Are you one of the billion active TikTok users? Or are you rather the Twitter type? Either way, chances are you have come across online hate speech.

Hate speech starts offline. It can be accelerated by threats to society. COVID-19 is one such example: the pandemic has fuelled a global wave of social stigma and discrimination against the “other”.

Not surprisingly, anti-Semitism, and more largely racism, is on the rise. A study conducted by the University of Oxford unveiled that around 20% of British adults endorse statements like “Jews have created the virus to collapse the economy for financial gain”. Or “Muslims are spreading the virus as an attack on Western values.”

The internet is where these beliefs can become mainstream. As the new epicenter of our public and private lives, the digital world has facilitated borderless and anonymous interactions thought impossible a generation ago.

Unlike the physical world, however, the internet has also provided a medium for the exponential dissemination and amplification of false information and hate. And tech companies know it.

In 2018, Facebook admitted that its platform was used to inflame ethnic and religious tensions against the Rohingya in Myanmar.

As the lines between online and offline continue to blur, we have a tremendous responsibility: to ensure a safe digital space for all. The opportunity lies in deploying catalytic funding to innovative technologies that combat disinformation, hate and extremism in novel ways.

Even if only 1% of Tweets contained offensive or hateful speech, it would be the equivalent to 5 million messages daily. It is not difficult to imagine the consequences of such virality. The Capitol siege on January 6th painfully exemplifies how social media can incite violence so quickly.

Unlike violent extremism, hate speech is often subtle or hidden in between terabytes of content uploaded to the internet every day. Pseudonyms like “juice” (to refer to Jewish people) or covert symbols (like the ones in this database) feature frequently online.

They are also well-documented by advocacy organisations and academic institutions. The Decoding Antisemitism project, funded by the Alfred Landecker Foundation, leverages an interdisciplinary approach – from linguistics to machine learning – to identify both explicit and implicit online hatred by classifying secret codes and stereotypes.

However, the bottleneck is not how to single out defamatory content, but how to scan platforms accurately and at scale. Instagram offers users the option to filter out offensive comments.

Twitter acquired Fabula AI to improve the health of online conversations. And TikTok and Facebook have gone so far as to set up Safety Advisory Councils or Oversight Boards that can decide what content should be taken down.

With just these efforts alone though, tech companies have failed to spot and moderate false, offensive or hateful content that is highly context, culture and language dependent.

Online hatred is ever-evolving in its shape and form to the extent that it becomes increasingly difficult to uncover. Facebook is only able to detect two-thirds of altered videos (also known as “deepfakes”).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms haven’t been quick enough in cracking down on trolls and bots that spread disinformation.

The question is: did technology fail us, or did people fail at using technology?

