Over the past 30 years, low-income countries have made striking gains in health and education, but economic growth has generally not kept pace. Nowhere is this discrepancy more acute than in sub-Saharan Africa.

However, while most of the world will see its working-age populations shrink in the coming decades, with uncertain consequences for productivity and social wellbeing, Africa’s growing young population has the potential to usher in a step change in the continent’s economic trajectory. But fully realising this potential will require enhancing the attitudes, institutions, and structures that foster resilience and broad-based prosperity.

Since 1960, life expectancy in Africa has risen by more than half, child mortality has dropped by three-quarters, and university enrolment has increased nine-fold. Yet this social progress sits beside slow economic growth. In 1960, Africans earned about half of the global average; today, it is just a quarter.

The gap between human development gains and economic prosperity is widening, highlighting the fragility of Africa’s progress.

The agriculture sector accounts for 35% of the continent’s GDP, employing more than 50% of its population. This restricts the shift to higher-productivity activities. Productivity growth remains sluggish, with weak infrastructure, limited access to credit and fragmented regional markets all making it difficult for businesses to scale. The World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index consistently places most African countries in the lower ranks.

Corruption is also a persistent obstacle to Africa’s economic development. It undermines the foundations needed to translate human development gains into economic prosperity. The Corruption Perceptions Index developed by Transparency International reveals that sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest scoring region globally, averaging a score of 33 out of 100 in 2024.

Economic costs due to corruption are substantial. The African Union estimates that corruption drains the continent of US$148 billion annually, accounting for about 25% of Africa’s GDP. Such heavy losses further burden already fragile economies while debt mounts.

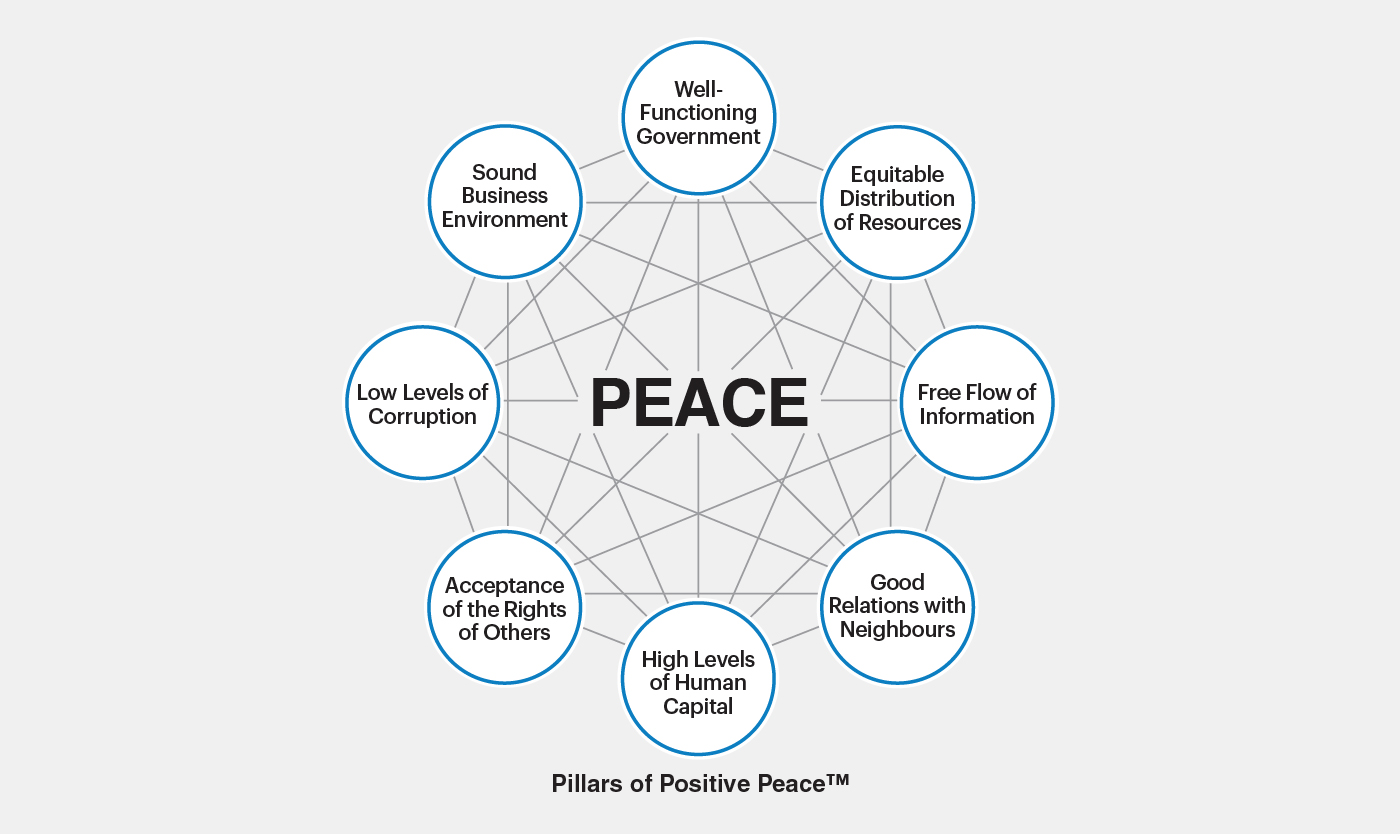

Human development cannot be sustained without the underlying attitudes, institutions, and structures that foster resilient and prosperous societies. This is the foundation of Positive Peace, IEP’s framework built around eight interrelated Pillars that capture the conditions for long-term peace and prosperity.

