After nearly a decade of civil conflict that followed the 2011 overthrow of long-time ruler Muammar Ghaddafi, Libya has recently experienced a notable improvement in peacefulness. Since 2020, it has registered the largest improvement of any country in the Global Peace Index (GPI), improving by 25 places in the global rankings.

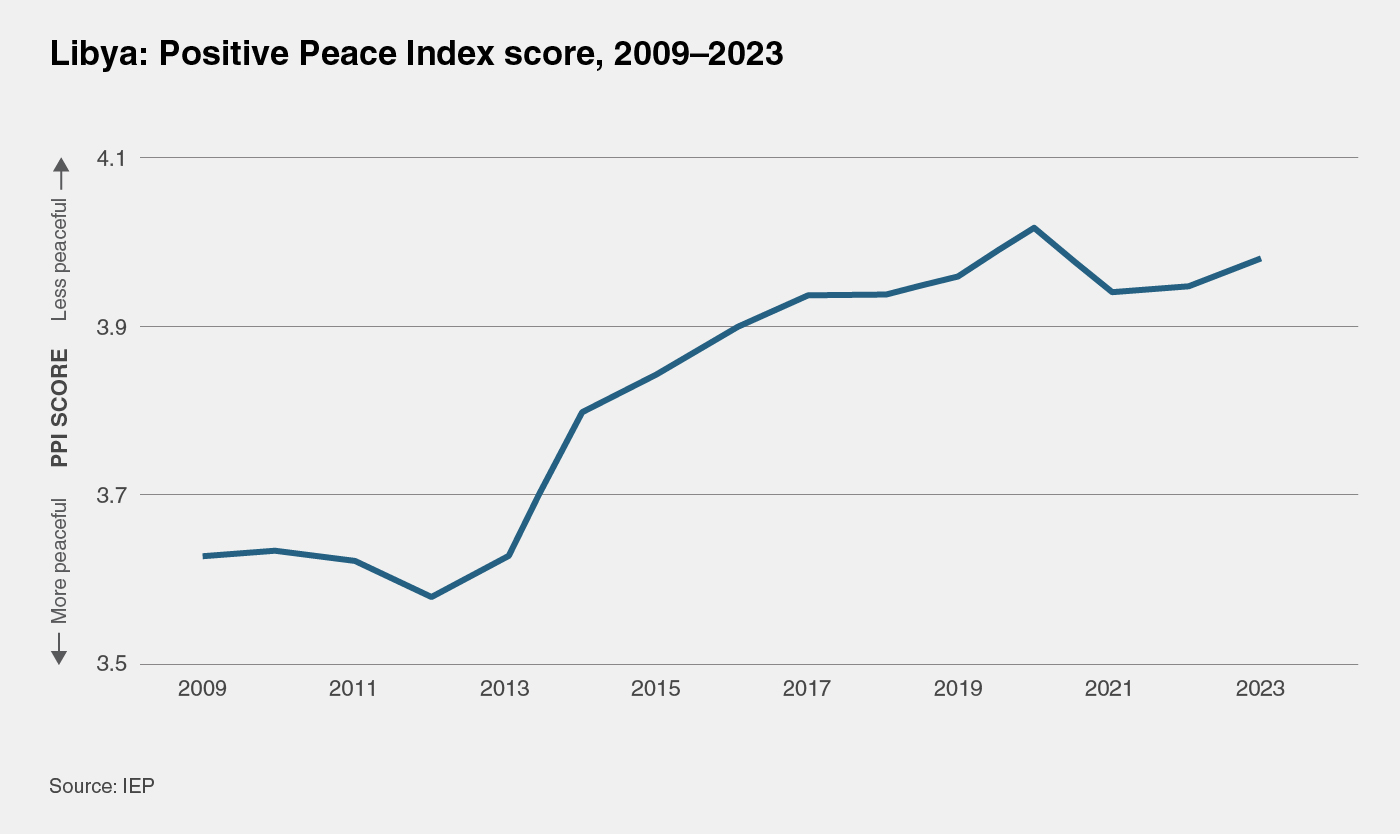

Yet Libya’s progress in reducing outward manifestations of violence belies the country’s extreme social fragility amid its deeply fractured military and political landscape. This fragility is reflected in Libya’s ongoing deteriorations in Positive Peace, IEP’s measure of social and institutional resilience. While Libya’s recent reductions in violence are welcome, they have come as the result of an untenable socio-political stalemate. Unless Libya’s fractures can be overcome and its institutional resilience can be strengthened, peace will remain unsustainable, as shown in the outbreaks of violence earlier this year.

