The 2025 Global Peace Index (GPI) reveals a stark reality: 59 state-based conflicts in 2024 led to over 152,000 fatalities, while the economic cost of violence surged to US$19.97 trillion, or 11.6 per cent of global GDP. Compared to 2023, this represents a 3.8 per cent increase, and a 12.5 per cent rise since 2008. These alarming trends are compounded by geopolitical rivalry, weakening multilateralism and a growing gap between peacekeeping mandates and field realities.

Ten years ago, the UN established the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) to assess global state of its peace operations, and its resulting report offered recommendations on how such missions could better “prevent conflict, achieve durable political settlements, protect civilians and sustain peace.” In the time since the report’s release, the world has changed considerably. Nevertheless, many of its contents and recommendations remain critical to the future of peace operations.

In a new report, the International Peace Institute (IPI) takes stock of the current state of UN peacekeeping in light of HIPPO’s findings and proposals. Despite rhetorical commitment to political solutions, many peace operations continue to lack viable political frameworks, and the leverage needed for success. Internal silos within the UN Secretariat hinder flexible deployment, while partnerships especially with the African Union remain underutilised. Although field-level community engagement has expanded, it often fails to influence strategic decisions. In the current fragmented and resource-constrained environment, IPI urges a shift towards modular peacekeeping, tailored to context, and a broader understanding of political engagement beyond formal peace agreements.

The global decline in peacefulness underscores the urgency of the global community supporting peacekeeping efforts to realise their full potential. This is especially important given several countries that have resisted the global trend of rising violence are those where peacekeeping missions have previously succeeded.

