In some countries around the world, foreign aid is crucial to the provision of healthcare. In these places, vulnerable populations, particularly children, tend to face high levels of mortality, making their reliance of health-directed aid particularly acute. Against this backdrop, IEP estimates that anticipated cuts in health-directed foreign aid could result in nearly 400,000 child deaths over the next few years, representing only a fraction of the projected cuts that will have substantial flow-on effects in areas indirectly related to children’s health and wellbeing.

Child mortality is a key measure of health system quality. While there is strong evidence that increased healthcare spending leads to a range of better health outcomes, this indicator, along with measures like child and maternal mortality, tends to be especially responsive to health system investment, largely because it is closely linked to preventable or treatable conditions. This is particularly the case in countries with low baseline investment.

Significant progress has been achieved in recent decades in lowering infant and child mortality, much of it driven by globally coordinated health initiatives, most notably the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (2000-2015). For instance, the global infant mortality rate dropped by 54.6 per cent from 64.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 29.4 in 2017. While child mortality has remained disproportionately high in low-income regions, research has shown that it is in these settings that increases in health spending can have the most substantial positive effects.

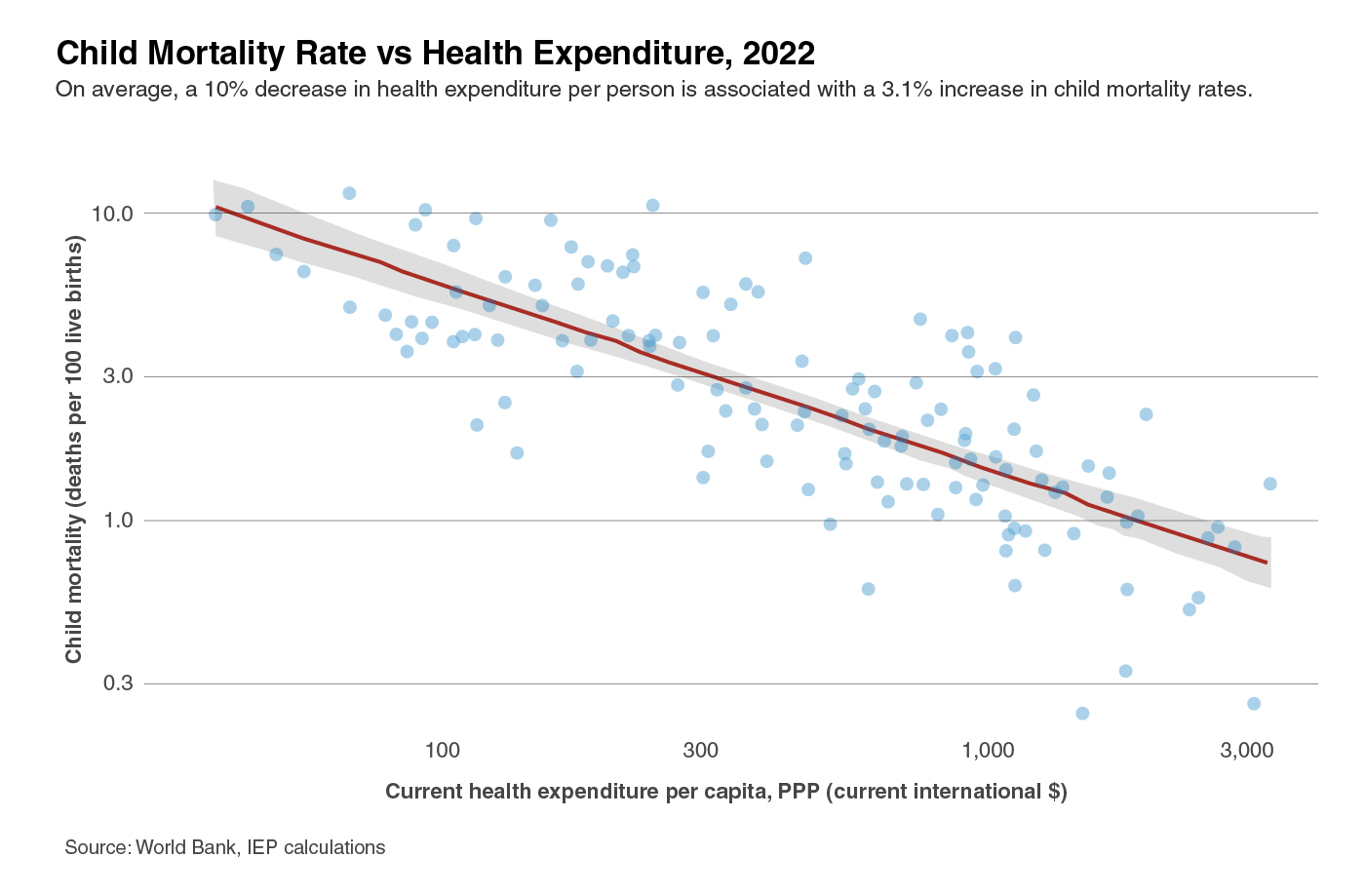

In such contexts, even small increases in healthcare funding can have measurable impacts. For example, it has been found that a one per cent increase in healthcare spending is associated with a decline in infant mortality rates between 0.19 and 1.45 per cent, with the more substantial effects tending to occur in lower income