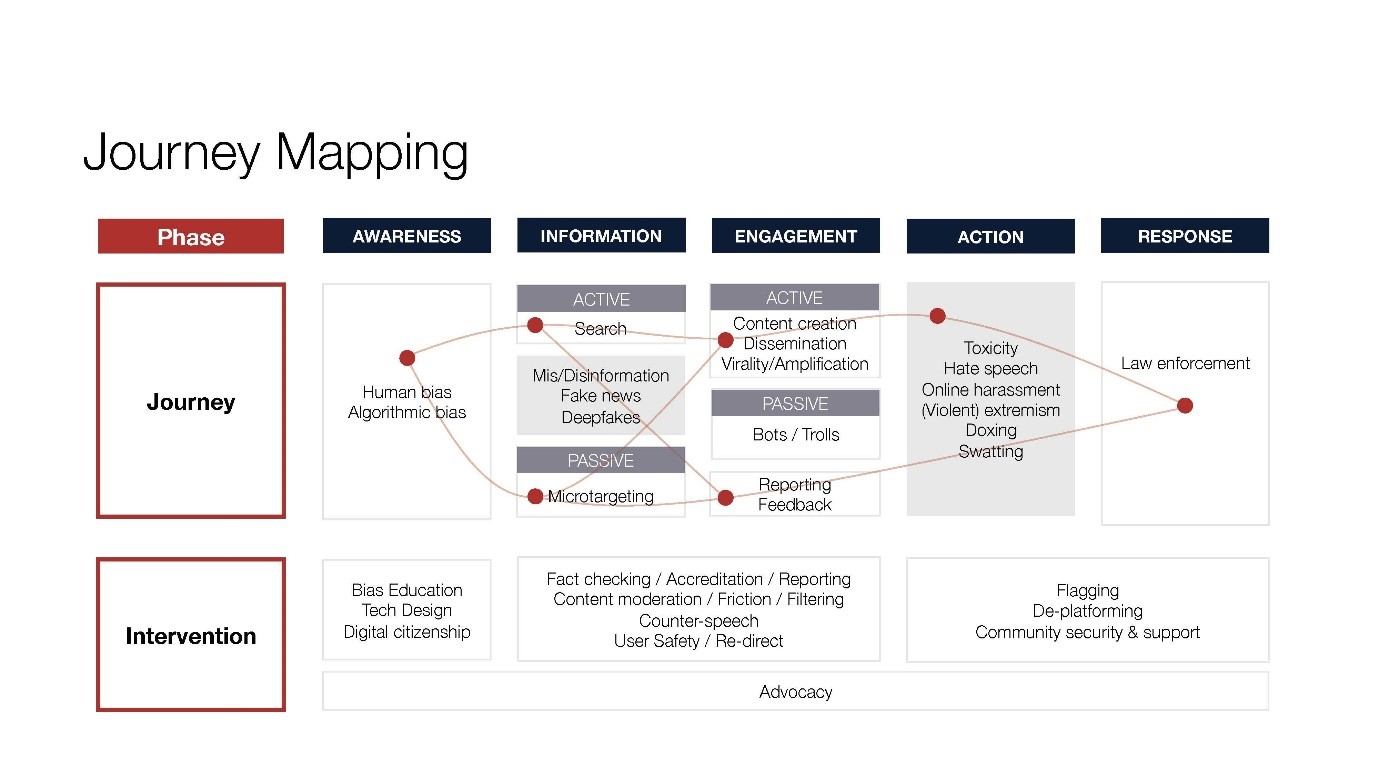

Unless tech companies want to play catch-up on a constant basis, they should move beyond detection and content moderation to a holistic and proactive approach to how people generate and disseminate online hate speech (see chart below).

Such an approach would have the following four target outcomes:

We can design and develop technologies in an inclusive manner by engaging those affected by online hate and discrimination.

For example, the Online Hate Index by the Anti-Defamation League uses a human-centered approach. It involves impacted communities in the classification of online hate speech.

Certain tech designs, like recommendation engines, can accelerate pathways to online radicalisation.

Others promote counter-speech or limit the virality of disinformation. We need more of the latter. The re-direct method employed by social enterprise Moonshot CVE channels internet users who search for violent content towards alternative narratives.

Tech platforms have primarily focused on semi-automated content moderation, through a combination of user reporting and AI flagging.

However, new approaches have emerged. Samurai Labs’ reasoning machine can engage in conversations and stop them from evolving into online hate and cyberbullying.

By ensuring that we hear every voice and that we empower citizens to engage in civic discourse, we can help build more resilient societies that don’t revert back to harmful scapegoating.

In the US, New / Mode makes it easier for citizens to affect policy change by leveraging digital advocacy tools.

There is a common denominator in the four ways we can combat online hate speech. And that is, with the help of technology, they address the root of the problem.

Indeed, it is no longer tech for the sake of tech. From Snapchat’s Evan Spiegel to SAP’s Christian Klein, dozens of CEOs signed President Macron’s Tech for Good call a few months ago.

Beyond pledges, companies are embracing technology’s potential to be a force for good. For example, by setting up mission-driven incubators, like Google’s Jigsaw, or by allocating funds to incentivise fundamental research, like WhatsApp’s Award for Social Science and Misinformation.

In conversations with various research organisations, such as the Institute of Strategic Dialogue (ISD), I have learnt firsthand about the demand for tech tools in the online hate and extremism space.

Whether it is measuring hate real-time across social media or identifying (with high levels of confidence) troll accounts or deepfakes, there is room for innovation.

But the truth is that the pace and the various ways in which people use tech to incite and promote online hatred is faster and more intricate than what companies can preempt or police.

If the big platforms can’t solve the conundrum, we need smaller tech companies that will. And that is why catalytic funding for risky innovation is key.

With the increase of hatred due to COVID and the higher demand for new solutions, it is only natural that funders and investors become interested in scaling for-profit and non-profit early-stage tech tools.

Established venture capital players like Seedcamp (investor in Factmata) and companies like Google’s Jigsaw are starting to bridge the gap between supply and demand to combat disinformation, hate and extremism online.

But we need more. And so I invite you to join me.

This article was originally published on World Economic Forum under Creative Commons Licence.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Vision of Humanity.