Positive Peace as a term was first introduced in the 1960s by Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung and has historically been understood qualitatively based on idealistic or moral concepts of a peaceful society.

The distinguishing feature of IEP’s work on Positive Peace is that it is empirically derived and therefore conceptually different from Galtung’s version. Statistical analysis and mathematical modelling was used to identify the common characteristics of the world’s most peaceful countries. It therefore forms an important evidence base to understand Positive Peace and avoids subjective value judgements.

Human beings encounter conflict regularly — whether at home, at work, among friends or on a more systemic level between ethnic, religious or political groups. But the majority of these conflicts do not result in violence. Conflict provides the opportunity to negotiate or renegotiate to improve mutual outcomes. Conflict, provided it is nonviolent, can be a constructive process. There are aspects of society that enable this, such as attitudes that discourage violence or legal structures designed to reconcile grievances.

This is acknowledged and understood in IEP’s Positive Peace research.

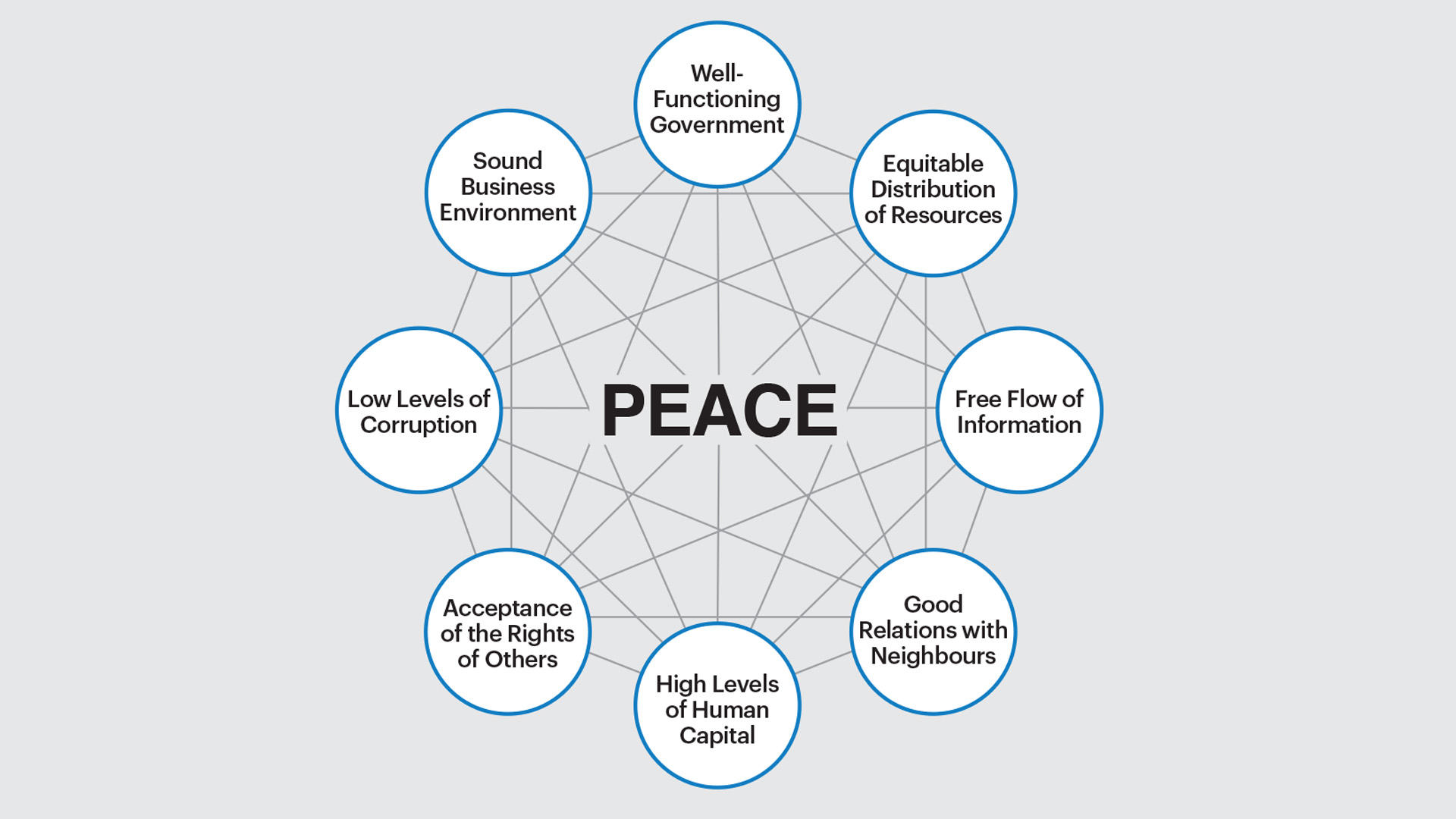

To construct the Positive Peace Index (at the heart of the PPR) nearly 25,000 national data series, indexes and attitudinal surveys were statistically compared to the internal measures of the Global Peace Index to determine which factors had the highest statistical correlations.

Indicators were then qualitatively assessed and where multiple variables measured similar phenomena, the least significant or indicators with the poorer data were dropped. The remaining factors were clustered using statistical techniques into the eight Pillars of Positive Peace. Three indicators were selected for each Pillar that represent distinct but complementary conceptual aspects.

The index was constructed with the weights for the indicators being assigned according to the strength of the correlation coefficient to the GPI Internal Peace score. This empirical approach to the construction of the index means it is free from pre-established biases or value judgements. It is also highly robust. Various tests have been performed, including using alternative methods of weighting which have produced similar results.

Systems theory first originated while attempting to better understand the workings of biological systems and organisms, such as cells or the human body. Through such studies, it became clear that understanding the individual parts of a system was inadequate to describe a system as a whole, as systems are much more than the sum of their parts.

