South Sudanese lawyer Ajak Mayol Bior can be easily located these days. He spends most of his time at his apartment or his chambers, or at the courts of Juba, the capital of South Sudan, whether that’s the High Court, the Court of Appeals or, on rare and dignified occasion, the Supreme Court.

As child however, Bior was much harder to locate. He was taken from his remote village in the early nineties and became an itinerant child soldier; one of the famed Lost Boys of Sudan. Ajak Bior was born sometime late in the seventies or early eighties (he, like most South Sudanese men born in that era, has no birth certificate) in a remote village in Bor State near the White Nile River. Born into a Dinka family, Bior’s family lived traditionally, with the river, river delta and pastoral land of the famed Dinka cows being sacred ground; the wellsprings from which all Dinka life flowed.

Access to the river and pastoral land was highly regulated by traditional law, expressing the ideal relationship with the people, the river and the cows. Although not codified, traditional Dinka law was highly complex and systemic, with marriage protocols, land and property disputes, food and water distribution, and other important parts of Dinka life strictly regulated. These traditional laws remain in common use in South Sudan today, and even now when Bior is in court in Juba he sometimes uses a mix of statutory, common and traditional law, which is accommodated by the South Sudanese courts.

In Ajak Mayol Bior’s childhood however, all law was eventually usurped by a brutal war partially fought about law. On one side was the northern federal army of Sudan, commanded mostly by Muslims and hoped to bring sharia to the south. On the other was the militias of the south, who were mostly Dinka and Nuer tribesmen who wanted to keep their traditional system of law.

In the nineties the war was total, pushing communities from their rivers, pastoral lands and traditional homes, killing hundreds of thousands of people and sending children into combat.

Ajak Mayol Bior estimates he was perhaps ten or eleven years of age when he was conscripted. Bior fought as part of the Jesh al Ahmr or Red Army, a liberationist force of predominantly child soldiers fighting alongside the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army or SPLA, now the most significant and influential element in the South Sudanese government.

It is estimated that at its peak the Red Army numbered tens of thousands of boys, and that thousands of these conscripts died during the war. Bior says that many of these deaths were due to malnutrition or starvation, and that hunger was a significant driver for the conscripts, who were detached from traditional food chains and often left to try to find their own sustenance.

‘That was a major part of our existence,’ says Bior. ‘We’d be in the bush and we would be starving and sometimes we had to go to an enemy town and attack to survive. We had to fend for ourselves and it was very hard. We had to protect ourselves and band together and work together,’ he says. ‘We must divide everything equally or we would all die.’

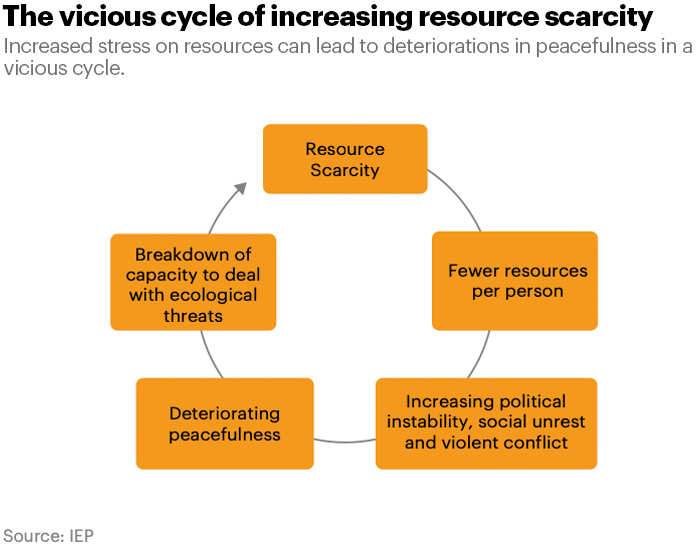

One of the key findings from the Ecological Threat Report 2021 was that a scarcity of resources combined with food insecurity can form a vicious cycle in which the depletion of resources and violent disputes reinforce one another.

Bior stresses that the Red Army had a no tolerance policy for food looting, and that boys in his battalion would be shot for getting caught stealing food in towns they had liberated. He also says that even the willing accommodation of soldiers in a town where food insecurity was already high would put further stresses on food availability and fuel competition for resources. Furthermore, in the case of South Sudan, the destruction or seizure of pastoral land, the massacre of cows and the pollution of the Nile increased levels or hunger and food insecurity, had the effect of further inflaming the conflict, resulting in further resource degradation.

This perhaps was less significant in inspiring conflict between the north and south, but it is undoubtedly a driver of the intertribal conflict that flared up many times during the war and became its own civil war after South Sudan became independent in 2011. Another factor that may be driving conflict in areas where food is scarce is the impaired decision making and anger that can be borne of calorific deficient, though this relationship is not yet well researched. ‘Of course, it was not good being hungry. It did not feel good,’ Bior says of his experiences.

After time in Palotaka and Torit in the nineties, two places where many of the Red Army conscripts attempted to build communities, Bior eventually made his way to the vast refugee camp of Kakuma. Kakuma was located just across the Sudanese border in Kenya, where many of the survivors of the war spent time. Bior then studied in Kenya and finished his secondary education in Nairobi. After a peace agreement was in progress and South Sudan was on a path to independence, he returned to Sudan.

Photo © Derek Hudson/Getty Images

In Sudan, he was remobilised into the army, working in administration and IT, before demobilising and enrolling at the University of Juba’s law program. These studies took Bior to Khartoum, the capital of his former enemies, to compete his studies. Now he has been practising law in Juba for ten years.

Bior’s life is far easier than it had been during the war of the nineties, but his is not a story of happily ever after. Violence is still rife in South Sudan and, plagued by several internal conflicts, is ranked 160th in the Institute of Economics and Peace’s Global Peace Index. Only three countries fare worse: Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan. The Ecological Threat Report 2021 has found that food risk in South Sudan is currently at the highest level gauged. Furthermore, South Sudan is one of the ETR’s thirty hotspot countries where high ecological risk and low level of societal resilience is likely to create further conflict.

Against this background, Ajak Mayol Bior continues to fight, but no longer with an AK-47. Questions of justice are of paramount importance in South Sudan, a place where, according to the Positive Peace Index 2020, corruption levels are second only to Yemen and Somalia. The South Sudanese courts are imperfect, with widespread vested interests and judicial independence still absent. Yet in the face of all this, every day Ajak Mayol Bior moves between his apartment and his chambers and the courts, committed to his work and hoping to move slowly towards an equitable and peaceful South Sudan.

Produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), the Ecological Threat Report covers over 2,500 sub- national administrative units or 99.9 per cent of the world's population. It assesses threats relating to food risk, water risk, rapid population growth, temperature anomalies and natural disasters.

Read the report