For the past 50 years, Brazil’s management of the Amazon rainforest has been on a rollercoaster between development and preservation, with impact on not just Brazil’s environmental health, but also the global climate.

In the wake of the 1964 coup, Brazil’s military government adopted a stark motto for the Amazon: “Integrar para não entregar”- integrate so as not to hand it over. To the generals, the rainforest was a strategic frontier vulnerable to foreign encroachment. Their response was a series of colossal projects designed to cement sovereignty through occupation. The Trans-Amazonian Highway, launched in 1972, cut a path through dense forest, spawning feeder roads and settlement schemes. Federal development agencies such as SUDAM provided tax breaks, credit and subsidies to cattle ranchers and mining companies willing to establish operations in the basin.

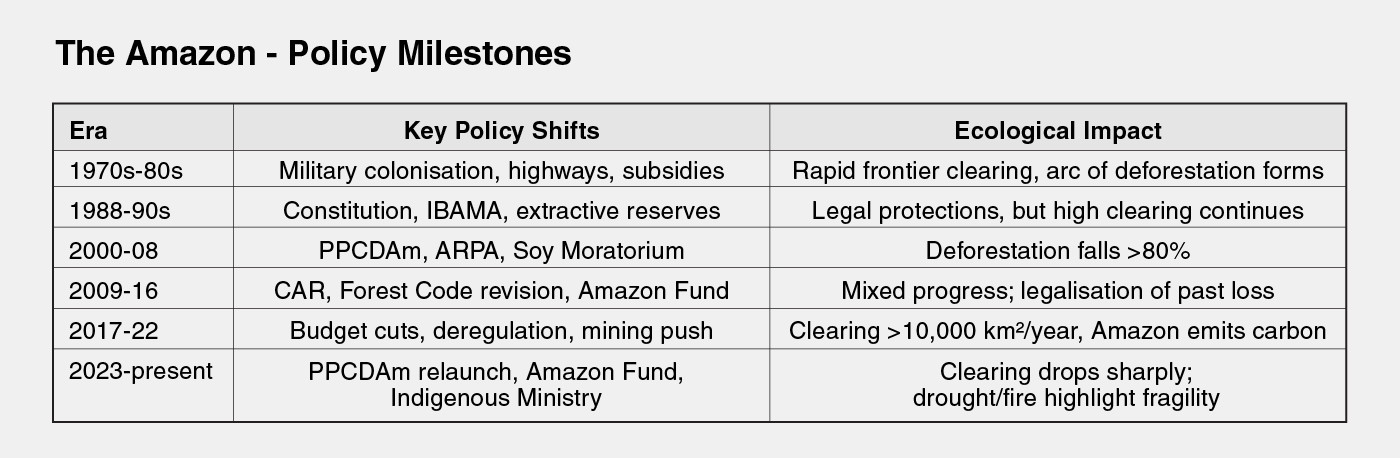

The ecological impacts were immediate. In the 1970s and 1980s annual deforestation increased; colonists were encouraged to clear land to prove productive use. The “arc of deforestation” formed along the southern and eastern fringes of the rainforest, which remain hotspots of forest loss to this day. Cattle ranching, incentivised by government credit and land-titling rules, became the dominant driver of clearing. Mining camps proliferated, leaving mercury-laden waterways and scarred landscapes.

Globally, these decades placed the Amazon on the environmental map as deforestation became a focus for international conservation movements. Yet domestically the forest was cast as an obstacle to development, and policies overwhelmingly favoured exploitation.

The 1988 Constitution enshrined environmental protection as a right of citizens and a duty of the state. It also recognised Indigenous land rights, mandating the demarcation of traditional territories. IBAMA was created in 1989 to consolidate enforcement. The assassination of rubber tapper and activist Chico Mendes that same year crystallised global anger and gave birth to the concept of extractive reserves.

This was a policy pivot: the forest was no longer an empty frontier but a socio-ecological system with citizens’ rights at stake. Enforcement, however, lagged. The 1990s still saw high clearing rates. But the legal scaffolding for future governance had been erected.

The early 2000s marked a decisive turn. The National System of Conservation Units (SNUC, 2000) laid out a framework for protected areas; the Amazon Region Protected Areas Program (ARPA, 2002) scaled conservation with donor backing.

In 2004, Brazil launched the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon (PPCDAm). Coupling satellite monitoring with “blacklists” and credit restrictions, it allowed real-time enforcement. The 2006 Soy Moratorium, brokered with agribusiness, prohibited soy sourcing from newly deforested Amazonian land.

