The past three decades have seen remarkable progress in health and education globally, particularly in low-income countries. Yet income growth has often failed to keep up, leaving countries exposed and fragile, especially given mounting cuts to foreign aid.

The Human Development Index (HDI) measures social progress in three dimensions of human development:

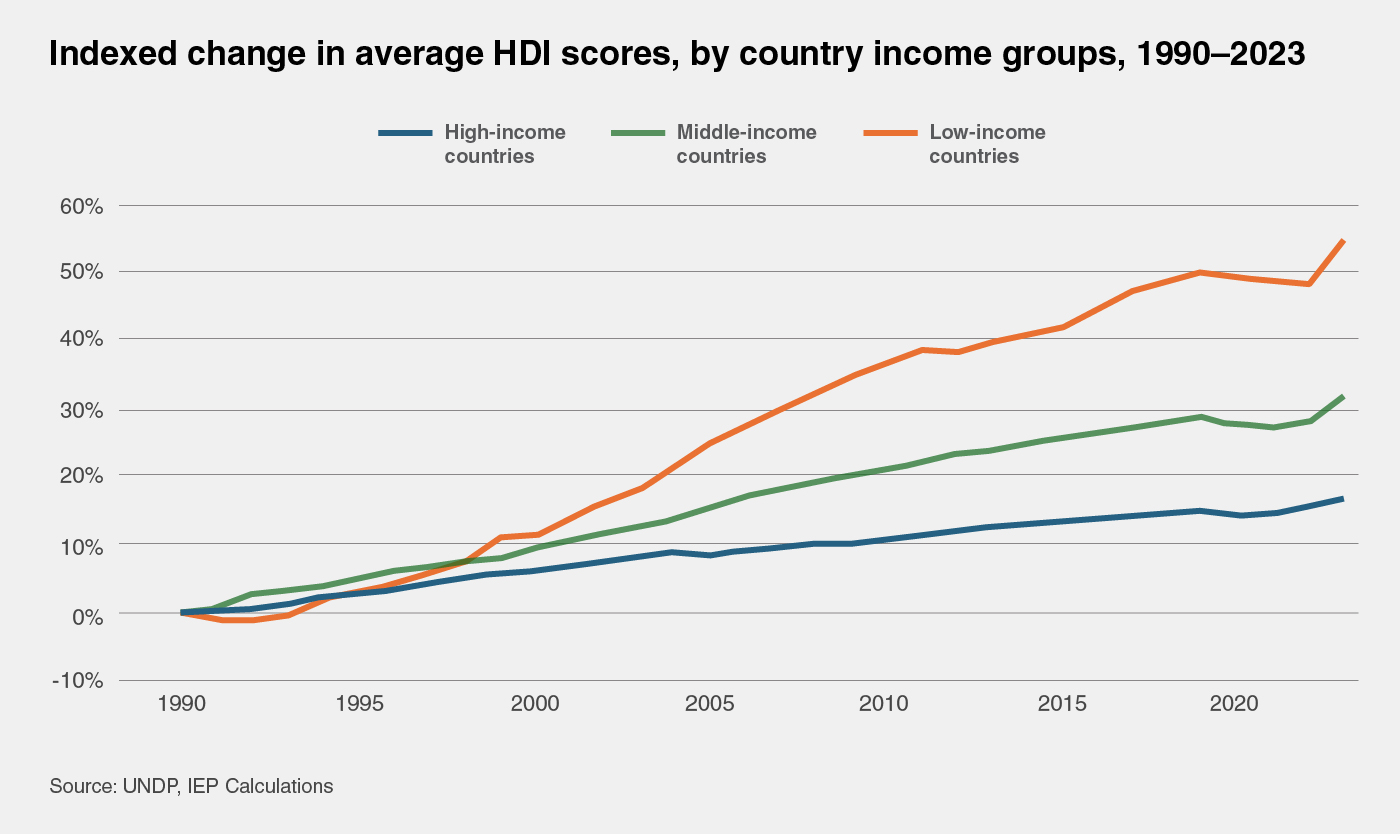

Globally, HDI scores have significantly improved over the past three decades, particularly in low-income countries (LICs). The average HDI score in LICs has risen by about 54 per cent, far outpacing improvements in middle- and high-income countries. This progress has been driven by significant advancements in health and education.