countries. A comparable dynamic is apparent in relation to child mortality, as shown in the following chart, which depicts the relationship between the probability across countries that a child will die before reaching age five, and total healthcare expenditure per capita. Similar to the relationship with infant mortality, this chart suggests that a one per cent increase health expenditure is associated with a 0.31 per cent decrease in child mortality.

Amid the recent turbulence in foreign aid, IEP’s Official Development Assistance report highlights the risks that many countries face to their wellbeing and development due to shifts and potential cuts in funding. It puts forward moderate and pessimistic projections of ODA cuts totalling 20-40 per cent.

In 2023, health-directed ODA totalled about US$16.1 billion, representing about six per cent of total ODA. This does not include an additional US$9.4 billion directed toward specialised policies and programs for population and reproductive health. Health has also not been a priority growth area for ODA over the past decade, with health-directed ODA growing by only 60 per cent in real terms since 2014, compared to 68 per cent growth for ODA overall. In fact, ODA related to population programming and reproductive healthcare is one of the few categories of ODA that saw a decline in funding in the past decade, dropping by 10 per cent since 2014.

Cuts to ODA could have a significant impact on child mortality rates, particularly in countries heavily dependent on foreign aid for their total health expenditure. The lack of access to vaccines, essential treatments and health infrastructure could reverse years of progress in reducing child deaths, disproportionately affecting countries where domestic resources are insufficient to fill the gap left by decreased foreign aid. There are currently 30 countries where more than a quarter of healthcare expenditure comes from aid. The total population of these countries is more than 650 million.

