The accord, brokered in Washington by US President Trump, follows years of intermittent war, fragile ceasefires and shifting geopolitical alignments. The leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nikol Pashinyan and Ilham Aliyev, signed the agreement after 40 years of conflict, centred around the disputed region of Karabakh.

It has drawn positive reactions from Türkiye and European actors, while neighbouring countries, including Russia and Georgia, have reacted positively to the new US-brokered peace deal which ended decades of conflict. Some analysts report that the deal is a significant shift in regional power dynamics, diminishing Russia’s influence, while bolstering US presence, and Iran said it will block a planned corridor in the Caucasus, citing concerns over the potential negative consequences of any foreign intervention near its borders.

The agreement has the potential to reshape the South Caucasus, an energy-producing region bordering Russia, Europe, Türkiye, and Iran. The area is intersected by key oil and gas pipelines but constrained by closed borders, such as between Türkiye and Armenia, and by longstanding ethnic tensions.

Iran described the accord as “an important step toward lasting regional peace,” while cautioning that foreign intervention near its borders could “undermine the region’s security and long-term stability.”

The European Union said that once implemented, the peace agreement would have a positive impact on the overall peaceful development of the region.

The first Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan was the most violent conflict resulting from the break-up of the USSR. Armenia’s historical experience of genocide, ethnic polarisation, communal violence, armed conflict, and military capacity contributed to a perceived existential threat that made Nagorno-Karabakh a territory at high risk of genocide, with the risk existing on both Azerbaijani and Armenian sides.

The late 1980s saw the region’s secession from Azerbaijan, backed by Armenia, sparking war and displacement. In 2020, renewed fighting ended with Azerbaijan regaining significant territory. By 2023, Baku had reasserted full control of Nagorno-Karabakh, triggering the exodus of almost all of its ethnic Armenian population.

The agreement commits both sides to cease hostilities permanently, open full diplomatic relations, and respect each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. It also provides for the dissolution of the OSCE Minsk Group, established in 1992 to mediate the dispute, acknowledging its limited success in delivering a lasting settlement.

The centrepiece of the deal is the creation of a 43-kilometre transit corridor through southern Armenia, dubbed the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). This link will connect mainland Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan exclave and, via Türkiye, to European and Mediterranean markets. The US has secured exclusive development rights over the corridor for 99 years, with plans for rail, road, oil and gas pipelines, fibre-optic lines, and potential electricity transmission infrastructure.

From an economic perspective, TRIPP is forecast to unlock up to $45 billion in infrastructure and energy opportunities, diversifying Azerbaijan’s export routes and offering Armenia new channels for trade and investment after years of economic isolation.

The peace deal could signal a strategic shift of the region’s balance of power. Apart from Iran’s concerns, the deal also side-lines Russia, whose influence in Armenia has eroded amid its focus on the war in Ukraine and Yerevan’s gradual orientation towards the West.

For Armenia, integration into projects like the Middle Corridor, a trade route between Europe and China bypassing Russia and Iran, becomes more viable, promising economic benefits that may reduce the incentives for renewed conflict. For Azerbaijan, the removal of US defence cooperation restrictions opens opportunities for security sector modernisation and deeper bilateral ties with Washington (SBS, 2025).

The geopolitical re-alignments implied by the corridor are significant. A sustained US commercial and strategic presence in the South Caucasus could reshape transit and energy flows in ways that diminish the leverage of Moscow and Tehran, while embedding both Armenia and Azerbaijan more firmly in Western economic and political networks.

The peace deal’s durability will depend not only on infrastructure delivery but also on political follow-through. Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev has called for Armenia to amend its constitution to remove what he describes as “baseless territorial claims”, a process expected to require a referendum in 2027. This demand risks inflaming domestic opposition within Armenia and could become a point of renewed tension.

Civil society voices, such as Freedom Now, have also urged the US to press Azerbaijan on human rights, including the release of political prisoners. Addressing these governance concerns may be important for sustaining public support for the agreement, both domestically and internationally.

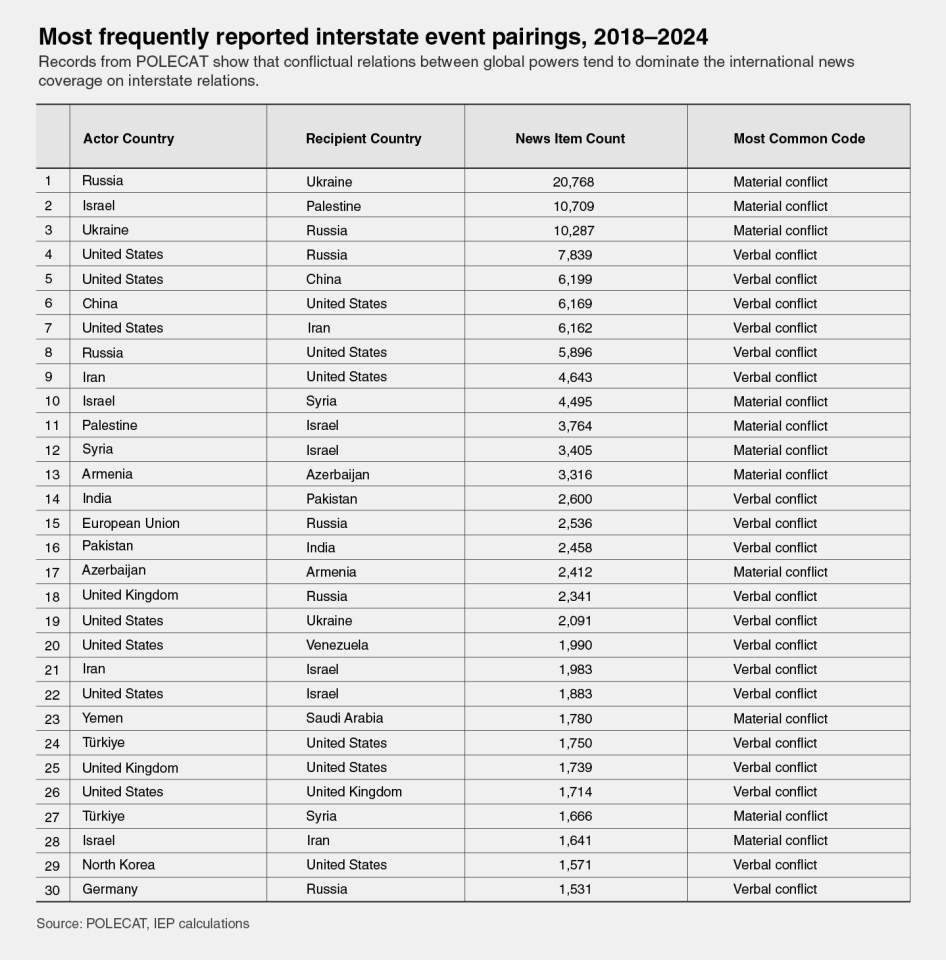

The conflict has been one of the world’s top 20 most mentioned in the media over the past seven years, according to the Global Peace Index 2025.

The peace agreement represents the most substantive attempt at a comprehensive settlement since the conflict began. The agreement’s blend of political commitments, economic incentives, and strategic re-alignment aligns with long-standing GPI findings: that sustained improvements in peacefulness are most likely when reductions in ongoing conflict are matched by gains in economic opportunity and institutional capacity.

However, history cautions against assuming that a signed treaty equals lasting peace. Border incidents, constitutional disputes, and unresolved grievances could re-emerge as triggers for renewed hostility. Regional rivalries, particularly with Iran and Russia, add an additional layer of complexity.