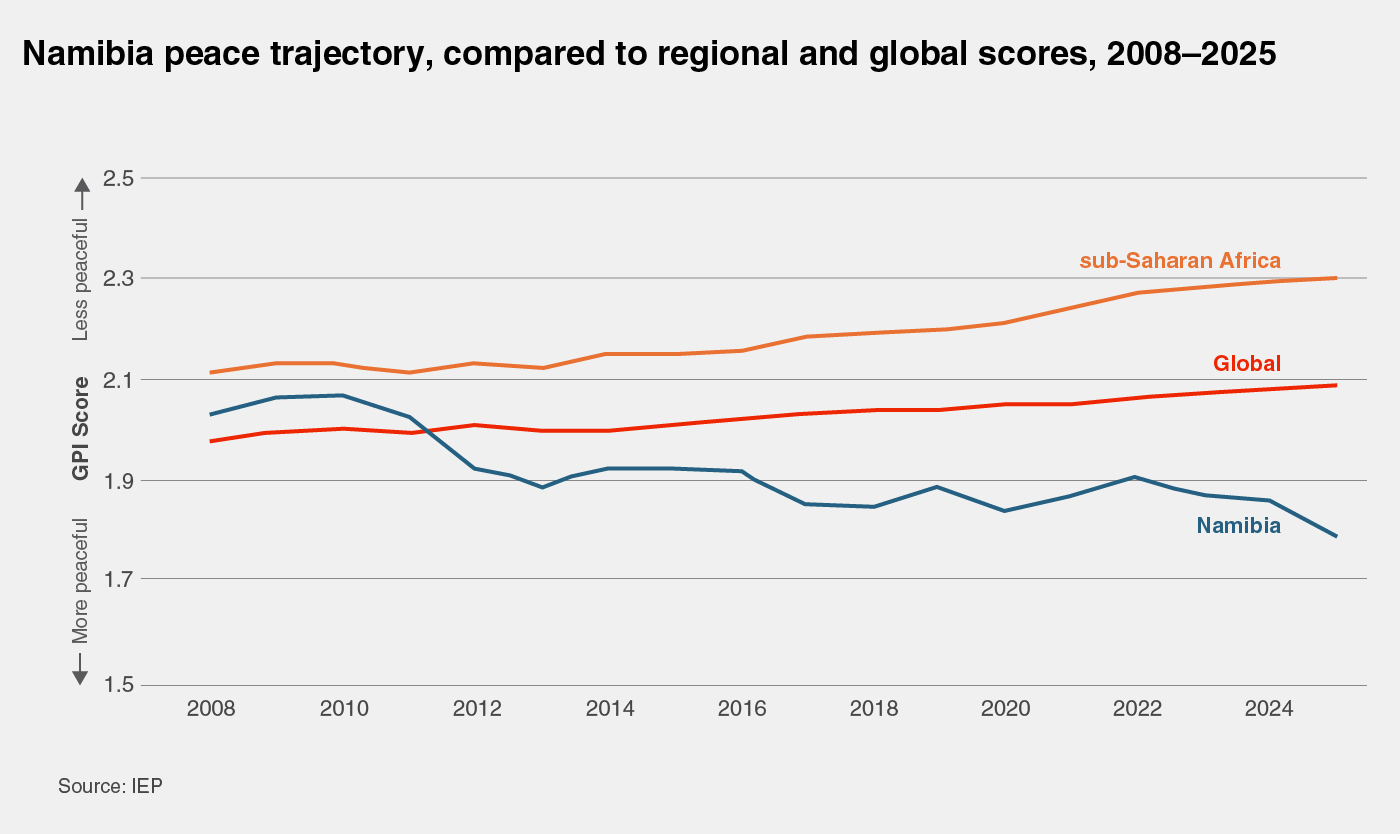

Perhaps no country better illustrates this dynamic than Namibia, which was the site of a successful peacekeeping operation at the time of the country’s independence from South Africa (1989-1990). Built on this foundation, Namibia has become the third most peaceful country in Africa. Over the past two decades, even as the region and the world have become markedly less peaceful, the country has seen its peace score improve by 13.4 per cent, the 11th largest improvement in peacefulness of any country in the index.

Thirty-five years ago, the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) completed one of the most complex and successful missions in UN history and as the first successful case of multidimensional UN peacekeeping. Deployed to support Namibia’s transition from decades of South African occupation to independence, UNTAG remains an example of how peacekeeping – when properly resourced, locally grounded, and politically supported – can change the trajectory of a nation.

Namibia’s path to statehood was shaped by decades of international pressure. After South Africa took control of the former German colony during World War I, the UN revoked South Africa’s mandate in 1966 and declared Namibia under UN jurisdiction. However, South Africa defied international law, imposed apartheid and suppressed local resistance. It was not until the Cold War began to thaw that diplomatic breakthroughs emerged. The UN recognised the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) as the sole legitimate representative of the Namibian people in 1976. And in 1978, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 435, which laid out a peace plan that included a ceasefire and demobilisation, the return of refugees, elections for a constituent assembly and full independence under UN supervision.

Despite armed clashes at the outset of the mission, it persevered with the support of key diplomatic actors, the Secretary-General, and local stakeholders. UNTAG’s approach provides crucial lessons for contemporary peace operations.

Unlike many recent missions, UNTAG enjoyed broad international legitimacy and local consent. The mission was grounded in UN General Assembly Resolution 31/146 (1976), which recognised SWAPO as the sole legitimate representative of the Namibian people, and operationalised through UN Security Council Resolution 435 (1978) – a comprehensive peace plan supported by global powers and regional actors, including South Africa, Angola, and Cuba.

Though its implementation was delayed by Cold War dynamics, the Tripartite Agreement of 1988 paved the way for South Africa’s withdrawal and UNTAG’s deployment in 1989. Crucially, the Namibian people themselves saw the UN as a trusted partner, following decades of international advocacy led by the UN Council for Namibia. That trust was reinforced by consistent engagement and the UN’s visible neutrality. Peacekeepers were welcomed in communities, enabling them to effectively monitor and manage political tensions.

UNTAG’s mandate was clear: enable the conditions for a free and fair election. Every operational element from disarmament to voter registration was aligned with this goal. At its peak, the mission deployed nearly 8,000 personnel, including 2,000 civilians, 1,500 police and 4,500 military staff. This integrated design allowed for flexibility, coordination, and swift response to rising issues. For example, the mission’s electoral and human rights teams worked together to address political intimidation and misinformation during the campaign period. Also, the UN Police monitors also supported the local South West Africa Police (SWAPOL) in transitioning to a neutral, rights-respecting force. The result was a peaceful election with over 97% voter turnout, followed by the drafting of a consensus-based constitution.

The UNTAG mission was supported by sustained diplomatic leadership, especially from the Secretary-General and a “Contact Group” of Western states. When a major crisis erupted on the first day of deployment, with armed SWAPO fighters crossed into northern Namibia from Angola, South African forces interpreted this as a violation of the ceasefire. Violent clashes broke out between SWAPO fighters and the South African Defence Force (SADF), leading to casualties. Rather than abandoning the mission, the UN, with backing from the Secretary-General and Western Contact Group, acted decisively. They negotiated directly with both SWAPO and South Africa, urging a halt to hostilities. A temporary disengagement plan was agreed, and the crisis was contained within a few days, enabling the peace process to remain on track. That strategic patience proved decisive.

Namibia’s story shows that peace is not just desirable, but achievable. It underscores that peacekeeping must be more than a crisis response; it must be a sustained, strategic commitment.

This progress contrasts sharply with the current challenges facing multilateral peace operations. While peacekeepers have reduced violence in many contexts, today’s missions are increasingly constrained. Shrinking budgets, weak political backing, slow deployment and unrealistic mandates have eroded peacekeeping’s effectiveness. Between 2015 and 2024, the number of personnel deployed to multilateral peace operations declined by over 40 per cent, even as 61 missions remained active across 36 countries in 2024.

Peacekeeping is faltering not because it is unworkable, but because it is undervalued. The lessons of Namibia reinforce the effectiveness of deep engagement, strong leadership and a long-term vision. As the UN turns 80, reclaiming peace as a deliberate, collective endeavour is not just an aspiration; it is an imperative.