Libya’s present-day instability is deeply rooted in the legacy of Gaddafi’s four-decade rule. Coming to power in 1969 through a military coup, Gaddafi established an authoritarian regime that dismantled formal institutions. His jamāhīriyyah system replaced traditional government structures with a complex network of people’s committees and revolutionary councils. Political dissent was harshly repressed, and opposition groups were exiled. While Gaddafi used oil wealth to fund social programs and infrastructure, his rule left Libya without functioning political institutions or a clear succession plan.

In the context of the Arab Spring, civil war broke out in the country in 2011, causing tens of thousands of deaths and leading to the regime’s collapse. This created a major power vacuum, in which militias, tribes and rival political factions competed for control.

Without strong institutions or a unified national army, Libya struggled to transition to democratic governance. Elections in 2012 initially brought hope, but growing tensions between Islamist and secular factions, along with the rise of powerful militias, led to renewed violence. This fragmentation triggered a second civil war in 2014, with frequent clashes and the involvement of external actors costing thousands more Libyan lives.

After six years of intensive fighting, this second civil war ended through a ceasefire agreement in 2020. These successive conflicts of the 2010s, combined with a substantial upsurge in terrorist activity, drove the massive deterioration in the country’s peace score, and their cessation has driven its subsequent improvement. The records of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, for example, count around 4,000 deaths from internal conflict in 2011. And from 2012 to the end of the decade, the country averaged more than 1,100 conflict fatalities per year, but it has recorded fewer than 15 conflict deaths each year since 2021. (It should be noted that all of these figures are considered conservative, as they exclude unverified or estimated fatalities.)