Viewed through the lens of Positive Peace, Africa’s uneven progress becomes clearer. Advances in health and education coexist with deficits in key Pillars, such as Low Levels of Corruption and a Sound Business Environment. Sub-Saharan Africa performs substantially worse than global averages in both Pillars. Consequences are visible in resource-rich states such as Nigeria and Angola, countries where oil revenues dominate exports and government income. Rather than spending such revenues on development, opaque state-owned companies have diverted funds through mismanagement and corruption, leaving little to support broad-based growth.

The result is the “resource curse”: elites capture resource rents while the wider population experiences stagnation. Dependence on commodities also leaves economies exposed to price swings. When oil prices collapse, fiscal crises follow, cutting investment in critical infrastructure.

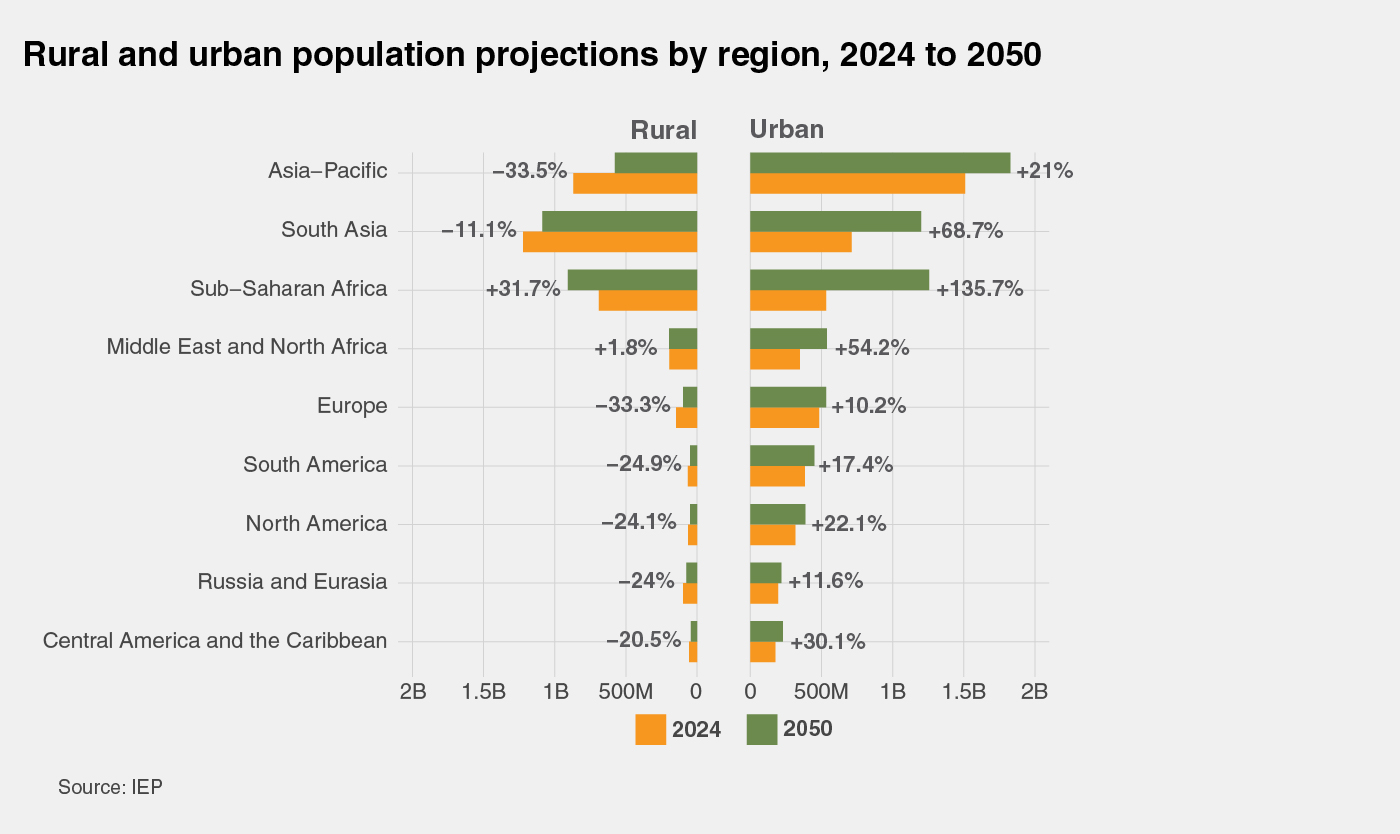

While sub-Saharan Africa’s low GDP per capita growth is partially the result of weak institutions and corruption, it also reflects the sheer scale of its population growth. The continent’s population has doubled to 1.5 billion in just 30 years, so even as the size of the continent’s economic pie has grown larger, this has not translated to economic gains on a per capita basis. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region in the world projected to experience sizeable growth in the coming decades. This growth will take place primarily in urban settings.

This growth represents both a challenge and an opportunity. On one hand, increased competition for jobs, land and resources could heighten inequality and further strain already fragile systems. On the other, it offers the possibility of expanding the economic pie itself. Africa has the world’s youngest population, with over 60% aged under 25. This gives the continent unique economic advantages, because in most of the rest of the world populations are plateauing or shrinking, and ageing workforces are exiting the labour market.

Africa’s large young population will provide a vast labour force and a growing consumer base. Its working-age population will continue to expand well into the second half of the century. If it succeeds in creating enough jobs, this youth bulge could fuel decades of higher growth.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s advances in health and education remain fragile without corresponding progress in income and governance. Corruption is a severe issue that continues to block economic transformation even as population growth and urbanisation reshape the region. The challenge is clear: if rising expectations from a young population can be matched with jobs and opportunity, Africa could become an engine of growth. If not, the continent’s progress in other facets of human development could stagnate or even reverse.