However, there are significant differences in perceptions of safety across different types of government. In this excerpt from the Global Peace Index 2021 report, we investigate global perceptions of safety & risk, by government type.

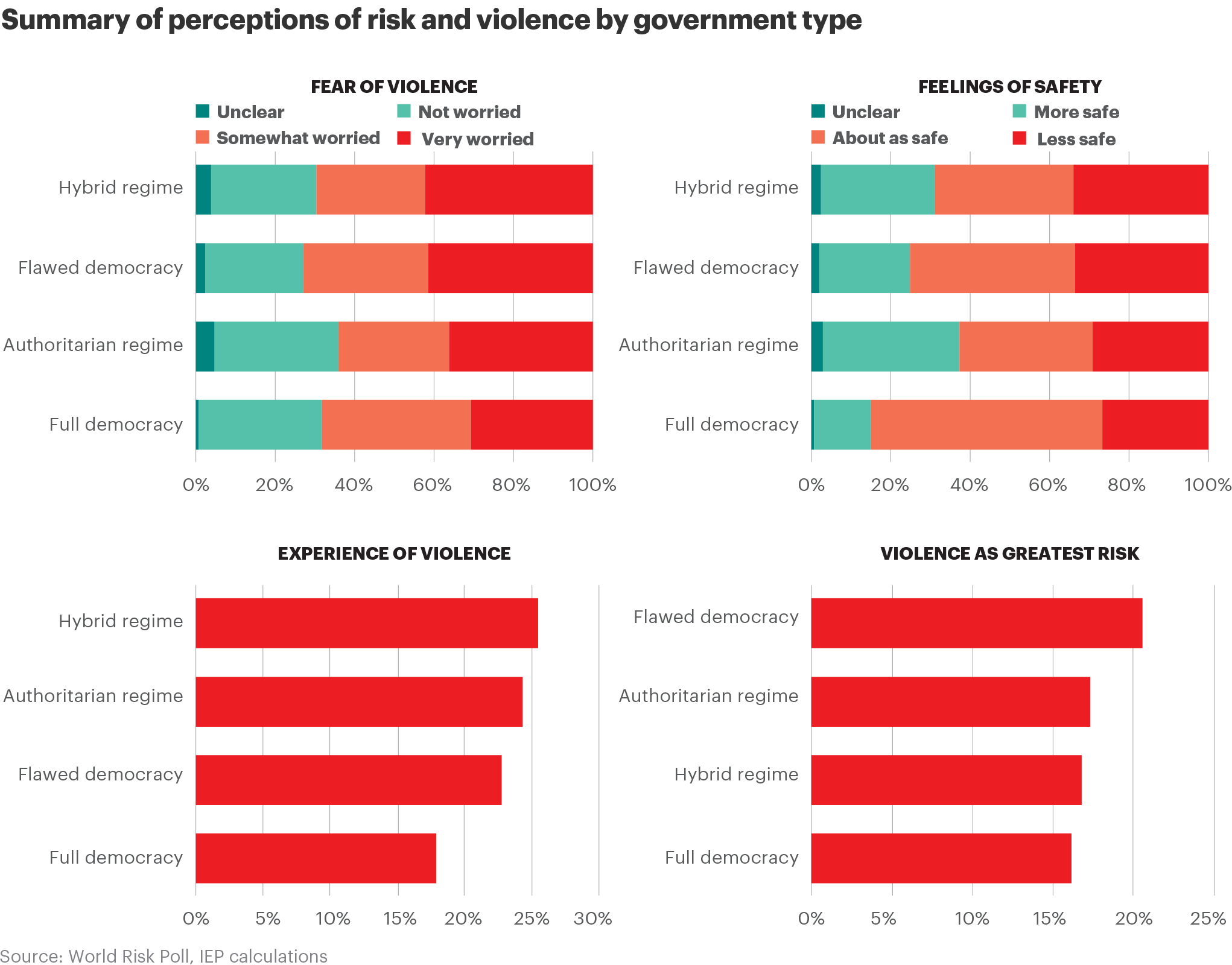

Feelings of safety recorded little change amongst full democracies. They also have the smallest proportion of people of any government type who cite crime, violence, or terrorism as the greatest risk to their safety, with only 14 per cent of the population identifying it as the greatest daily threat. However, it is still the second most cited risk overall amongst fully democratic countries, with only road accidents cited more often. Fear of violence is lower in full democracies than in any other government type, with 31 per cent of people reporting that they are very worried about being a victim of violence. However, Norway is the only full democracy where less than ten per cent of people report being very worried about violence.

Experience of violence is also lower on average in fully democratic countries than any other government type. However, Japan is the only full democracy where the experience of violence rate was lower than ten per cent, with Uruguay, Costa Rica, the United States, and Sweden all having experience of violence rates of 25 per cent or more.

Feelings of safety in flawed democracies has hardly changed compared to five years ago. Thirty-three per cent of people reported that they felt less safe than they did five years ago, compared to 25 per cent who feel more safe. However, the most common response among flawed democracies was feeling as safe as five years ago, at 42 per cent. In 29 of the 47 flawed democracies, over 30 per cent of the population reported feeling less safe in 2019 than they did in 2014. Violence is a bigger concern to people who live in flawed democracies than in any other government type. Over 20 per cent of people in flawed democracies report that the greatest risk to their safety in daily life is violence.

In Brazil, South Africa and Mexico, this percentage is over 50 per cent, with Brazil having the highest percentage of people in the world who report that violence is the greatest risk to their safety. Fear of violence in flawed democracies is higher than in full democracies and authoritarian regimes, with 42 per cent of people stating that they are very worried about being a victim of violent crime. Over 50 per cent of people are very worried about violence in more than a third of the 47 countries classified as flawed democracies, and experience of violence is also high amongst flawed democracies.

Namibia, South Africa and Lesotho have the largest experience of violence rates of any countries in the world. Sixty-three per cent of Namibians have, or know someone personally who has, experienced serious harm from violent crime in the past two years.

People in hybrid regimes had the most varied changes in feelings of safety. Just over 34 per cent of people feel less safe now than they did five years ago, with 33 per cent feeling as safe, and 28 per cent people feeling more safe. Lebanon, a hybrid regime, has the largest percentage of people globally who feel less safe today than they did five years ago, at 81 per cent.

Violence is reported as the greatest risk in hybrid regimes, with 16 per cent of people reporting that it is their greatest threat to safety in daily life. Amongst those countries, Venezuela has the highest percentage of people who view it as the greatest risk, at 45 per cent. Safety and security in Venezuela has decreased significantly since 2014, with its score on the Safety and Security domain on the GPI deteriorating by 32 per cent over this period. Fear of violence is higher in hybrid regimes than any other government type, with 42 per cent of people reporting that they are very worried about violent crime.

However, there is a great deal of variance between hybrid regimes on the fear of violence. Over 75 per cent of people in Malawi report feeling very worried, about violent crime however, Singapore has the lowest percentage of people who are very worried in the world, at less than five percent. More people have had an experience of violence in hybrid regimes than any other government type, at 26 per cent. However, there was considerable variance between countries in this category, ranging from 57 per cent of people in Liberia, to just four per cent of people in Singapore.

Authoritarian regimes have the highest reported rates of increases in feelings of safety, with 35 per cent of people reporting that they felt safer in 2019 than they did in 2014. Rwanda has the largest proportion of people globally who feel safer today than they did five years ago at 67 per cent, closely followed by China at 65 per cent. Only 5.5 per cent of people in China reported that they feel less safe, the lowest proportion of any country in the world. Just over 17 per cent of people in authoritarian regimes see violence as the greatest risk to their daily safety, the second highest of the four government types. Violence was the most commonly cited greatest risk among authoritarian regimes, ahead of road accidents and health concerns.

However, in over a third of countries classified as authoritarian regimes, less than ten per cent of people identified violence as their greatest risk to safety. Only full democracies have a lower fear of violence than authoritarian regimes, with 36 per cent of people being very worried about being a victim of violent crime. Authoritarian regimes also have the highest percentage of people who report being not worried about violence, at 32 per cent. In Uzbekistan, 69 per cent of people state that they are not worried about being the victim of violent crime, which is the highest proportion of any country across all government types.

Despite the increase in feelings of safety and the low fear of violence, the experience of violence remains high in most authoritarian regimes, with 24 per cent of people reporting that they or someone they know had suffered serious harm from violence in the past two years. However, Turkmenistan has the lowest reported experience of violence rate in the world, at one per cent. Afghanistan was the only authoritarian regime with an experience of violence rate higher than 50 per cent.

The four types of regimes are defined as:

Full democracies: Countries in which basic political freedoms and civil liberties are respected by the government, the people and the culture. Elections are free and fair. The government is generally well-functioning and mostly free from bias and corruption due to systems of checks and balances.

Flawed democracies: Countries in which elections are free and fair and basic civil liberties are respected. There may be significant weaknesses in other areas of democracy, such as problems in governance, minimal political participation or infringement on media freedom.

Hybrid regimes: States that hold elections that are not necessarily free and fair. There may be widespread corruption and weak rule of law, with problems regarding government functioning, political culture and political participation. The media and the judiciary are likely to be under government influence.

Authoritarian regimes: Countries in which political pluralism is absent or severely limited, many of which can be characterised as dictatorships. Corruption, infringement of civil liberties, repression and censorship are common. The media and the judiciary are not independent of the ruling regime.