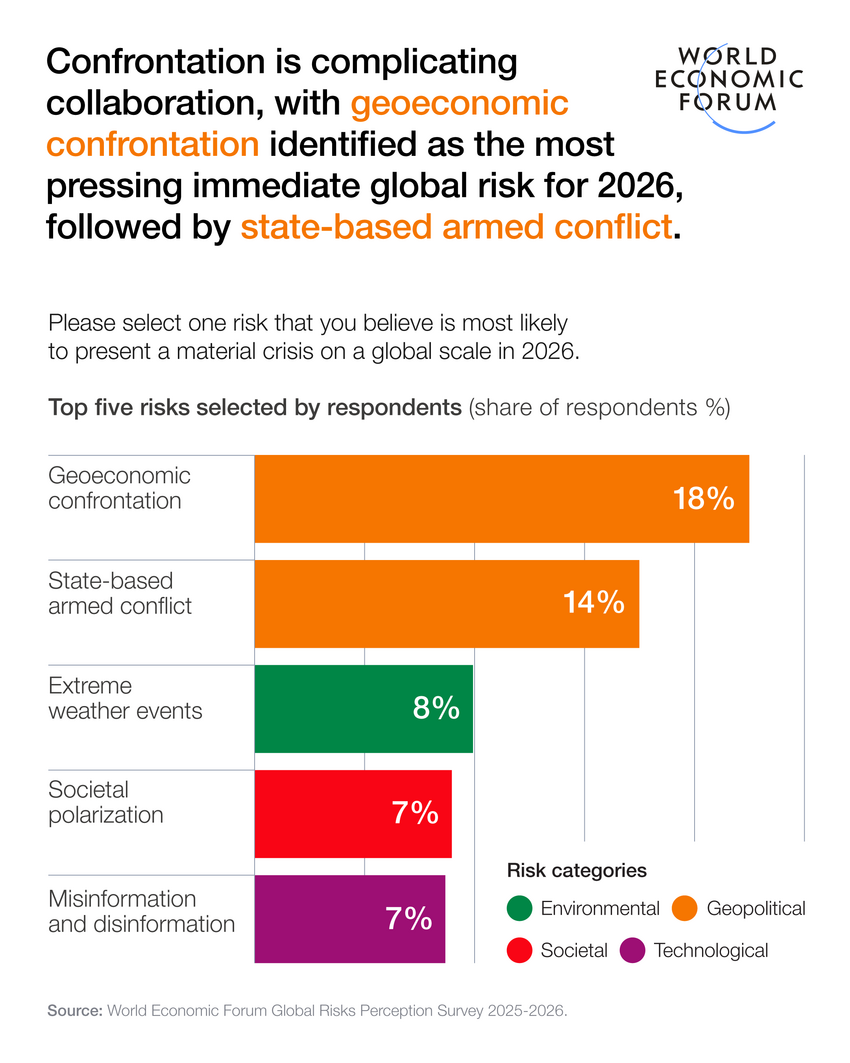

“Geoeconomic confrontation” – a term that refers to the weaponisation of economic tools like tariffs, investment controls and sanctions – is now considered the leading threat to world peacefulness, edging out traditional warfare and extreme weather events.

The fresh warning has emerged from the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Risks Perception Survey 2026, which polled over 1,300 experts.

This shift reflects how economic stress, from protectionist trade policies to resource competition, can strain international relations and domestic cohesion. Economic downturns often coincide with social unrest, eroding trust in institutions, fuelling nationalism and squeezing ordinary people’s living standards. In fragile contexts, such stress can be a catalyst for conflict rather than a trigger event.

The pathways to violent conflict are no longer shaped by geopolitics alone.

Political fragility, social stress, economic confrontation, and ecological breakdown are interlocking forces that now push societies closer to instability, unrest and war.

As the Global Peace Index 2025 (GPI) and Ecological Threat Report 2025 (ETR) from the Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) show, peace is being eroded not just traditional military conflict, but by the failure to manage shared economic and environmental challenges, from inflation-driven hardship to water scarcity, food risk and climatic extremes.

The GPI, the world’s leading measurement of peacefulness, reports a continued decline in global peacefulness, with many indicators that herald conflict at their highest levels since the end of World War II. The report attributes this deterioration to rising geopolitical tensions, increased militarisation, domestic insecurity, and structural economic fragility that weighs heavily on social cohesion.

In 2025, the number of active state-based conflicts stood at its highest level in decades, and conflicts were increasingly complex, internationalised and intertwined with economic stresses. Societies with weakening institutions and growing economic fractures are more vulnerable to political breakdown, radicalisation, and violent dissent.

While economic pressures are now seen as an immediate threat, the ETR reinforces how ecological risks like water scarcity, food insecurity, extreme natural events and demographic pressures are rising in both frequency and intensity. These risks don’t just undermine livelihoods and human wellbeing, they magnify social tensions, weaken governance and erode resilience against conflict.

The ETR found that areas experiencing more extreme wet and dry seasons, signifying shifts in rainfall patterns, drought and flood risk, also show significantly higher rates of conflict-related deaths. This highlights how environmental volatility can interact with existing political and social stressors to heighten the risk of violence and instability.

The connection between ecological stress and social upheaval can be seen in the early 2026 protests in Iran. “Day Zero” water shortages, where major cities’ water systems are close to collapse, have become a flashpoint for mass discontent, along with economic factors including inflation and a weakening currency. Decades of drought compounded by climate change, unsustainable water extraction and mismanagement have left reservoirs dangerously low. Protests that might have begun over economic and political grievances have been fuelled in part by deep ecological stress as people see their basic rights to water and life jeopardised.

Iran is the latest example of how ecological breakdowns can rapidly become political and social crises when governance mechanisms fail to adapt or respond, a situation increasingly likely in many parts of the world as climate change intensifies. It also emphasises the broad spectrum of conflict risk: not just interstate war, but dissent, protest movements and systemic instability.

The emerging reality is one of compound risk.

Economic confrontation can weaken societies, making citizens more sensitive to grievances; ecological stress can further erode food and water security; and political fragility reduces the capacity to cope with shocks. When these threats intersect, they multiply.

An economy under strain may cut public services, decreasing social safety nets and raising unemployment. Simultaneously, drought or flood can devastate agricultural output, pushing food prices higher and deepening public anxiety. Without resilient institutions or robust governance, such combined stressors can contribute to social fragmentation, heightening the risk of violence, protests, or even civil breakdown.

The evidence from IEP’s research underscores that peace is not merely the absence of war. Positive Peace – the set of attitudes, institutions and structures that sustain peaceful societies – is equally about economic stability, social cohesion, and ecological resilience. Building that peace requires integrated strategies: promoting economic cooperation, strengthening social safety nets, investing in sustainable resource management, and bolstering institutions that can absorb shocks without breaking.

Ecological and economic threats feed into political instability and social unrest. Without holistic approaches that consider these interdependencies, the world will continue seeing conflict as a symptom of deeper unresolved systemic risks.