling scenarios. A more multipolar reserve structure, as Carney has argued, would spread risks, expand the supply of “safe assets” and reduce destabilising spill overs from any one country’s monetary cycle.

Second, a less dollar centric system can moderate the escalation ladder in crises. When sanctions on dollar clearing or access to US markets are effectively the “nuclear option” of economic coercion, they can encourage targeted states to respond asymmetrically – through cyber, proxy conflict or escalation in other domains. IEP documents how internationalised intrastate conflicts have nearly tripled since 2010, with rising involvement by external powers. If middle powers have credible alternatives for payments and reserves, there is more room for calibrated, reversible measures rather than all or nothing financial blockades.

Third, diversification strengthens the mediation potential of middle powers themselves. One of IEP’s core findings is that these states are increasingly central to conflict resolution, precisely because they maintain relations with multiple sides and can convene “minilateral” coalitions. If their financial systems are less tightly bound to any single reserve currency issuer, they are better placed to act as honest brokers – hosting reconstruction funds, escrow mechanisms or humanitarian finance that all parties regard as politically acceptable.

None of this implies a sudden, confrontational push against the dollar. The IMF, the Atlantic Council and others all emphasise that, in trade invoicing, cross-border credit and FX trading, the dollar remains deeply entrenched. A disorderly attempt to displace it would itself be a source of instability.

Instead, a peace oriented middle power agenda might rest on five practical steps:

In IEP’s framing, the decisive question of the coming decades is whether rising middle powers use their new influence for “competitive fragmentation or for more inclusive, multi-node cooperation” as dollar dominance erodes and Global South countries gain more financing options in local currencies rather than US dollars.

Further reading: