Ecological threats are higher in sub-Saharan Africa than any other region in the world, with the four most at-risk countries Ethiopia, Niger, Somalia and South Sudan, according to Ecological Threat Report 2023.

Of the 221 countries included in the ETR, sub-Saharan Africa, the area and regions of the African continent that lie south of the Sahara, recorded the worst ETR score. 49 of the 52 countries in the region facing at least one severe ecological threat, which include food insecurity, water stress, natural disasters and demographic pressures. Almost 69 million people in the region are exposed to these ecological threats.

By 2050, Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is expected to rise to 2.2 billion, an increase of 60%, which will place further pressure on its already scarce water and food resources. With 35 of 52 Sub-Saharan African countries classified as food insecure, 62% of its population is facing food shortages and 1.4 billion people in this region are projected to be food insecure by 2050.

The ETR reports sub-Saharan Africa is contending with a multitude of challenges that place at risk both its ecological balance and peace. This is due to the direct relationship between ecological threats, seasonal climatic changes and armed conflict. There is a strong correlation between the ecological threats in the ETR and the three Global Peace Index (GPI) domains. All four ecological threats aggravate where countries are less peaceful in the Safety and Security and Ongoing Conflict domains. Militarisation is the only domain in the GPI that is not strongly correlated to ecological threat. Therefore, less peaceful countries have a higher prevalence of ecological threats, particularly food insecurity and water stress.

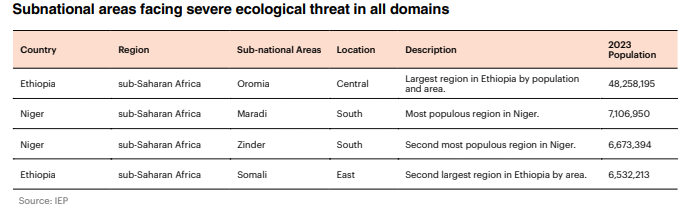

There are four sub-national areas of sub-Saharan Africa that face severe ecological threats in all four domains: Oromia and Somali, the two largest regions in Ethiopia, plus Maradi and Zinder, the two most populous regions in Niger. These are the areas that need the most urgent attention, with both suffering from high levels of conflict and ecological threats. Almost 69 million people living in these areas are exposed to a severe level of water scarcity, food insecurity, demographic pressure, and natural disasters.

Regions with a history of conflict are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and the ongoing conflicts in these areas could potentially intensify as a result of climate change.

For instance, the Sahara transition zone, which covers 7.6% of the total landmass, accounted for almost 16% of all conflict-related deaths in 2020. Nearly 15% of all areas within this transition zone reported at least one fatality, in contrast to only 5% of non-transition zone areas.

In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the issue of food scarcity is a pressing concern. This challenge is further intensified by fluctuating environmental conditions, which are worsened by ongoing conflicts in the region. Food insecurity, along with being a consequence of conflicts, can also contribute to ongoing conflict, acting as both the cause and effect of violence in the region. It is associated with extreme weather conditions, which can exacerbate conflict by pushing the willingness of local populations to fight for control of land and resources.

For instance, Cameroon in Sub-Saharan Africa is plagued with ongoing conflict and ecological threats in sub-national areas that are represented in its food insecurity patterns. Livelihood zones in Cameroon are based on agropastoral farming systems, which includes both the growing of crops and raising of livestock, with the sale of livestock and maize being the major sources of income.

In Cameroon, areas with local maize production in the humid south tend to have lower food insecurity due to two annual growing seasons. In contrast, central and northern regions face high food insecurity, partly due to ongoing conflicts, such as attacks by groups like Boko Haram and Anglophone Ambazonian separatists.

Areas affected by conflict in the north and west are also reliant on cross-border trade, which is disrupted by conflict, leading to inflation and reduced income from cash crops. Meanwhile, Agro-pastoral conflicts occur in regions with one rainfall season leading to droughts which is worsened in regions where terrorist or separatist violence is also prevalent. The existence of other forms of violence, such as terrorism, can exacerbate the disputes between farmers and herders. This violence restricts their ability to reach and utilize land and water resources, compelling pastoralists to intrude upon more remote farming communities.

In sub-Saharan Africa, flooding is associated with increased communal violence in administrative districts where there is a lack of trust in local institutions. Water risk has the greatest impact in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

While most sub-Saharan countries face extreme water stress, some also contend with internal water disparities. For example, in South Africa, eight of the nine provinces suffer from high or severe water risk. In 2018, Cape Town faced the looming possibility of its residents losing access to water with authorities planning to turn off the taps on ‘Day Zero’. Fortunately the crisis was averted by a combination of sustained public communication, engineering solutions and the arrival of rain. In contrast, the Gauteng province and the Johannesburg city have low levels of water risk.

While countries globally experience a shift toward stable or declining population structures, primarily due to the decreasing ratio of young versus older people, sub-Saharan Africa stands out as an exception. Its population is expected to grow by nearly 62% by 2050 to 2.2 billion people. The region’s youth population is increasing at such a rapid rate that by 2050, the number of people aged 15 or younger is projected to surpass the population of Europe.

This rapid population growth means higher demand for resources in already food-insecure and water-stressed sub-Saharan Africa. This can lead to increased competition over common resources and in turn, conflict.

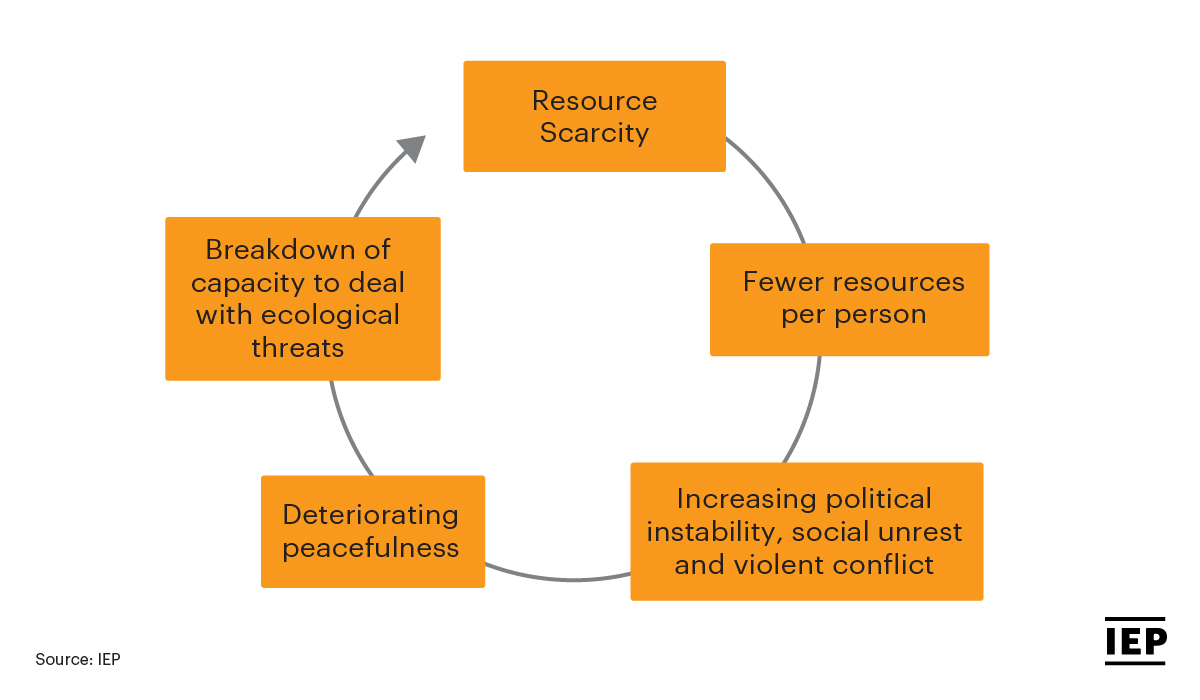

Meanwhile, the dynamics between peace, food insecurity, water scarcity, and population growth are intricate. If multiple ecological threats occur simultaneously, they can merge together, intensify one another and mutually reinforce each other, causing a multiplier effect.

For instance, a country may be exposed to water stress and dedicate resources to addressing this threat. However, the combination of water stress and high population growth may exacerbate food insecurity and even cause higher inflation, unplanned migration or increases in crime. This shows how the relationship between ecological threats and peace can lead to a vicious cycle of resource scarcity. These stressors can lead to increased conflicts that manifest as political instability, social unrest and violent conflict which can cause further state and civilian damage.

Produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace, the Ecological Threat Report assesses threats relating to food insecurity, water risk natural disasters and demographic pressures against societal resilience and levels of peace.