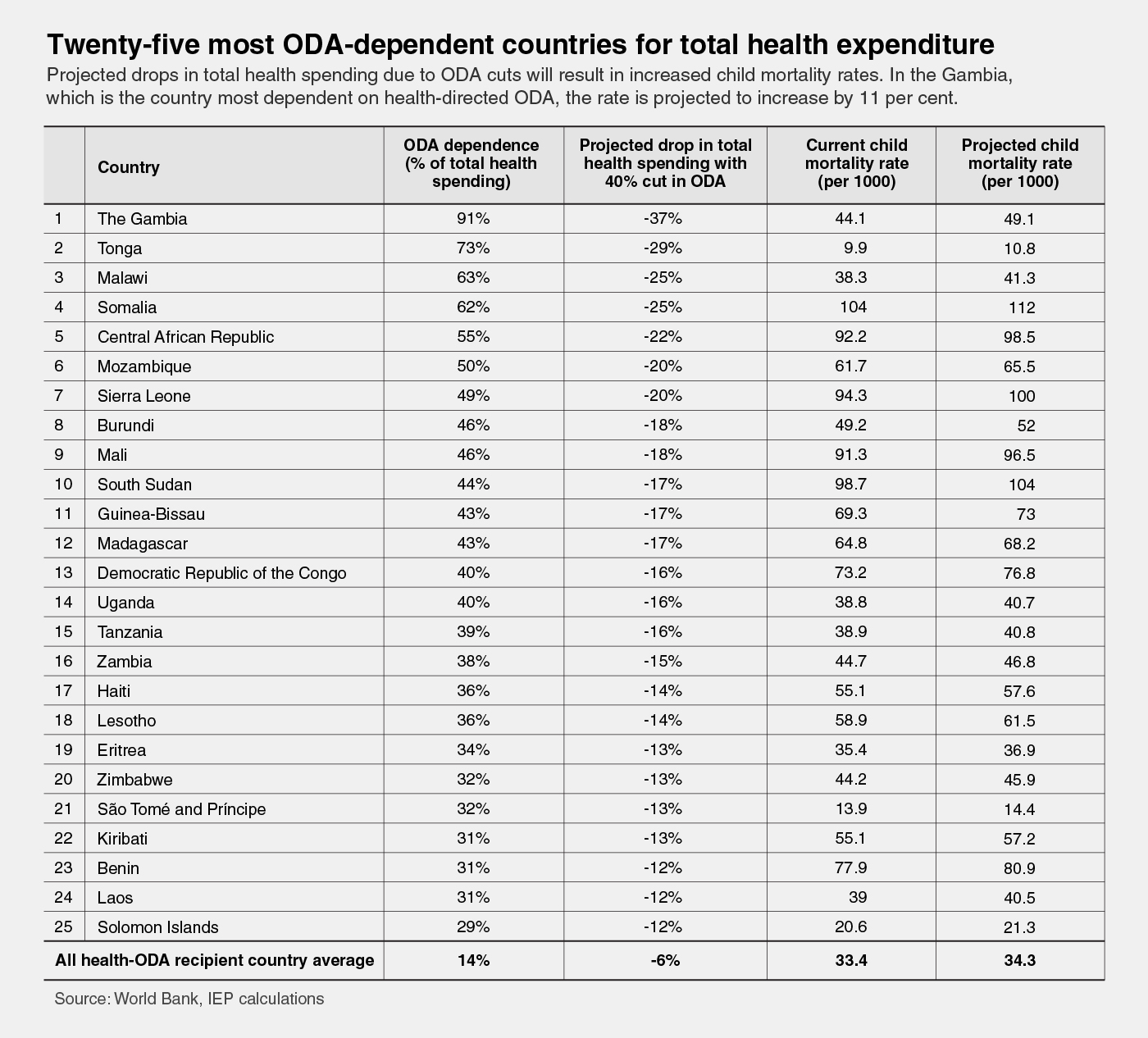

The 25 countries most dependent on ODA for their health spending are shown in the following table. Also shown are their current child mortality rates, how much major cuts in ODA funding would impact their overall health expenditure, and projected increases in their child mortality rates.

In these countries, the impact of ODA cuts would be sizable, with projected increases in child mortality ranging from four to 11 per cent. The Gambia, where around 90 per cent of health spending comes from aid, appears to be the most at risk, though other countries face high levels of threat.

In the vast majority of the over 130 ODA-recipient countries, the threat to child mortality of ODA cuts is substantially less severe. More than half are projected to experience increases of less than one per cent under a pessimistic scenario. However, given that these countries are home to an under-five population of more than half a billion, the potential overall toll of such cuts easily numbers in the hundreds of thousands. IEP estimates that, over next several years, major cuts in health-directed ODA could result in the otherwise preventable deaths of around 380,000 children.

However, this number is likely conservative, as it only measures cuts in ODA directly related to healthcare, though in the coming years ODA is expected to be reduced across a range of categories. In some fragile countries, major reductions in foreign support for sectors like humanitarian relief, security, food assistance, refugee resettlement, education, economic development, and others have the potential to undermine societal health and wellbeing in cascading ways. These could have even more sizable impacts on child mortality than the cuts directly associated with health.