Think of human beings, our consciousness is more than sum of our parts. Extending these principles to societal systems is a paradigm shift, allowing for a more complete understanding how societies work, how to better manage the challenges they face and how to improve overall wellbeing. This approach offers alternatives to traditional understanding of change.

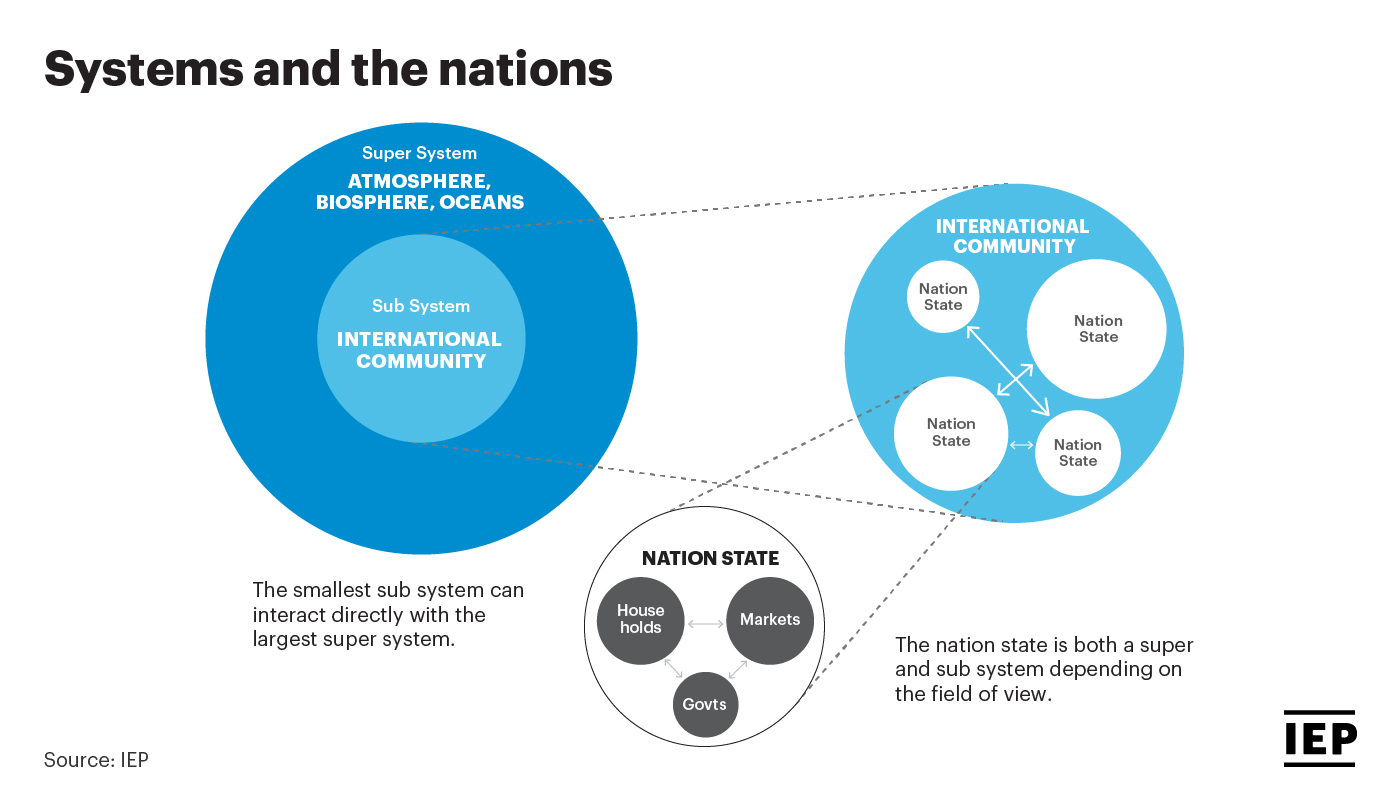

All systems are considered open, interacting with the sub-systems within them, other similar systems and the super-system within which they are contained. A societal system is made up of many actors, units and organisations spanning the family, local communities and public and private sectors. As all of these operate individually and interact with other institutions and organisations, each can be thought of as their own open system within the societal system.

Sub-systems may, for instance, include companies, families, civil society organisations, or public institutions, such as the criminal justice system, education or health. All have differing intents and encoded norms. Similarly, nation states interact with other nations through trading relations, regional body membership and diplomatic exchanges, such as peace treaties or declarations of war.

The nation state itself is made up of these many sub-systems, including the individual, civil society and business community. Scaling up, the nation can be seen as a sub-system of the international community, in which it builds and maintains relationships with other nations and international organisations.

Finally, the international community forms a sub-system of a number of natural systems, such as the atmosphere and biosphere.

From a systems perspective, each ‘causal’ factor in any system does not need to be understood. Rather, multiple interactions that stimulate the system in a particular way negate the need to understand all the causes.

Processes can also be mutually causal. For example, as corruption increases, regulations are created, which in turn changes the way corruption is undertaken. Similarly, improved health services provide for a more productive workforce, which in turn provides the government with revenue and more money to invest in health. As conflict increases, the mechanisms to address grievances are gradually depleted increasing the likelihood of further violence.

Systems are also susceptible to tipping points in which a small action can change the structure of the whole system. The Arab Spring began when a Tunisian street vendor who set himself alight because he couldn’t earn enough money to support himself.

The relationship between corruption and peace follows a similar pattern. IEP’s research has found that increases in corruption have little effect until a certain point, after which even small increases in corruption can result in large deteriorations in peace. Similar tipping points can be seen between peace and per capita income, inflation and inequality.

Download the Positive Peace Report 2022 here.