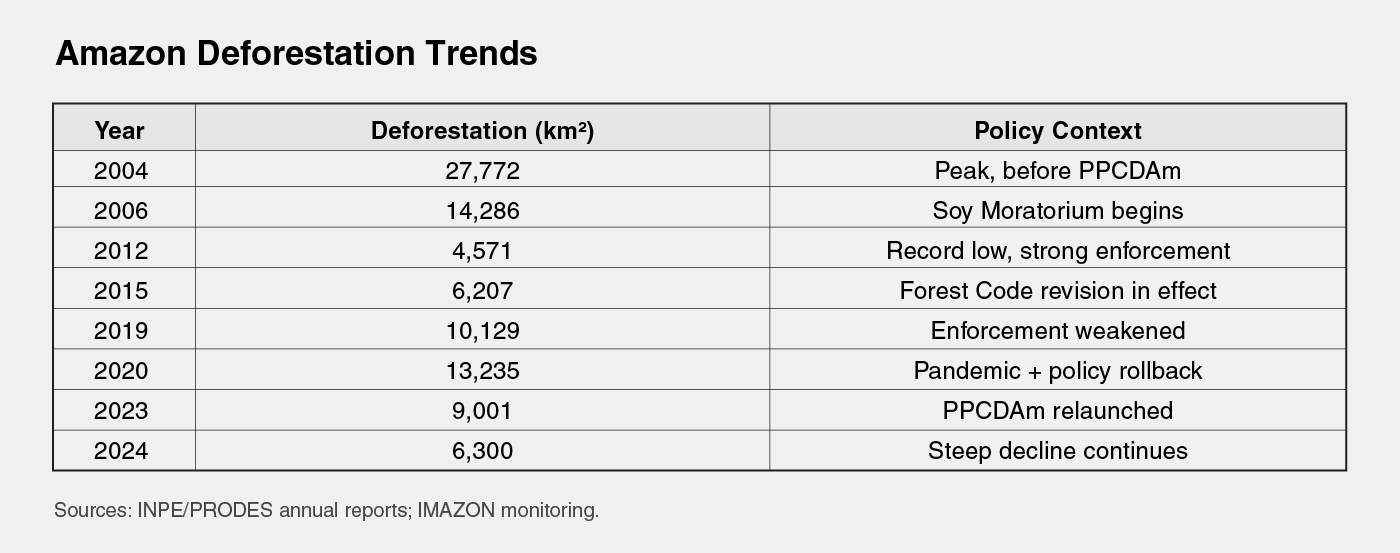

The results were dramatic: deforestation plummeted from 27,772 km² in 2004 to 4,571 km² in 2012. Brazil was hailed as the world’s leader in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, not by smokestack regulation, but by forest protection.

Brazil sought to embed gains in law. The Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) mandated digital land-use records. The 2012 Forest Code revision reaffirmed reserve requirements but controversially granted amnesties.

Deforestation remained relatively low by historic standards but fluctuated with commodity prices. Internationally, Brazil launched the Amazon Fund (2008), which channelled billions from Norway and Germany in results-based payments. Ecologically, the forest’s decline slowed, but degradation via logging, edge effects and fires continued to eat away at resilience.

Budget cuts and political headwinds eroded enforcement from 2016 onwards. Under the administration inaugurated in 2019, environmental agencies were defunded and politically constrained. Proposals to open Indigenous territories to mining gained momentum.

Annual clearing returned to five-figure levels, with 2020 registering over 13,000 km². Fires escalated, often deliberately set to clear newly cut land. The Amazon’s role as a carbon sink weakened; studies showed parts of the eastern basin now emit more carbon than they absorb.

A policy reversal followed the 2022 election. PPCDAm was relaunched, the Amazon Fund reactivated, and a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples established. Large-scale raids targeted illegal mining in Yanomami lands. By 2023–24 deforestation fell by about half compared to 2022.

Yet ecological alarms continue. The Amazon experienced a record drought in 2023, underlining that climate change and forest degradation may push the system towards a tipping point if 20-25 per cent of cover is lost.

The wider Amazon basin has become increasingly vulnerable to prolonged droughts and large-scale wildfires, with 2023 and 2024 marking the hottest years on record. The 2025 Ecological Threat Report (ETR) found this contributed to Western Brazil recording some of the world’s sharpest increases in ecological threat levels.

As COP30 convenes in Belém, the question is whether the current revival of enforcement and finance can endure long enough to anchor a lasting bio-economy for the region, or whether political cycles will continue to swing the Amazon between protection and peril.

References