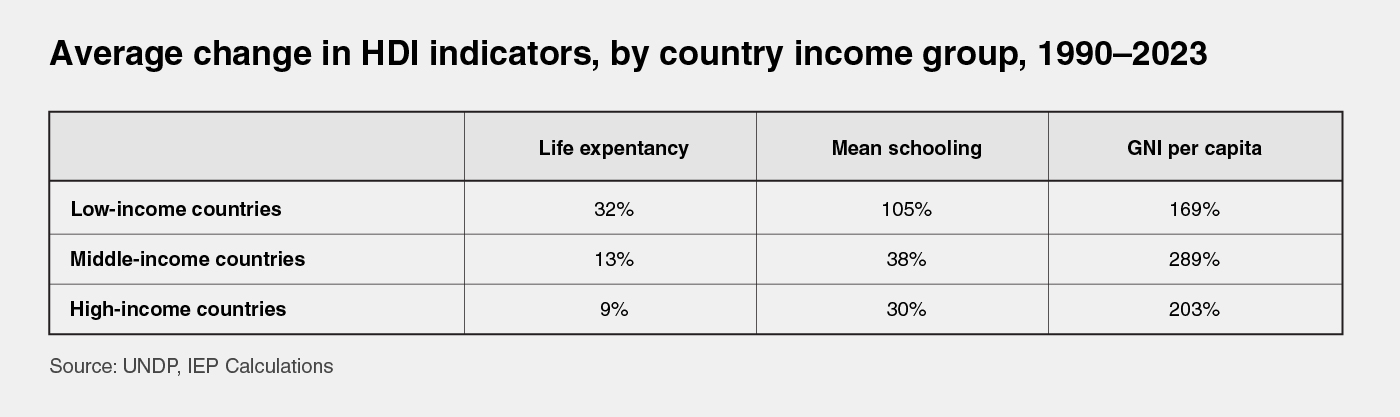

Life expectancy has risen by more than a decade in many LICs, largely explained by medical advancements and access to vaccines, antibiotics and other general health services. Progress against diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and AIDs, backed by international aid, has played an important role. Globally, life expectancy has risen by around nine years, from 64 years in 1990 to around 73 years. In LICs, the improvement has been even greater, with life expectancy rising by around 15 years, from 48 years to 63 years.

Education gains have been perhaps more significant. Mean years of schooling in low-income countries have more than doubled. Initiatives such as the Millennium Development Goals prioritised universal primary education, while the Sustainable Development Goals extended the focus to secondary and tertiary access, gender equality and learning equality. Globally, the average time a child spends in school rose from 7.2 years in 1990 to 9.3 years today.

In contrast to health and education, LICs have experienced the most modest growth in wealth. While the economies of these countries more than doubled in size since 1990, with GNI per capita in LICs rising by 169 per cent, this was the slowest growth of all income groups. GNI per capita in middle-income countries rose by about 289 per cent, while high-income countries rose by 203 per cent, advancing steadily on already large economic bases.

The result? A widening gulf between rich and poor countries. Progress in health and education across LICs remains precarious in the absence of rising incomes to sustain it.

Recent analysis by The Economist finds that the Africa’s economic gap with the rest of the world is growing, even as indicators like life expectancy and schooling improve.

Unlike GNI, which can rise through markets and productivity, gains in health and education for LICs are often more tied to foreign aid. This reliance is what makes these gains fragile. If GNI stalls, and foreign support declines, advances for LICs in the past three decades could be temporary.

Foreign aid, known formally as Official Development Assistance (ODA), has been important to the progress that LICs have made in health and schooling over the past three decades. Unlike foreign direct investment, it is specifically targeted at poverty reduction and providing basic services such as building schools, training teachers and providing health care. Yet this support is now under threat.

OECD research reveals that net ODA is projected to fall by 9-17 per cent in 2025. IEP analysis finds that the long-term reduction could be as high as one hundred billion dollars per year. Among other effects, IEP’s conservative estimates show that this could result in nearly 400,000 additional child deaths over the next few years.

Risks in education are equally serious. Around 68 million children are enrolled in school systems that depend heavily on foreign aid. Declines in funding could lead to results such as overcrowded classrooms, fewer trained teachers and a collapse in the quality of learning. For countries that have built their human development progress on expanding access to education and health, the withdrawal of aid threatens to break decades of efforts.

Human development trajectories reveal both remarkable gains and deepening divides. Over the past three decades, many countries have achieved substantial progress in health and education. Yet widening economic gaps between rich and poor nations leave these gains increasingly vulnerable, especially as foreign aid stagnates or declines. Sustaining progress will depend not only on continued investment but also on addressing the structural inequalities that threaten long-term resilience.