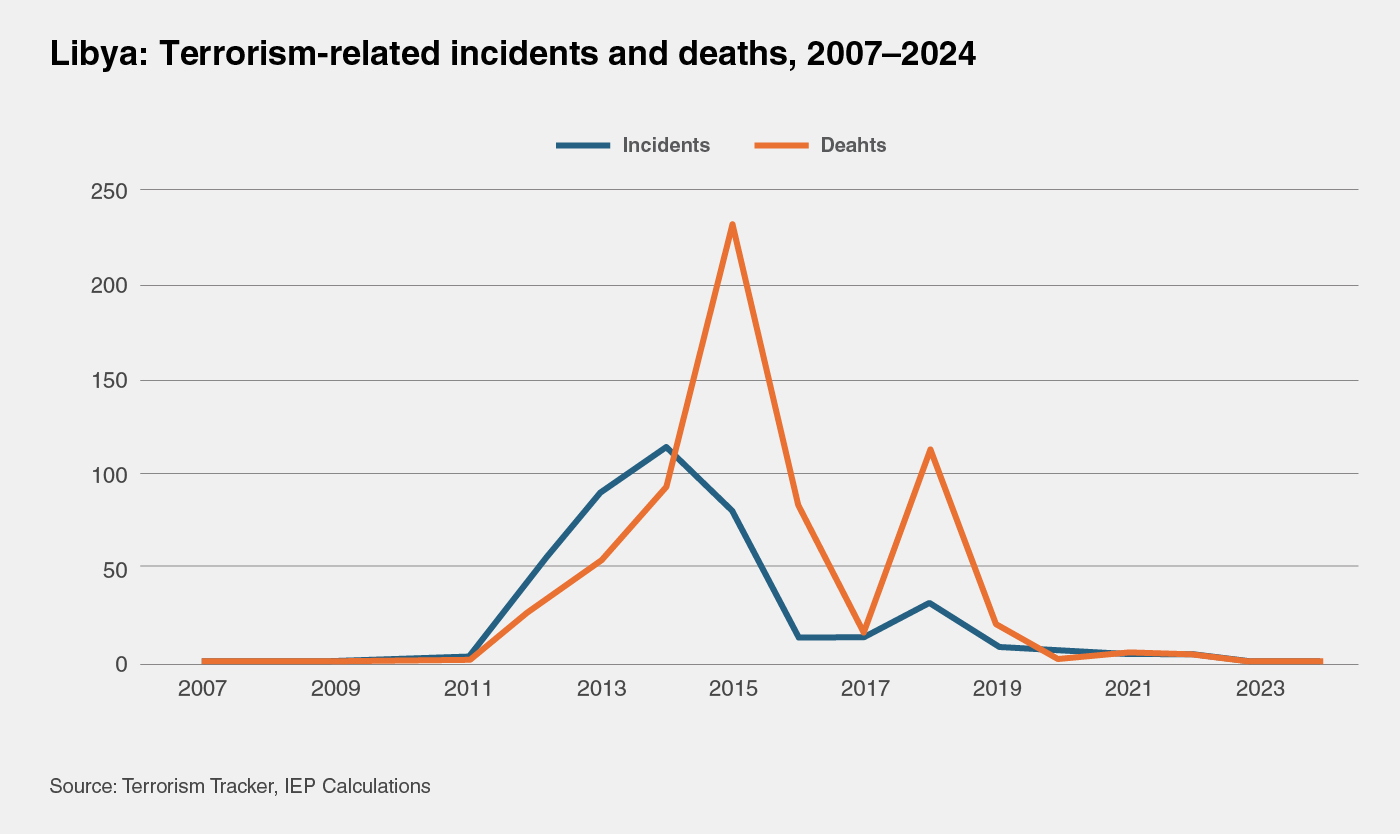

Similarly, according to the Global Terrorism Index 2025, terrorism peaked in Libya in the mid-2010s. There was a high of 234 terrorism-related deaths in the country in 2015. But there have been no recorded terrorist attacks or deaths since 2022.

While negative peace, defined as the absence of violence or fear of violence, has recently improved in Libya, this trend has not been accompanied by corresponding gains in Positive Peace. Positive Peace encompasses the social systems, institutions and governance structures that support long-term stability. By this metric, Libya has been on a largely consistent deteriorating trajectory for more than a decade. As of 2024, it ranks 145th out of the 163 countries in the Positive Peace Index (PPI).

Libya’s dearth of Positive Peace has been reflected in, and exacerbated by, the country’s fractured political landscape. In recent years, it has effectively been ruled by two governments, each controlling a large portion of its territory. The internationally recognised Government of National Unity (GNU) is based in Tripoli and controls the western part of the country, while a rival authority backed by Commander Khalifa Haftar controls Benghazi and the eastern part of the country.

Both factions claim legitimacy, but neither has been able to carry out the long-promised national elections, originally scheduled for December 2021. This stalemate has frozen reform efforts and left much of the country in a state of political uncertainty. Unless meaningful steps toward unity are taken, this persistent fragmentation of governance will leave the country vulnerable to renewed eruption of violence.

In early May 2025, for example, Tripoli experienced its most severe outbreak of violence in over a year, following the assassination of Abdel Ghani al-Kikli, a commander affiliated with the Government of National Unity. His death triggered armed clashes between government-affiliated forces and non-state actors. The violence quickly escalated in densely populated neighbourhoods, resulting in the deaths of both combatants and civilians. Although a UN-brokered ceasefire was reached by mid-May, the incident revealed the fragile nature of Libya’s security landscape.

Since that ceasefire, militia mobilisations have continued, particularly around Tripoli. These movements have prompted the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) to issue repeated warnings, most recently in July. While the overall conflict intensity has declined, the risk of future violence remains high.

Foreign involvement has further complicated this picture. Türkiye backs the GNU, while Russia, through proxies and private military contractors, supports Haftar’s forces. Though these powers may bring temporary stability to certain regions, they also obstruct national reconciliation.

Libya’s post-2011 trajectory reflects the gap between the absence of war and the presence of peace. While the country has moved beyond the peak of open conflict, the underlying drivers of instability – fragmented governance, foreign interference, and institutional collapse – remain in place. As a result, gains in peacefulness may prove temporary without deeper structural reforms and a resolution to the political and military deadlock.